Students reflect on experiencing their ethnicity in two new collections of essays.

THROUGH A UNIQUE DARTMOUTH CLASS ON IDENTITY AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL writing, minority students at the College have the opportunity to examine the ways that race, ethnicity and culture have affected them in their formative years. Composing memoirs, they clarify the issues involved in growing up, as Ki Mae Ponniah Heussner '01 writes, "in a no man's land between two cultures."

For the past 17 years Andrew Garrod, professor of education and director of teacher education at Dartmouth, has met with students in a one-on-one setting as they focus academic and theoretical knowledge about culture and ethnicity through the magnifying lens of personal experience. Garrod writes that he and his co-editors "have consistently observed that the process of autobiographical writing can have a profound transformative effect on the spiritual, moral and emotional domains of a writers life." (Some of the students chose to write about deeply personal experiences under pseudonyms which are used here without class year identification.)

Garrod is the editor of a quartet of books of minority student memoirs, including a collection of autobiographical essays by African-American students and a collection of memoirs by Native American students at Dartmouth. Two recent volumes of autobiographical writing by Dartmouth students have been published this year: Mi Voz, Mi Vida: Latino College Students Tell Their Life Stories and Balancing Two Worlds: AsianAmerican College Students Tell Their Life Stories (Cornell University Press).

These students carry not only the ordinary concerns of incoming freshmen onto the Dartmouth Green but also an additional history of growing up with dual cultural identities within mainstream American culture. As Korean-American "Patrick S." writes, "Everyone knows that no adolescent wants to stick out in a crowd. The desire to be 'normal' may just be sine qua non of adolescence. Being a member of a minority group made it hard for me, as a teenager, to avoid feeling like I stuck out.'"

Some of the authors, both Asian and Latino, responded to this yearning to belong by denying their ethnicity and heritage. "Jose Garcia," a Honduran-American, writes, "I took pride when my friends told me, 'Jose, you're so white.' As I see it now, I was a sell-out in high school. I was a 'box checker' [someone who takes advantage of minority status], I was a coconut' [brown on the outside, white on the inside]. In college a friend referred to Latino students who didn't recognize their background or culture as 'those who didn't associate.' That was me. I didn't associate."

Other students write that the difficulties inherent in navigating life in two different cultures left them feeling at home nowhere. Sabeen Hassanali '02 writes of "the scalding melting pot in which the traditional and the modern, the old and the young, the Pakistani and the American simmered and collided."

For students whose parents immigrated to America, differences between their parents' attitudes toward child rearing gender relations, sexuality and individualtiy and the attitudes of mainstream American culture create internal tensions. And these tensions are often exacerbated by the fact that these 'star students' carry additional expectations to conform to extremely high standards of behavior and achievement as representatives of their nationality or ethnic group, on top of serving as role models for their siblings and younger extended family members.

A few of the student authors arrived on the Dartmouth campus almost totally identifying with mainstream American culture. Sarah Fox '01 says she felt only a tenuous connection to her Cuban background. "Having grown up in the South, my Hispanic background hadn't been a real factor in my self-identity. Compared to my sisters I had the lightest skin and hair and in school I wasn't singled out as a minority. People assumed I was white, and for all practical purposes that's how I thought of myself. But attending La Alianza meetings and events made me feel closer to home. I had a rich cultural heritage of which I had been unaware."

As described by by Fuyuki Hirashima '00, "balancing on the hyphen" is a process all these students undergo at some point during their formative years, and for many their time at Dartmouth served to illuminate and clarify where they wanted to fall on the assimilation spectrum. While Hirashima decries the "facade of diversity on campus," Garcia writes that, "Despite being 70 percent white, my college introduced me to diversity."

For former student body president Dean Krishna 'O1, a diversity retreat led him to consider how the process of assimilation had indoctrinated him with racist beliefs about his own Indian-American identity.

Another student who went to India on a grant from the Colleges Dickey Center for International Understanding found the trip to be a transformative event in understanding her different identities. She traveled with her mother to Kanya Kumari, a sacred sangam at the southermost tip of India where the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea mix. (A sangam is a meeting of either geographical, physical, spiritual or intellectual bodies.)

"The separate waters are akin to the mishmash of different origins I have felt, within myself, never knowing where I fully belong, if I fully belong," she writes. For all of the authors, the search for the image, the narrative with which to tell their life stories, brings the multifaceted aspects of dual cultural identity into focus.

CATHERINE FAUROT, a regular contributorto DAM, lives in Honeoye Falls, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

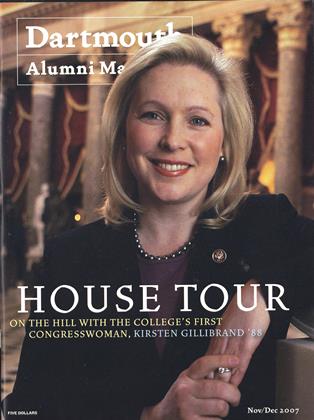

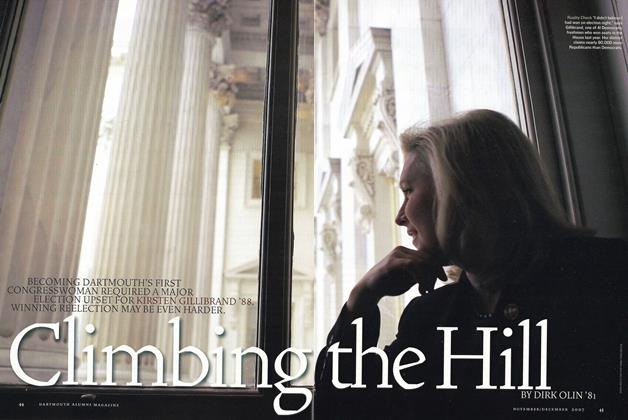

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

November | December 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

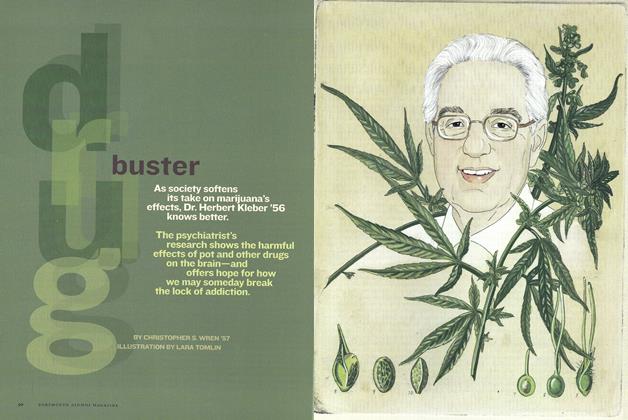

FeatureDrug Buster

November | December 2007 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

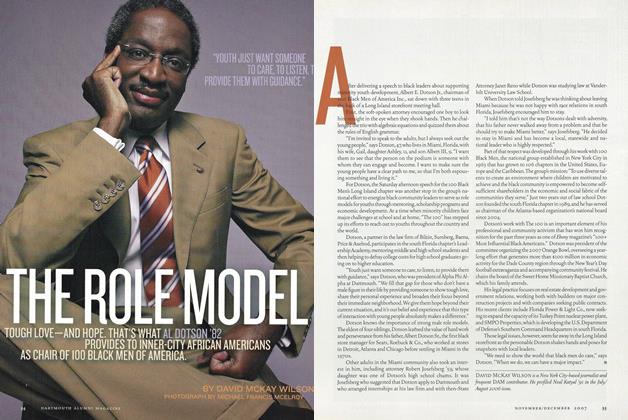

FeatureThe Role Model

November | December 2007 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97 -

ONLINE

ONLINENo Ordinary Joe

November | December 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91