Aristotle on the A-Train

A teacher finds an appreciation of the classics in an unlikely place: a ninth-grade classroom in Brooklyn.

Nov/Dec 2007 Alexander Nazaryan ’02A teacher finds an appreciation of the classics in an unlikely place: a ninth-grade classroom in Brooklyn.

Nov/Dec 2007 Alexander Nazaryan ’02A teacher finds an appreciation of the classics in an unlikely place: a ninth-grade classroom in Brooklyn.

ODYSSEUS MAY HAVE LED THE Greeks to victory over Troy, blinded a Cyclops, spent 10 years sailing the Mediterranean in search of home and wife, and killed the suitors who had been devouring his kingdom, but he gets mixed reviews from my students at the Brooklyn Latin School. "By the way, I don't like Odysseus anymore," a ninth-grader announced in an e-mail, referring to an episode in which Homers hero chokes his beloved old nurse, threatening to kill her if she so much as whispers about his clandestine return to Ithaca.

In a similar vein, a student is writing an essay in which she pins Odysseus' misfortunes on his outsized machismo, while another is arguing that The Odyssey is absent of heroes altogether, since every character is "flawed and gods do all the dirty work anyway. A few are intent on defending the maligned warrior, but my students' reading of the epic is a far cry from the days when one assumed that Odysseus is a hero merely because he has a razor-sharp wit and enough bravura to make James Bond blush. While my students' approach to the epic strays from tradition, it fascinates me to watch them grapple with the text, struggling to square their own values with those of ancient Greece.

Although I now teach at a classical high school (the Brooklyn Latin School mandates four years of Latin, the only public school in New York City with that requirement, and all classes have a strong emphasis on the classics), my own journey to antiquity had its share of twists and turns. During my first three years at Dartmouth I categorized the classics along with prowling Safety & Security officers on Friday nights and bitter New Hampshire winds on Monday mornings—as something that could make my experience in Hanover very cumbersome indeed. Having declared an English major, I took it for granted that the difficulty of reading Homer, the cause of many a late night back in high school, was well behind me. It was through an independent study on modern sexuality, of all topics, that I discovered just how much the ancients still mattered.

Sitting within the snug confines of Sanborn House one evening, sinking into a leather chair after a second cup of tea, I read Michel Foucault's A History ofSexuality, a groundbreaking study of the varieties of sexual experience and the crie du coeur of a man who sought to ground the sexual-identity debate of the 1960s in a historical context that reaches all the way back to the ancient Greeks. They were neither sybarites nor staid philosophers, Foucault argues, but men who understood that the body is a source of pleasure—a temporary vessel, yes, but a fascinating one. This "practice of the self," as Foucault terms the unique self-awareness of the ancient Greeks, would inform the entirety of Western thought from Plato to Freud by introducing the idea of eros (love) in its dazzling variety. Some hours later when I finally left Sanborn, my head in a daze, I was completely hooked. When I found myself immersed in a thesis on postmodern theory in the following year I could not help seeing "the great loveliness of ghosts" (to borrow Homers term) behind the contemporary thinkers I was studying; Heraclitus, Socrates, Plato Aristotle and Lucretius lurking in the shadows of avant-garde theorists from Berkeley and the Sorbonne.

When the Brooklyn Latin School opened last year I gave hardly a second thought to leaving the middle school where I had begun my teaching career. New York's newest elite, specialized school—a constellation of eight schools for which students must take an entrance exam; roughly 5 percent of the 30,000 yearly applicants gain admission—the Brooklyn Latin School is modeled after Boston Latin, the oldest high school in the country and one that boasts Benjamin Franklin John Adams, Leonard Bernstein and innumerable Dartmouth men and women among its alumni. The Brooklyn Latin School was founded to replicate the venerable Boston Latin tradition but with a distinctively New York City flavor. Hailing from all over the city, enduring long rides on the subway from the upper reaches of the Bronx or suburban stretches of Staten Island, my students have some very basic things in common: They can conjugate a Latin verb, recite Homer from memory and evaluate the effects of Rome's spreading influence during the first century A.D.

the classics is the perpetuation of an historical outlook in which great men (dead and white, as a rule) do great things, while just about everyone else is consigned to oblivion. While this argument may have some visceral appeal, it usually dissipates in the face of instruction that strives for understanding beyond simplistic distinctions. The students who are riveted by The Odyssey or argue passionately about imperial Rome in Socratic seminars (another requirement of the school) truly represent the social, economic and ethnic patchwork quilt of New York City. Instead of dividing them, the classics give them a sense of unity, revealing how the ideas we grapple with today have their roots in antiquity, how the five boroughs of New York are not so different from the seven hills of Rome. They study Aristotle because his insights into human virtue inform the arguments about moral values gripping America do-day. Nightly images of the carnage in Iraq fuel discussions of Virgil's Aeneid, an unflinching portrait of a war that, much like our current campaign, began with A persistent argument against teach-decocratizing intentions.

Then again, in this age of Google and Black Berry, there are probably some who think we would better serve our students by handing them laptops instead of Latin textbooks and teaching them HTML instead of Homer, thereby preparing them for the reality of today's competitive workforce. While technological literacy is important, no computer has ever taught a student how to construct an effective argument (as Plato does in his dialogues) and no PowerPoint presentation will ever replace the majesty of effective public speaking (the domain of eminent Romans such as Horace and Cato). The lasting value of learning Latin, reading epic poetry and generally studying the classics is a rigor of thought at the highest level, a skill that our educational institutions all too often neglect.

I almost left Dartmouth without ever reading the classics; many do, never cracking a copy of Homers Iliad, so relevant to our age, or Sappho's love poems, deeply unsettling in their immediacy. The Brooklyn Latin School has given me an intellectual reprieve, allowing me to teach the works I've grown to love, so that when my students reach college they'll be able to speak intelligently on the Pax Romana (Roman peace) or debate the reasons for Plato's conservatism in his later works. And it's happening already. When we discuss TheOdyssey in class—is Odysseus a hero? is Penelope as faithful as she seems?—my students are in the presence of the same muses to which Homer once sang. The journey from Olympus to Brooklyn is not so long, after all.

The lasting value of learning Latin is a rigor of thought at the highest level.

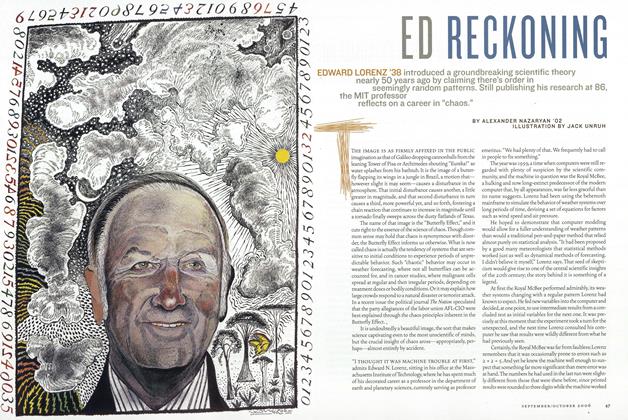

ALEXANDER NAZARYAN wrote a profile ofEd Lorenz '39 for the Sept/0ct 2006 issue of DAM and a story about Arctic explorer Vilh-jalmurStefanssonfor the last issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

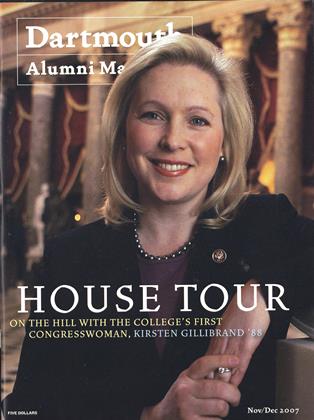

Cover Story

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

November | December 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureDrug Buster

November | December 2007 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

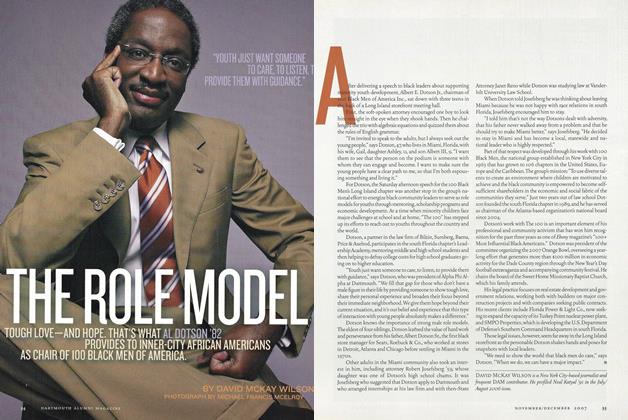

FeatureThe Role Model

November | December 2007 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97 -

ONLINE

ONLINENo Ordinary Joe

November | December 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91

Alexander Nazaryan ’02

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLove and Empire

July/August 2011 By Courtney Cook ’93 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClutch Situation

July/Aug 2013 By Daisy Alpert Florin ’95 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYNew Girl in Town

May/June 2012 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYDaily Lessons

May/June 2006 By Ken Roman ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July/August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYRoyal Treatment

Sept/Oct 2009 By Richard Hansen ’07