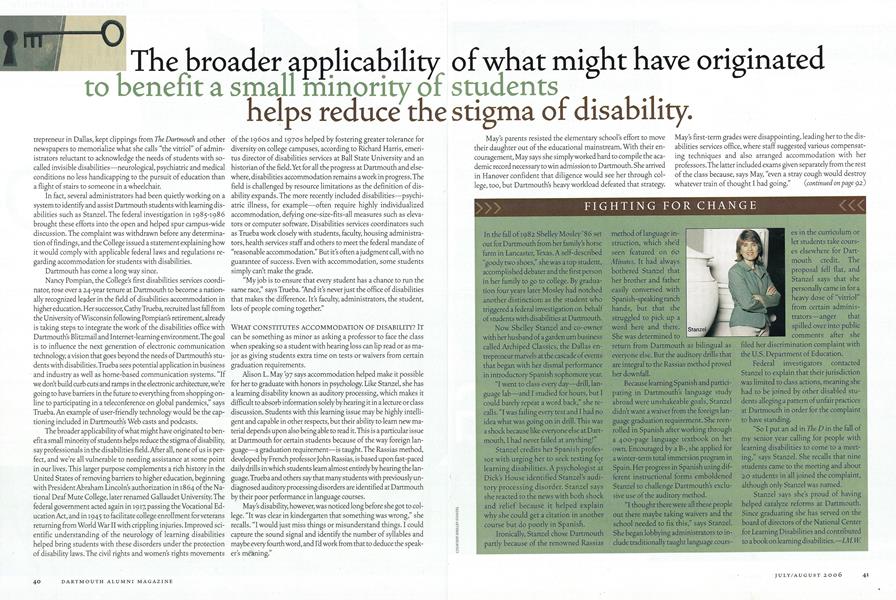

In the fall of 1982 Shelley Mosley '86 set out for Dartmouth froni her family's horse farm in Lancaster, Texas. A self-described "goody two shoes," she-was a top student, accomplished debater and the first person in her family to go to college. By graduation four years later Mosley had notched another distinction: as the student who triggered a federal investigation on behalf of students with disabilities at Dartmouth.

Now Shelley Stanzel and co-owner with her husband of a garden urn business called Archiped Classics, the Dallas entrepreneur marvels at the cascade of events that began with her dismal performance in introductory Spanish sophomore year.

"I went to class every day—drill, language lab—and I studied for hours, but I could barely repeat a word back," she recalls. "I was failing ever)- test and I had no idea what was going on in drill. This was a shock because like even-one else at Dartmouth, I had never failed at anything!"

Stanzel credits her Spanish professor with urging her to seek testing for learning disabilities. A psychologist at Dick's House identified Stanzel's auditory processing disorder. Stanzel says she reacted to the news with both shock and relief because it helped "'explain why she could get a citation in another course but do poorly in Spanish.

Ironically, Stanzel chose Dartmouth partly because of the renowned Rassias method of language instruction, which she'd seen featured on 60Minutes. It had always bothered Stanzel that her brother and lather easily conversed with Spanish-speaking ranch hands, but that she struggled to pick up a word here and there. She was determined to return from Dartmouth as bilingual as everyone else. But the auditory drills that are integral to the Rassias method proved her downfall.

Because learning Spanish and participating in Dartmouth's language study abroad were unshakeable goals, Stanzel didn't want a waiver from the foreign language graduation requirement. She reenrolled in Spanish after working through a 400-page language textbook on her own. Encouraged by a B-, she applied for a winter-term total immersionprogram in Spain. Her progress in Spanish using different instructional forms emboldened Stanzel to challenge Dartmouth's exclustansive use of the auditory method.

out there maybe taking waivers and the school needed to fix this," says Stanzei. She began lobbying administrators to include traditionally taught language courses in the curriculum or let students take courses elsewhere for Dartmouth credit. The proposal fell flat, and Stanzel says that she personally came in for a heavy dose of "vitriol" from certain administrators-anger that spilled over into public after she filed her discrimination complaint with the U.S. Department of Education.

Federal investigators contacted Stanzel to explain that their jurisdiction was limited to class actions, meaning she had to be joined by other disabled students alleging a pattern of unfair practices at Dartmouth in order for the complaint to have standing.

Stanzel says she's proud of haying helped catalyze reforms at Dartmouth. Since graduating she has served on the board of directors of the National Center for Learning Disabilities and contributed to a Book on learning disabilities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July | August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

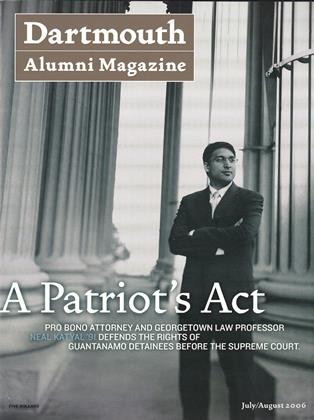

Cover Story

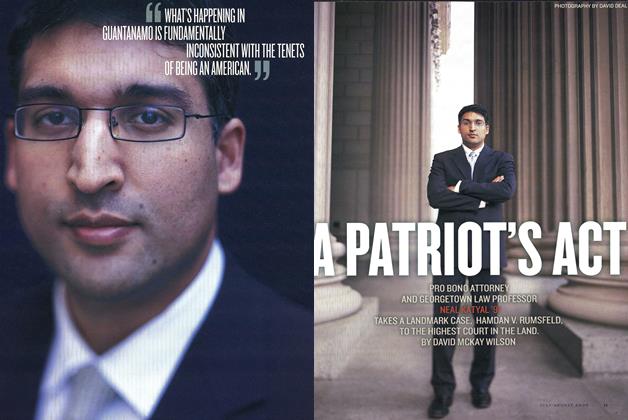

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July | August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

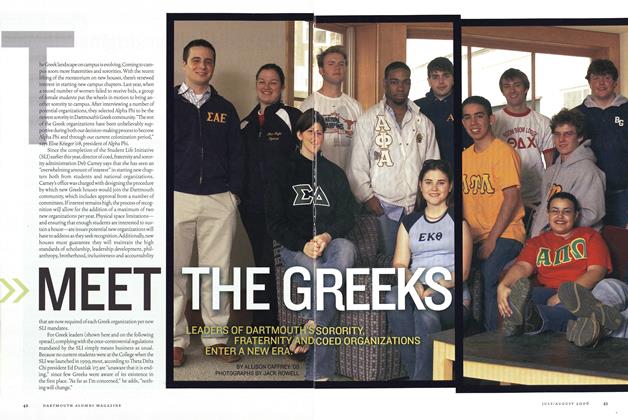

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02