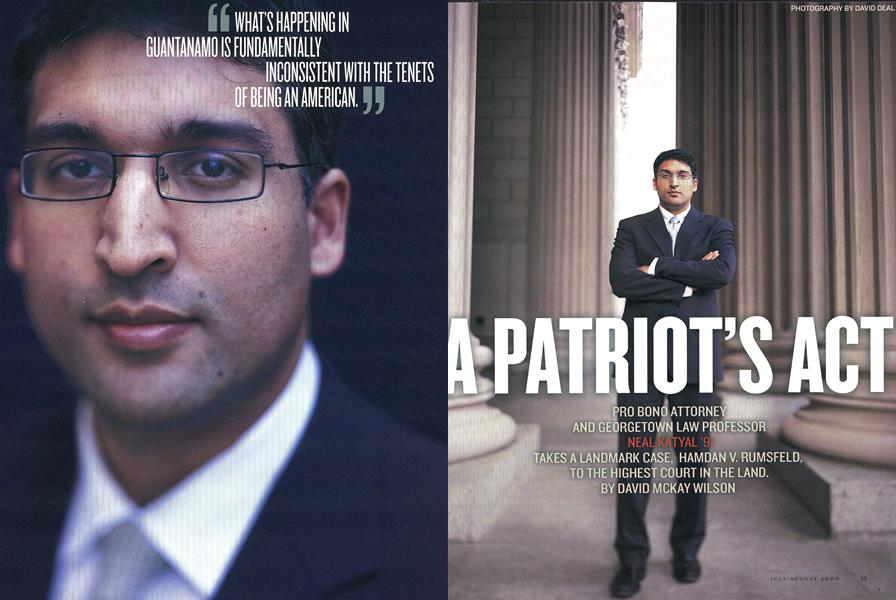

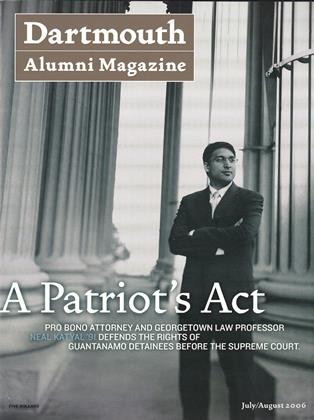

A Patriot’s Act

Pro bono attorney and Georgetown law professor Neal Katyal ’91 takes a landmark case, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, to the highest court in the land.

July/August 2006 DAVID MCKAY WILSONPro bono attorney and Georgetown law professor Neal Katyal ’91 takes a landmark case, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, to the highest court in the land.

July/August 2006 DAVID MCKAY WILSONPRO BONO ATTORNEYAND GEORGETOWN LAW PROFESSOR NEAL KATYAL '91 TAKES A LANDMARK CASE, HAMDAN V. RUMSFELD,TO THE HIGHEST COURT IN THE LAND.

As lead attorney in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, a landmark battle over presidential and congressional power, Katyal is working around the clock on this mid-February day as his oral argument draws nigh before the nations highest court. It will be his first argument before the court, so he is taking no chances.

He pulls an all-nighter to make the deadline for an emergency brief, then arrives the next morning, unshaven, to teach his seminar on "The Law of Terrorism" in a Georgetown University Law Center classroom, which has aview of the U.S. Capitol a few blocks away. The John Carroll Professor of Law seems weary. But he is also satisfied he'd done his best for Salim Hamdan, the Yemeni apprehended in Afghanistan in 2001 and detained at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba for more than four years.

In a case with many twists, Hamdan's latest is a doozy: The U.S. government argues the Supreme Court has no right to rule on the case, citing recent,congressional action that deprived Guantanamo detainees access to federal courts.

"It has been a rough 48 hours," Katyal, 36, tells students sitting behind desks arrayed in a circle, their laptops plugged in for note-taking. "Can Congress pass a vague law to remove a case from the Supreme Court docket? I think the answer is no, but the government thinks otherwise."

The case has vaulted Katyal into prominence on an issue at the heart of the debate over the Bush administrations post-9/11 national security strategy. At a time when the president has asserted broad executive powers during the "War on Terror," Katyal has challenged Bush's authority to set up military commissions to try Hamdan, one of the 558 so-called enemy combatants detained at Guantanamo.

By March Katyal had spent at least 5,000 pro bono hours on the case—equal to more than two years in a 40-hour-a-week job arguing that the commissions violate the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the Geneva Convention and the U.S. Constitution. He maintains Bush should have sought congressional approval to set them up, and that the commissions violate the U.S. Constitutions equal protection clause because they will handle only the cases of non-citizens. In addition, Hamdan was charged with conspiracy, which Katyal argued is not considered an international war crime. The ruling is expected by July 1.

The case has personal meaning for Katyal, whose parents immigrated to Chicago from India the year before he was born. Katyal recalls the day he met Hamdan at Guantanamo. By then, Hamdan had been incarcerated for three years. Katyal feared his client would lash out over his continued incarceration. Instead, Hamdan wanted to know why his lawyer had devoted so much time to his case.

"I said that my parents had come from India. They thought America was a place where people were treated equally and their kids would have an amazing life," Katyal told law students at a 2005 panel at American University. "What's happening in Guantanamo is fundamentally inconsistent with the tenets of being an American. These are the first military trials to single out foreigners. We are supposed to have equal protection under the law."

His critique of the Bush administrations anti-terror tactics extends beyond Guantanamo. A day after submitting his emergency brief, Katyal appears on CNN debating the National Security Agency's domestic wiretapping program with congressional leaders and former administration officials. While the Bush allies argue that Congress approved the program by authorizing the use of force following the 9/11 attacks, Katyal maintains that the president violated U.S. law by tapping phones without a warrant.

The attorneys work has caught the eye of national legal experts. The National Law Journal in 2005 named Katyal one of the leading "40 Lawyers under 40" and winner of its pro bono advocacy award for his Guantanamo work.

"I am so impressed by the swiftness and subtlety of Neal's mind," says attorney David Remes, who is assisting Katyal on Hamdan. "He's book-smart, intellectually creative and a very good organizer of talent. This is a field with lots of big egos, and he's pretty good at managing this herd of cats."

Katyal's volunteer legal team includes 19 lawstudents from Yale, Harvard, Georgetown and Michigan, as well as a disparate coalition of attorneys who wrote 37 amicus briefs for the case—including Remes, members of the conservative Cato Institute and the left-leaning Center for Constitutional Rights, and several retired generals and admirals.

The private bar and academia are a crucial part of Katyal's high powered network. This winter he practiced his oral argument at 11 moot courts at several law schools and before private attorneys from Seattle to Washington, D.C. In these sessions he responded to the rapid-fire questioning expected from the Supreme Court justices, especially the conservative jurists who may be skeptical of his arguments. Katyal and his team had devised a list of 500 questions the justices might ask.

When he came to Harvard Law School for a moot court in early March Katyal invited Kenneth Strange, director of the Dartmouth Forensic Union (the debate team), to observe while several Harvard legal luminaries grilled him. Strange coached Katyal during his four years on the Colleges debate team. "The people playing the role of the justices kept cutting him off in the middle of his argument and were really going after him," says Strange. "Neal was exceptional as he adjusted to the constant interruptions. He barely had time for his argument."

The practice sessions did little to calm Katyal. "For the three weeks before the argument I was nervous almost every minute of every day," he says.

At the March 28 hearing before the Supreme Court, which was expanded 3 o minutes beyond the normal hour-long session, Katyal reined in those nerves. "When I got to the podium, within a half minute, my nervousness subsided and I just wanted to have a conversation with them," he says. Five justices appeared skeptical of the administrations argument that Congress had removed the case from the courts jurisdiction by denying Guantanamo detainees access to federal courts. Less certain was whether Katyal would woo a majority to find the tribunals unconstitutional—and toss out Hamdan's conspiracy charge.

"What you can't do is use the stand-alone charge of conspiracy," Katyal told the court. "It's too vague. The world rejects conspiracy because it would allow too many individuals to get swept up in its net."

His "conversation" at the Supreme Court came 20 years after Katyal first met Strange at the Dartmouth Debate Institute, a month-long summer program for top-notch teen debaters.

It was an intellectually stimulating summer for Katyal, then between his junior and senior years at Loyola Academy in Chicago. He felt so at home at the debating society in Hanover that he decided to make Dartmouth his top choice. A year later he began competing for Dartmouth on the intercollegiate circuit that takes students to weekend matches around the country.

He recalls one debate in which the question involved the rights of foreigners apprehended by American authorities outside the United bateStates. The same issue lies at the center of Hamdan. "Its very wild," says Katyal, who was a guest speaker at the 2005 Dartmouth Debate Institute. "Fifteen years ago I was debating this issue among college students. Now I'm arguing it at the Supreme Court."

While Hamdan was Katyal's first oral argument before the Supreme Court, it wasn't his first involvement in high-profile cases decided there. He collaborated in 2002 with conservative legal scholar Richard Epstein in a brief that outlined how the Supreme Court could avoid ruling on the merits of the explosive case involving a young girl's challenge to reciting the "Pledge of Allegiance" in school. A lower court found that the pledges "under God" clause violated the separation of church and state.

Katyal and Epstein showed the Supreme Court there were too many unsettled issues in California state law to make it a suitable case to decide such a momentous question. It turned out the girls father wasn't married to her mother, which, Katyal and Epstein argued, clouded the fathers standing to bring the lawsuit on her behalf. The court agreed.

A year earlier Katyal had written a brief for law school deans across the nation who backed affirmative action at the University of Michigan Law School. The court ruled in the deans' favor.

In 2000 he was co-counsel in Bush v. Gore, which settled the contested presidential election. He was on Gore's legal team, which lost when the court rejected the argument that the Florida elections board—not the U.S. Supreme Court—should decide who won the states electoral votes. During those tumultuous five weeks he worked alongside Harvard Law professor Lawrence Tribe and headed up a team of 10 Yale law students and several lawyers from around the country. Over 36 days the case went to the Supreme Court twice.

As he prepared for Hamdan, Katyal took a look back at the brief he co-authored in the Gore case, which was decided for Bush in a 5-4 ruling. The outcome, Katyal says, upset him greatly because he thinks the decision should have been made in Florida. "I believe in a very limited role for federal courts," he says, noting that his students often tease him for being too deferential to elected officials. "Our position squared with my strong belief that courts should stay out of the process, absent the most compelling of circumstances. It didn't seem to be then, and still does not, that the federal Constitution somehow justified the intervention of the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2000 election."

Among those impressed by Katyal during the presidential fight was Tribe, who later helped him on Hamdan.

"In 2000 Neal stood out as one of the most imaginative of the many young attorneys and teachers who were eager to assist," says Tribe. "How he will fare in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld is, of course, uncertain, but that he has shown great courage and resourceful ness in the face of tremendously uphill odds is beyond doubt."

Katyal's path to the Supreme Court began at Dartmouth, where professors encouraged his intellectual curiosity and taught him how to focus it through scholarly research. He pursued a government major, modified by Asian studies. By senior year he'd decided upon a career in academia but didn't know what field to pursue. After graduation he stayed in Hanover, working as assistant coach of Dartmouth's debate team while reading extensively on economics and literary criticism, two subjects he'd wanted to study during his undergraduate years.

He finally settled on law. He began his studies at Yale Law School then quickly decided he'd one day teach law. He liked the fact that law schools were mostly located in cities and that the publishing demands for tenure were less than for a university pro- fessorship. "You have to write a few articles, but I liked the idea of not having so much pressure," says Katyal, who lives in Washington, D.C., with his family. "I like doing scholarship for its own sake. I work better with internal deadlines, rather than external ones."

He took the traditional career path to become a law professor. He served as a clerk in 1995-1996 for U.S. Appeals Court Judge Guido Calabresi, the former Yale Law School dean. The next year he clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, who was on the bench March 28 listening to Katyal's argument on Hamdan.

He won an appointment to teach at Georgetown, but that was postponed for two years after he was asked to join the U.S. Justice Department in 1997. There he worked as a national security advisor and wrote a report for President Clinton on the need for more pro bono legal assistance by private lawyers.

In 1999 he began teaching fulltime at Georgetown. Publishing, it turns out, wasn't a problem for Katyal, a prolific writer who had 10 articles in prestigious law publications by 2000. Several focus on computer crime, while others look at the need to shift to a model of crime prevention instead of prosecution.

In the fall of 2001 Katyal was back at Yale as a visiting professor at the law school. His newborn son kept him up the night of September 10, and when his wife awakened him the next morning with the horrific news from Manhattan, Katyal, who worked on terrorism issues at the Justice Department, thought at once that bin Laden was involved.

Two months later Bush issued the order that set up the military tribunals. Katyal recalls reading about Bush's order in The NewYorkTimes over breakfast. He dug up the source document on the Internet and quickly decided that Bush's initiative had usurped congressional powers.

Two days later he told his constitutional law students about his discovery. "I walked into class and said I'd found something blatantly unconstitutional," he says.

Katyal dove headlong into the research. In two weeks he was before the Senate Judiciary Committee with a 25-page briefing paper detailing how Bush's order didn't jibe with the U.S. Constitution because Congress, not the president, had the power to establish tribunals.

"A tremendous danger exists if the power is left in one individual to put aside our constitutional traditions and protections when he decides the nation is in a time of crisis," wrote Katyal. "The safeguard against the potential for the abuse of military trials has always been Congress' involvement."

By 2002 his views were fine-tuned in a Yale Law Journal article co-written with Tribe. That piece caught the eye of Navy Lt. Cmdr. Charles Swift, who'd been appointed to defend Hamdan, and he decided to contact Katyal. Helping Swift represent Hamdan wasn't popular, even at home. Katyal says it ruined Thanksgiving dinner in 2005 when he told his extended family about his latest client.

But the support he received from lawyers in the military justice system strengthened his determination to take this case to its ultimate conclusion. He also remembered the Justice Department report he wrote in 1999 encouraging attorneys to volunteer their skills to help those who can't afford representation.

"You needed a high-security clearance, which I had from working in the Justice Department, and you needed to understand international law, constitutional law and criminal law," Katyal says. "I happen to have that skill set. I knew it wouldn't be popular with everyone, but I felt I had an obligation to take the case."

As Katyal awaits the Supreme Court's decision, he has shunted aside pleas for assistance on other thorny constitutional legal battles. He has returned to his scholarly pursuits, which he says he can undertake without the unrelenting pressure of court deadlines. In fact, just three days before his oral argument, Katyal delivered a paper at Yale looking at the separation of powers in the U.S. government, arguing that rivalries within the executive branch could be encouraged as a check to presidential powers.

"It's time to do academic work for a while," he says. "I've always liked the idea of working at my own pace. It's not that I work less hard, it's that you get to set your own deadlines, and you can't do that in a court."

WHAT'S HAPPENING INGUANTANAMO IS FUNDAMENTALLYINCONSISTENT WITH THE TENETSOF BEING AN AMERICAN.

HAMDAN WANTED TO KNOW WHYHIS LAWYER HAD DEVOTED SO MUCH TIME TO HIS CASE."I SAID THAT MY PARENTS IAD COME FROM INDIA.THEY THOUGHT AMERICA WAS A PLACE WHERE PEOPEEWERE TREATED EQUALLY."

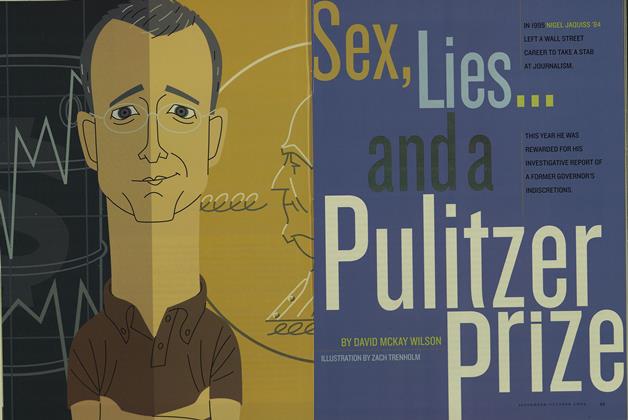

DAVID MCKAY WILSON, a New York-based journalist, wrote aboutjournalist Nigel Jaquiss '84 in the September/October 200$ issue of DAM.

LISTEN TONEAL KATYAL'SARGUMENT For,the past 51 years the U.S. Supreme Court has made audio recordings of its proceedings and given them to the National Archives at the end of each term. Since 2000 the court has allowed the immediate release of the recordings in 12 high profile cases of national interest. Constitutional scholar Neal Katyal has been involved in three of those cases. He was co-counsel for Vice President Ai Gore in Gore v. Bush, the first audio made available in 2000. In 2003 he co-authored an influential amicus brief in Grutter v. Bollinger, which involved affirmative action at the University of Michigan. Then came Katyal addressing the court in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld on March 28. To listen to the oral argument, go to www.law.georgetown.edu/webcast/assets/GL_2006331103740,mp3.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July | August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

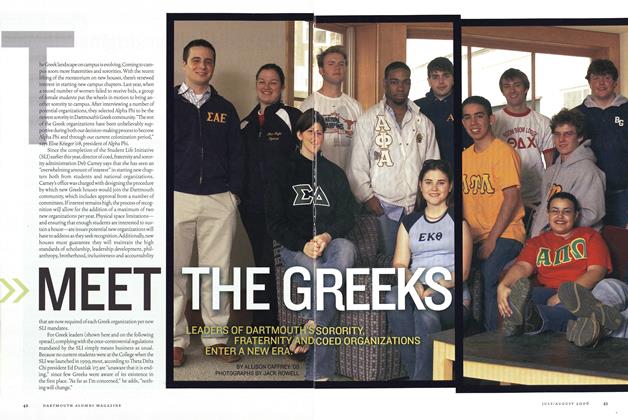

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July | August 2006 By Lucas Swaine

DAVID MCKAY WILSON

-

Feature

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Article

ArticleClass Of 1995

July/August 2007 By David McKay Wilson -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“A Huge Story”

Sept/Oct 2008 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDESea Change

Jan/Feb 2009 By David McKay Wilson -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

Jan/Feb 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

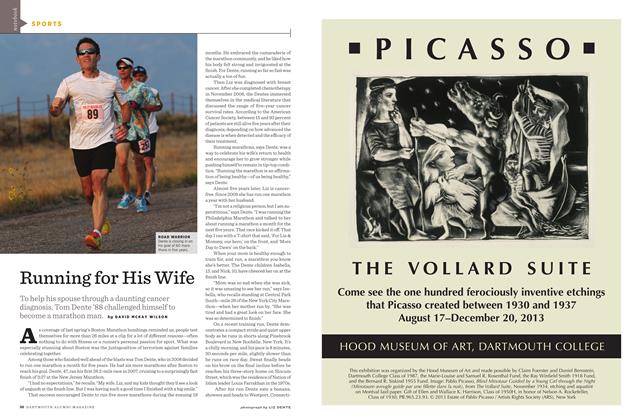

Sports

SportsRunning for His Wife

September | October 2013 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON