Déjà Vu All Over Again

An expert on the College’s 19th-century alumni dispute puts today’s discord in historical context.

Mar/Apr 2008 Marilyn TobiasAn expert on the College’s 19th-century alumni dispute puts today’s discord in historical context.

Mar/Apr 2008 Marilyn TobiasAn expert on the College's 19th-century alumni dispute puts today's discord in historical context.

TO STUDENTS OF DARTMOUTH HISTORY, TODAY'S FIGHT OVER THE ROLE OF alumni in governing the College may seem eerily familiar. Petition-signing, calls for the presidents head, fiery editorials in national newspapers, threats to withhold alumni donations and prominent alumni attorneys arguing both sides in and out of court: None of these recent events are unprecedented. When it comes to the alumni wars, Dartmouth College has been under siege for more than 150 years.

In the late 18 60s graduates of the College began to demand a greater voice in College affairs. A new breed of alumni—professionals with significant resources from metropolitan areas—had a new conception of community, the College and their role in running the institution. Previously, the majority of students came from poor and middie class families in rural northern New England, and their idea of repaying the institution that had given them their hard-won education was to live good Christian lives.

Harvard alumni won the right to elect alumni to their alma mater's board of overseers in 1865. Ten years later, after schools such as Williams, Yale and Amherst had granted alumni roles on their respective boards, members of Dartmouth's New York association (a precursor of todays alumni clubs) introduced a resolution that alumni be given a voice. They gained the right to fill the boards next three vacancies—electing future president William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861—but many alumni remained dissatisfied, in part because all 10 trustees (excluding two ex officio members) were elected for an unlimited term.

In 1881 members of the New York group, galvanized by the grievances of faculty members, drew up charges against the College president for his theories, policies and administrative practices. President Samuel Colcord Bartlett, class of 1836, who saw the development of moral character as the prime aim of education, favored hiring faculty based on religious rather than scholarly credentials.

While the president's view of himself as the pastoral head of a closely knit, locally oriented college community was in keeping with 19th-century traditions, American society—and Dartmouth—was evolving from its rural roots to a more urban future. Alumni were interested in polishing the Colleges reputation within the big cities and large companies, where the status of one's college was becoming increasingly important in obtaining coveted positions and admittance to certain clubs and associations.

Against this backdrop a trial commenced, with the board of trustees serving as a tribunal. Representing the New York association: prosecutors Asa Tenney, class of 1859, a U.S. district attorney out of New York; Sanford Steele, class of 1870, a prominent lawyer, businessman and treasurer of the New York association; and Judge William Fullerton, class of 1824, a leader of the New York Bar. Bartlett's defense counsel included the Hon. Harry Bingham, class of 1843, and Judge William Ladd, class of 1855, prominent members of the New Hampshire Bar. For witnesses, prosecutors called on the 16 of 23 faculty members who had signed petitions against the president, as well as students, who had little interest in Bartlett's sermons on discipline. It's likely students saw New York's urban alumni as valuable connections who might help launch careers. It also appears from student testimony that alumni may have encouraged some students to consider post-graduation governance roles. As one student noted during the trial, "Well, being nearly graduates...[we] might have a chance to get on the board of trustees, and we should probably like to see into the action and see how these things are managed."

The trial gave alumni an opportunity to publicize their demands in the press, generate increased support for alumni representation on the board and, ultimately, win that right (through a trustee resolution passed in 1891). More than 20 newspapers covered the trial and its aftermath. Some alumni used these newspapers to express dissatisfaction with the president. "The alumni of the College have come to its rescue," wrote New York Times editor Charles Ransom Miller, class of 1872, the secretary of the New York alumni association. "The graduates of a college are its natural governing body," he continued, using words that echo those found more recently in The Wall Street Journal, where Paul Gigot '77 oversees the opinion pages. "To exclude [alumni] from all representation in its councils alienates their affections, and no college can afford to lose the sympathy of its graduates."

The trustees did not dismiss,Bartlett in the wake of the unprecedented trial, although the process did expose the board's ideological fault lines: Nine months later four trustees on the 10-member board cast votes of no confidence in the Bartlett administration. The majority prevailed, allowing Bartlett to stay on for another 11 years. While they were sensitive to pressure from alumni because of their potential for support, trustees did'not want to completely reject the traditional values, and so left Bartlett in place until he retired in 1892. The board praised the alumni, urged all parties to work together and noted that the College was unexpectedly better off financially than it had been in many years—in part due to Bartlett s efforts.

Nonetheless, alumni continued to claim that Dartmouth was in a financial and educational crisis and that it needed different leadership.

Their agitation led to a June 23,1891, board resolution that gave graduates at least five years out the right to "nominate a suitable person for election to each of the five trusteeships next becoming vacant" (except for the president and the governor) and "may so nominate his successors." The alumni had gained half the seats on the board, but there was no language ensuring parity in perpetuity. The alumni association, however, decided it would have alumnielected trustees serve only five-year terms; charter trustees would still serve for life (this was changed in 1970 to a five-year term; all trustee seats went to four-year terms in 2003).

President William Jewett Tucker, who took over from Bartlett in 1893, recognized the importance of alumni to a "new Dartmouth" he spoke of. He noted the role of alumni—and their increased responsibility—in his inaugural address: "The advantage of this responsible representation will depend upon the character, the educational and business qualifications and the personal time available for the College, on the part of the alumni trustees and equally upon the spirit of unity, of cooperation and of active loyalty, which it assumes in the alumni at large. I draw no unwarranted inferences from this action in respect either to men or money."

Tucker engaged in a step-by-step process to educate alumni about developments at Dartmouth and its needs. He visited alumni on their own territory, especially the New York and Boston groups, and he effectively utilized the language they had used during the time of the Bartlett trial—and later—to stress that the new alumni representation included the additional responsibilities of providing financial resources to the College, encouraging students to attend and helping new graduates.

Which leads us to the current governance battle, again playing out across national newspaper pages, at divisive alumni association and trustee meetings and in a New Hampshire courthouse. Regardless of the outcome of the current suit led by six members of the Association of Alumni, the debate over the proper role of alumni in determining the future of the institution will likely rage for many decades to come.

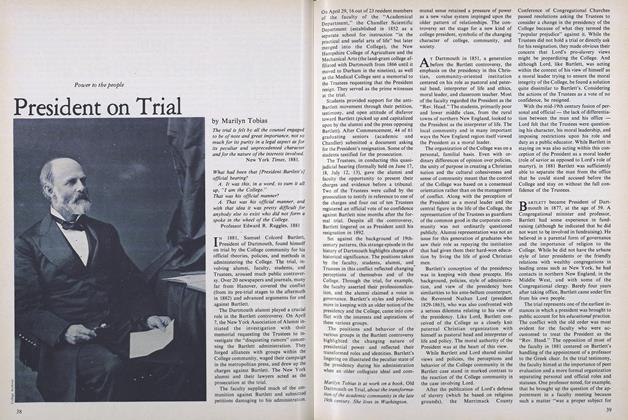

Dogfight The battlebetween Bartlett (middle,with white beard) andfaculty, later joined byalumni, was depicted inthe 1884 .Aegis with thisstudent-drawn lithograph.

As opposition mounted, Bartlett was put on trial before a tribunal of trustees.

MARILYN TOBIAS is an historical and educational consultant in New York City. She is theauthor of Old Dartmouth On Trial: The Transformation of the Academic Community in Nineteenth-Century America (NewYork University Press, 1982, reprinted 2002).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Numbers Game

March | April 2008 By LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02 -

Feature

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

March | April 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

Feature

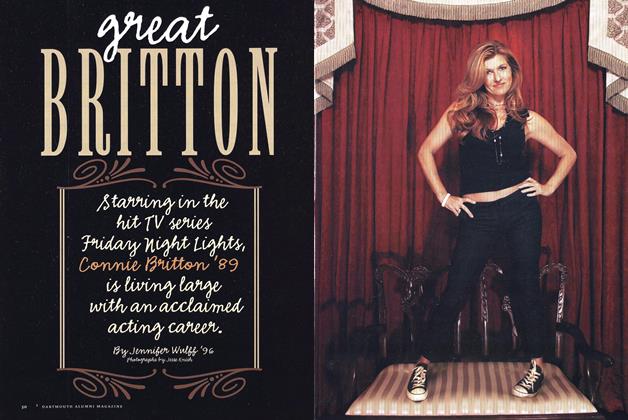

FeatureGreat Britton

March | April 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Interview

Interview“The Timing is Right”

March | April 2008 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

March | April 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLiving Room Learning

March | April 2008 By Jane Varner Malhotra '90

Marilyn Tobias

HISTORY

-

HISTORY

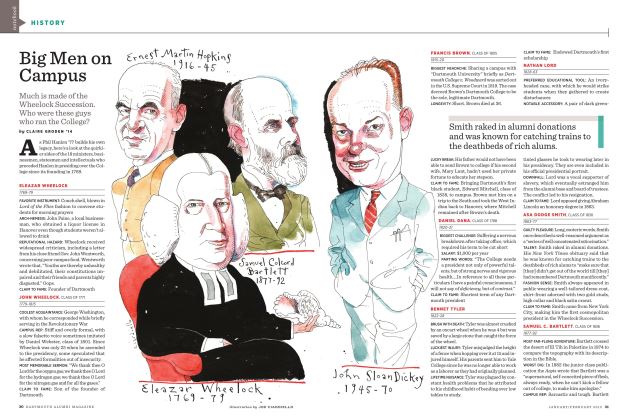

HISTORYBig Men on Campus

JAnuAry | FebruAry By CLAIRE GRODON ’14 -

HISTORY

HISTORYA Nuanced Culture Clash

May/June 2012 By Jay Pridmore -

History

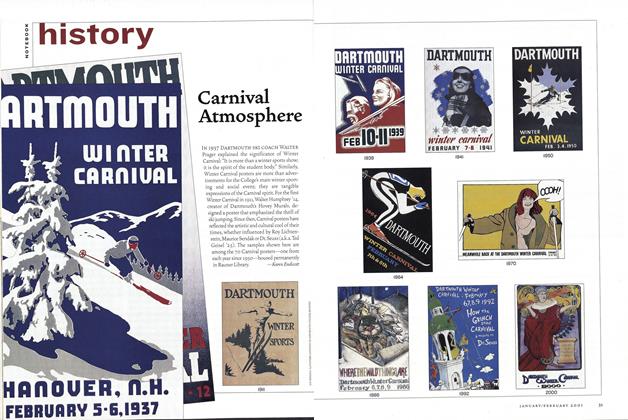

HistoryCarnival Atmosphere

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott -

HISTORY

HISTORYThe Chosŏn One

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By KARL SCHUTZ ’14 and JUN BUM SUN ’14 -

HISTORY

HISTORYTalk of a Great Revival

Sept/Oct 2010 By Peter Slavin ’63 -

HISTORY

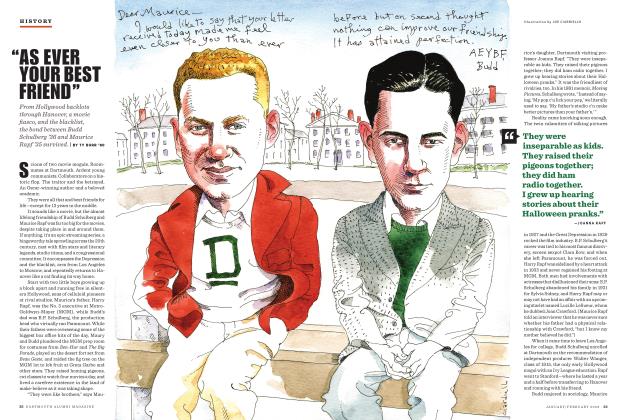

HISTORY“As Ever Your Best Friend”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By TY BURR ’80