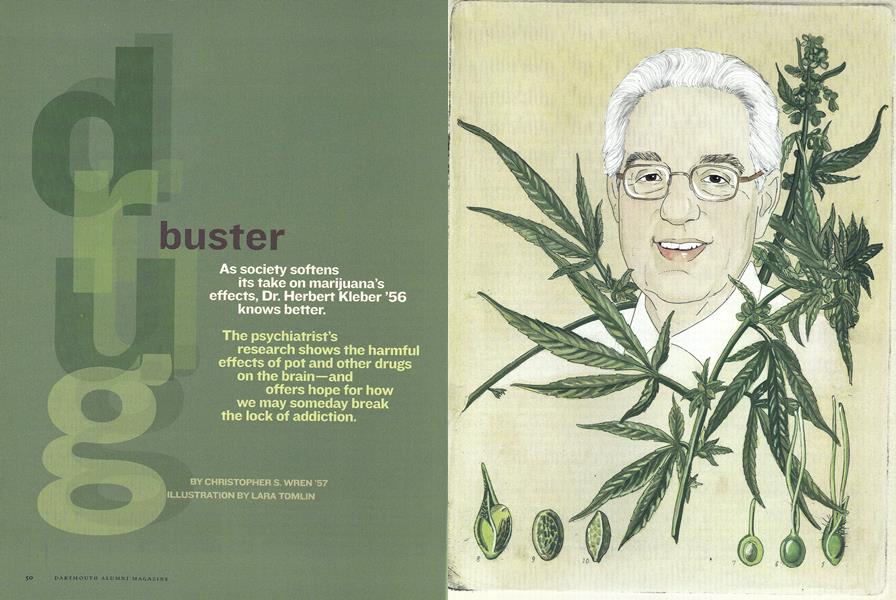

Drug Buster

As society softens its take on marijuana’s effects, Dr. Herbert Kleber ’56 knows better.

Nov/Dec 2007 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57As society softens its take on marijuana’s effects, Dr. Herbert Kleber ’56 knows better.

Nov/Dec 2007 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57As society softens its take on marijuana's effects, Dr. Herbert Kleber '56 knows better.

The psychiatrist's research shows the harmful effects of pot and other drugs on the brain—and offers hope for how we may someday break the lock of addiction.

Dr. Herbert D. Kleber '56 disagrees with the legendary Beatle. Medical professionals as well as the general public, he says, take marijuanas risks too lightly.

"Parents have tended to buy that line," Kleber told an audience of doctors and nurses at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center last year. "This is a much more potent drug than it was back in the 1960s or the 1970s."

Kleber's disapproval of pot is based not on his own use, though he tried it as a teenager, but on a career of meticulous research into the abuse of heroin, cocaine, marijuana and other illegal substances.

He served as deputy drug czar in the White House of President George H.W. Bush from 1989 to 1991. In 1995 he won the Nathan B. Eddy Award as the nations best scientific researcher into drug abuse. Now 72, Kleber still works full time as professor of psychiatry at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons and as director of a substance abuse division that he founded at the New York Psychiatric Institute. His name appears on lists of best doctors.

Anyone mistaking Kleber for a humorless puritan would be disarmed by his puckish wit and exuberance for a career spent sifting through the flotsam and jetsam of drug addiction. Like St. Jude, he is a passionate advocate for seemingly hopeless causes.

"I feel I've been given the greatest gift that God can give to a person Kleber says during an interview in his research laboratory overlooking the Hudson River in New York City. "When I wake up I enjoy going to work. I feel I'm helping people. I'm saving lives. I'm training the next generation of researchers in the field."

Kleber grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where a musician friend once induced him to cry marijuana. "When I went off to college it never occurred to me to continue using it," he says, noting that his generation was a decade too early to be seduced by the glamour of psychoactive drugs.

He went to Dartmouth with the notion of becoming a doctor. But premed courses bored Kleber, so he took the bare minimum required, preferring to major in psychology and minor in philosoply. He credits his philosophy professor and advisor Fran Gramlich with having influenced him most at Dartmouth.

Kleber never gave up on becoming a doctor, thanks in part to Gramlich, and he earned his medical degree at Thomas Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and went on to Yale for his residency in psychiatry (1961).

With the Vietnam War looming, new doctors were being drafted into the military, so Kleber enlisted instead in the Public Health Service from 1964 to 1966. He was assigned, to his annoyance, to handle admissions at a government hospital in Lexington, Kentucky that was, in reality, a minimum-security prison with 1,000 or so addicted inmates, two-thirds of whom were serving one to 10 years for drug-related crimes.

"It was a fascinating experience," he says. "I didn't know anything about addiction. I read everything I could get my hands on." At 30 years old Kleber had discovered his life's passion.

He was intrigued that 90 percent of the addicts treated at Lexington relapsed a month or two after being discharged—and he wanted to know why. "I found them much more lively and engaging to work with than other patients in the field of psychiatry. They tended to be nonviolent." Kleber pauses. "That changed with the epidemics of crack cocaine and methamphetamine," he adds.

After two years Kleber returned to Yale and secured his first research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to study drug addiction. He worked part time as a psychiatrist at Wesleyan and considered, then turned down, an offer to direct psychiatric health services at Dartmouth. Kleber didn't want to veer from his primary research interest, addiction psychiatry.

While at Yale Kleber set out to determine whether very low doses of the hallucinogen LSD could help break through addicts' resistance to therapy. He had to quit when LSD's notoriety as a street drug dried up the pharmaceutical supply.

Kleber, who argues that drug policy should be driven by science, plunged into his clinical search for effective ways to cure addicts He began with methadone, which blocks the high of heroin. Some critics have derided methadone as hardly better than heroin because methadone is also addictive. But Kleber determined that methadone could be taken safely for at least five years: "We said methadone is a perfectly legitimate approach to treating addiction."

His clinical research has involved testing antagonists—chemical substances that block the action of another substance—on volunteer addicts by also injecting them with heroin or cocaine afterwards, to learn whether they no longer feel high. Far from enjoying free dope, Kleber explains, the addicts do not like to shoot up in a hospital setting under the scrutiny of scientists. The addicts are also offered the opportunity for detoxification and treatment.

The medications for which his team has developed applications include Naltrexone, injected to block the effect of heroin for three days, and Buprenorphine, also injected to block heroin for three to six months. The researchers are cooperating with Australian scientists on an implant of Naltrexone under the skin, effective for a year. Kleber's lab is testing another antagonist to block cocaine, a more intractable narcotic than opiates, for three to six months.

Kleber also suspects that Rimonabant, an antagonist developed in France for nicotine withdrawal and obesity, could be applied to withdrawal from marijuana, but he has yet to secure permission from the French manufacturer to test it.

From May 1989 to November 1991 Kleber set aside his research to serve at the White House as deputy director of national drug policy under drug czar William Bennett. "It was a wonderful experience," Kleber recalls. "We were able to make a number of changes." These included doubling the federal money available to treat addicts and creating more community anti-drug programs.

For 14 years Klebe rworked closely with Marian Fischman, a research psychologist who became his wife. He describes her as "a wonderful partner" and was left bereft by her death from cancer in 2001. Fie remarried in 2004 to Anne Lawver, a photographer friend from Richmond, Virginia.

Kleber s curiosity has not prompted him to try hard drugs himself. "In the dark night of the soul, when you're feeling alone and unhappy, you don't want to know how good drugs feel," he says. 'After the trouble I had giving up smoking I don't want to know how 'good' heroin and cocaine are."

He estimates that 2 to 3 million Americans are addicted to prescription opioids—which have a morphine-like action in the body—including diverted or abused painkillers such as Oxycontin "Hundreds of deaths have been associated with it," he says, "but it's a superb medication if prescribed correctly." While he complains that "doctors are still afraid of giving adequate pain relief," Kleber has low regard for marijuana as medicine. A chemical derivative, Marinol, taken as a pill without marijuana's psychoactive high, he says, is a safer palliative for pain or nausea.

The next frontier for drug research, he says, will involve exploring marijuana, the most popular substance on college campuses after alcohol. "We have trouble stopping marijuana," he says.

Kleber reports that 75 million Americans 12 years and older have tried marijuana at least once. He concedes that the gateway hypothesis that marijuana leads to harder drugs remains unproven. The majority of pot-smokers, he says, "don't go on to all these bad things."

But he cites other findings that 3 to 4 million Americans depend physically or psychologically on marijuana, while 12 to 15 million have.serious trouble with alcohol. If marijuana were made legal, he predicts, stoned potheads could become as numerous as alcoholics.

Marijuana surpasses heroin as the second drug, after cocaine, most cited in trips to hospital emergency rooms, Kleber notes. Smoking pot may pose a particular hazard for adolescents, he says, because "the brain is more vulnerable to adverse affects of marijuana. Heavy use has been shown to impair attention, learning and memory.

Kleber is distressed that barely one-third of American teenagers surveyed say their parents warn them about the risks of illegal drugs. Many parents, he speculates, deceive themselves into thinking, "I used marijuana. I survived. It can't be that bad."

In fact, it's worse, Kleber says.

The psychoactive chemical causing the marijuana high—delta- 9-tetra hydro-cannabinol, or THC for short—is far more potent today than when parents were growing up. And the average age when adolescents start smoking pot has dropped from the late teens a few decades ago to 13 1/2.

"People need to talk to their kids. You can't avoid it," says Kleber, a father of three and grandfather of five. "If you see changes in your child's behavior, you should talk to them."

But how can a parent who smoked pot at Dartmouth (and you know who you are) tell his or her child not to do it without sounding hypocritical?

"You don't need to go into details about what you've done," Kleber says. "If your daughter asks howyou lost your virginity, you don't go into details."

Kleber acknowledges that achieving a drug-free America may impossible. "But it's a statement of hope," he says, "if you can rebe duce the number of people who get harmed."

Kleber is nothing if not hopeful. On his office wall hangs a favorite misquotation from the Talmud:

The day is short,The task is difficult,It is impossible to complete,But we are forbidden not to try.

Kleber confesses that he had fiddled the quotation by deleting one line: "The workers are lazy."

On Herb Kleber's addiction watch, the missing line no longer applies.

Is marijuana nothing more worrisome than the "harmless giggle" casually described by Jonh Lennon?

CHRISTOPHER S. WREN, a former reporter and editorfor The New York Times, unearthed Kleber's Dartmouth roots while interviewing himfora series of Times articles about drug addiction and treatment in 1996.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

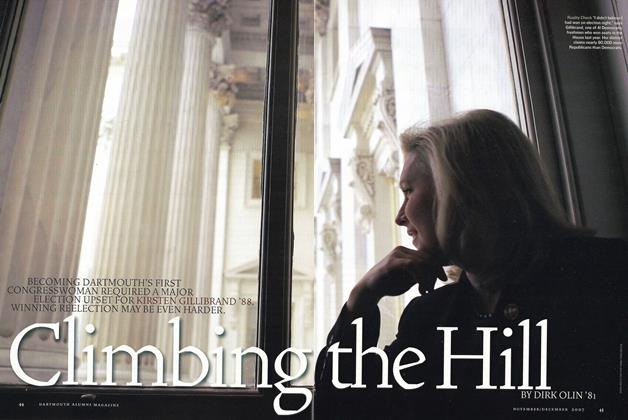

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

November | December 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

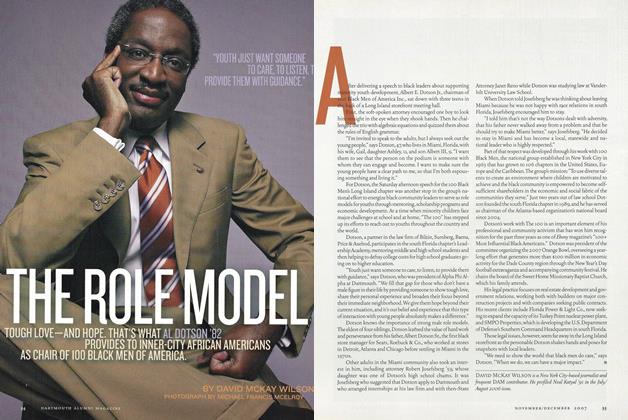

FeatureThe Role Model

November | December 2007 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97 -

ONLINE

ONLINENo Ordinary Joe

November | December 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONWinning Without Weapons

November | December 2007 By Nathaniel Fick ’99

CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57

Features

-

Feature

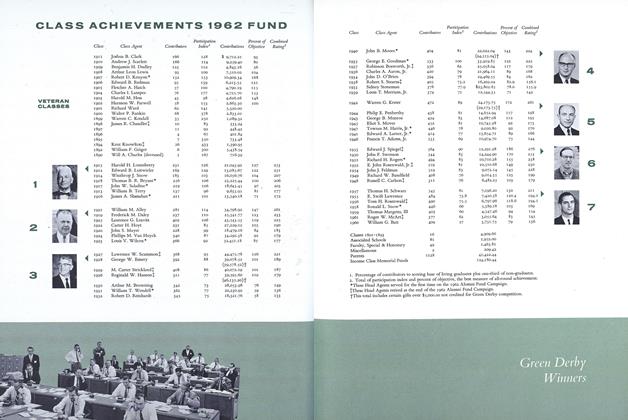

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1962 FUND

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council to Meet

JANUARY 1971 -

Cover Story

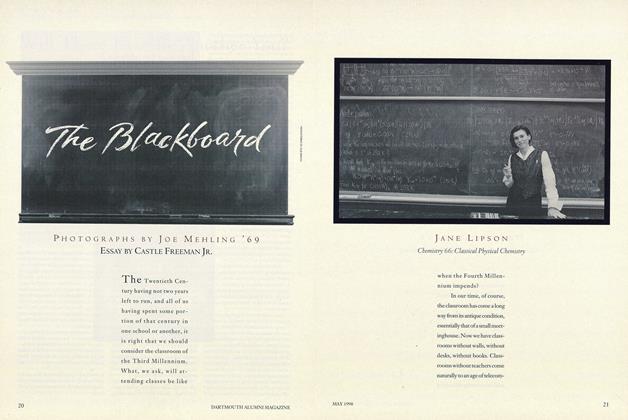

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY -

Feature

FeatureCell Power

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By KRISTIN (COBB) SAINANI ’95 -

Feature

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

NOVEMBER 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT