Power to the people

The trial is felt by all the counsel engagedto be of note and great importance, not somuch for its purity in a legal aspect as forits peculiar and unprecedented characterand for the nature of the interests involved.

New York Times, 1881.

What had been that [President Bartlett's]official bearing?

A. It was this, in a word, to sum it allup, "I am the College."

That was his official manner?

A. That was his official manner, andwith that idea it was pretty difficult foranybody else to exist who did not form aspoke in the wheel of the College.

Professor Edward R. Ruggles, 1881

In 1881, Samuel Colcord Bartlett, President of Dartmouth, found himself on trial by the College community for his official theories, policies, and methods in administering the College. The trial, involving alumni, faculty, students, and Trustees, aroused much public controversy. Over 20 newspapers and journals, many far from Hanover, covered the conflict (from its pre-trial stages to the aftermath in 1882) and advanced arguments for and against Bartlett.

The Dartmouth alumni played a crucial role in the Bartlett controversy. On April 7, the New York Association of Alumni initiated the investigation with their memorial requesting the Trustees to investigate the "disquieting rumors" concerning the Bartlett administration. They forged alliances with groups within the College community, waged their campaign in the metropolitan press, and drew up the charges against Bartlett. The New York alumni and their lawyers acted as the prosecution at the trial.

The faculty supplied much of the ammunition against Bartlett and submitted petitions damaging to his administration. On April 29, 16 out of 23 resident members of the faculty of the "Academical Department," the Chandler Scientific Department (established in 1852 as a separate school for instruction "in the practical and useful arts of life" but later merged into the College), the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanical Arts (the land-grant college affiliated with Dartmouth from 1866 until it moved to Durham in the nineties), as well as the Medical College sent a memorial to the Trustees requesting that the President resign. They served as the prime witnesses at the trial.

Students provided support for the anti-Bartlett movement through their petition, testimony, and open attitude of disfavor toward Bartlett (picked up and capitalized upon by the alumni and the press opposing Bartlett). After Commencement, 44 of 61 graduating seniors (academic and Chandler) submitted a document asking for the President's resignation. Some of the students testified for the prosecution.

The Trustees, in conducting this quasi-judicial hearing (formally held on June 17, 18, July 12, 13), gave the alumni and faculty the opportunity to present their charges and evidence before a tribunal. Two of the Trustees were called by the prosecution to testify in reference to one of the charges and four out of ten Trustees registered an official vote of no confidence against Bartlett nine months after the formal trial. Despite all the controversy, Bartlett lingered on as President until his resignation in 1892.

Set against the background of 19th-century patterns, this strange episode in the history of Dartmouth highlights changes of historical significance. The positions taken by the faculty, students, alumni, and Trustees in this conflict reflected changing perceptions of themselves and of the College. Through the trial, for example, the faculty asserted their professionalization, and the alumni claimed a voice in governance. Bartlett's styles and policies, more in keeping with an older notion of the presidency and the College, came into conflict with the interests and aspirations of these various groups.

The positions and behavior of the various groups in the Bartlett controversy highlighted the changing nature of presidential power and reflected their transformed roles and identities. Bartlett's lingering on illustrated the peculiar state of the presidency during his administration when an older collegiate ideal and com-Marilyn munal sense retained a pressure of power as a new value system impinged upon the older pattern of relationships. The controversy set the stage for a new kind of college president, symbolic of the changing character of college, community, and society.

AT Dartmouth in 1851, a generation before the Bartlett controversy, the emphasis on the presidency in this Christian, community-oriented institution centered on his role as pastoral and paternal head, interpreter of life and ethics, moral leader, and classroom teacher. Most of the faculty regarded the President as the "Rev. Head." The students, primarily poor and lower middle class, from the rural towns of northern New England, looked to the President as the interpreter of life. The local community and in many important ways the New England region itself viewed the President as a moral leader.

The organization of the College was on a personal, familial basis. Even with ordinary differences of opinion over policies, the unity of purpose in creating a Christian nation and the cultural cohesiveness and sense of community meant that the control of the College was based on a consensual orientation rather than on the management of conflict. Along with the perception of the President as a moral leader and the central figure in the life of the College, the representation of the Trustees as guardians of the common good in the corporate com- munity was not ordinarily questioned publicly. Alumni representation was not an issue for this generation of graduates who saw their role as repaying the institution that had given them their hard-won education by living the life of good Christian men.

Bartlett's conception of the presidency was in keeping with these precepts. His background, policies, style of administration, and view of the presidency bore similarities to his ante-bellum counterpart, the Reverend Nathan Lord (president 1829-1863), who was also confronted with a serious dilemma relating to his view of the presidency. Like Lord, Bartlett conceived of the College as a closely knit paternal Christian organization with himself as pastoral head and interpreter of life and policy. The moral authority of the President was at the heart of this view.

While Bartlett and Lord shared similar views and policies, the perceptions and behavior of the College community in the Bartlett case stand in marked contrast to the reaction of the College community in the case involving Lord.

After the publication of Lord's defense of slavery (which he based on religious grounds), the Merrimack County Conference of Congregational Churches passed resolutions asking the Trustees to consider a change in the presidency of the College because of what they termed the "popular prejudice" against it. While the Trustees did not hold a trial or directly ask for his resignation, they made obvious their concern that Lord's pro-slavery views might be jeopardizing the College. And although Lord, like Bartlett, was acting within the context of his view of himself as a moral leader trying to ensure the moral integrity of the College, he found a solution quite dissimilar to Bartlett's. Considering the actions of the Trustees as a vote of no confidence, he resigned.

With the mid-19th century fusion of personal and official - the lack of differentiation between the man and his office Lord felt that the Trustees were questioning his character, his moral leadership, and imposing restrictions upon his role and duty as a public educator. While Bartlett in staying on was also acting within this conception of the President as a moral leader (role of savior as opposed to Lord's role of martyr), in 1881 Bartlett was sufficiently able to separate the man from the office that he could stand accused before the College and stay on without the full confidence of the Trustees.

BARTLETT became President of Dartmouth in 1877, at the age of 59. A Congregational minister and professor, Bartlett had some experience in fundraising (although he indicated that he did not want to be involved in fundraising). He believed in a parental form of governance and the importance of religion to the College. While he did not have the urbane style of later presidents or the friendly relations with wealthy congregations in leading areas such as New York, he had contacts in northern New England, in the Middle West, and with some of the Congregational clergy. Barely four years after taking office, Bartlett came under fire from his own people.

The trial represents one of the earliest instances in which a president was brought to public account for his educational practice. The conflict with the old order was most evident for the faculty who were accustomed to treat the President as the "Rev. Head." The opposition of most of the faculty in 1881 centered on Bartlett's handling of the appointment of a professor to the Greek chair. In the trial" testimony, the faculty hinted at the importance of peer evaluation and a more formal organization separating personal and official roles and statuses. One professor noted, for example, that he brought up the question of the appointment in a faculty meeting because such a matter "was a proper subject for discussion in faculty meeting," it should not be "acted upon by the [Trustees] without its formal discussion . . . among the faculty," and, therefore, he "brought it up in the only meeting in which we have official intercourse together." (In other words, consensus en famille was giving way to the notion of faculty autonomy, and it was increasing the distance between the President and the faculty.) Bartlett, on the other hand, explained that while he did not object to informal faculty consultation under certain circumstances, this was not a faculty prerogative.

In contrast to an earlier emphasis on spiritual suitability, the faculty now emphasized the importance of scholarly reputation and status. They stressed that the Greek chair "should be filled by a man in these times who enjoyed in his own department, no matter how good a minister he was, or how good a man, the respect and confidence of Greek scholarship in this country." Bartlett, for his part, told the faculty that in discussing the reputation of the proposed appointee according to the standards laid down at the meeting (national reputation in his discipline and worthy publications), they all would be found wanting.

While the faculty felt that they "had been treated in an unwarrantable manner," Bartlett, unable to grasp the changing order of authority, stated that he was just "putting the whole thing in the right aspect." He explained that the candidate had impressive credentials (a fine man, minister, and teacher), he had his recommendation, he thought he had the as-sent of the professors to whom he showed the recommendations. Therefore, he didn't see how the discussion could influence the election.

The members of the Chandler Department and the agricultural school registered complaints similar to that of the academic faculty; moreover, they viewed Bartlett's policies and attitude as detrimental to the status of the schools and the fields of study they represented. In a series of steps, Bartlett had questioned the status of the Chandler Department before the Trustees. While they did not completely agree with Bartlett's position, the Trustees passed some measures, such as a lowering of some entrance requirements, which the faculty saw as debasing their school and their positions. Bartlett thought the academic department had a better moral influence on the students and objected to the portrayal of the scientific department as a "liberal education on a scientific basis," feeling this might be attracting students away from the classical course. He also made obvious his low opinion of the education offered by the agricultural school.

Ironically, the faculty's efforts to transfer power to themselves was not clearly a gain for the faculty, and the full impact of their initiatives was carried forward not by the faculty but by the alumni. Reflective of the changing sense of community and character of the presidency, the trial became a means for the alumni to voice their opposition to a President who they perceived as a failure "as an administrative and executive officer" and to assert their demands for representation as alumni on the Board of Trustees. Increasingly moving to metropolitan areas and engaging in business-related positions, the alumni were competing with graduates of other colleges in these areas. The college one attended or the club to which one belonged began to be important factors in selection for a position and for business and social success. No doubt this was one reason why the alumni, especially the alumni from New York, a leading urban area and the center of upperclass life by 1880, were so concerned with the status of the school. The alumni were primarily concerned with the College's metropolitan reputation - a reputation defined according to national standards emanating from these leading centers - not its services to the hill country of New Hampshire.

Wearying of a domain dominated by personality and the work of one man, the alumni sought (and ultimately succeeded) to transform the very scope of collegiate control. The members of the New York Association perceived themselves as leaders in the alumni movement for a greater voice in the governance of the institution. (It was through a resolution presented by the New York alumni in 1876 that the alumni gained their first limited measure of representation.) In 1881, the secretary of the New York Association referred to the board as a closed corporation. He remarked that the initiation of an investigation of the state of affairs of the College would lead to the discovery of the source of the problem, that "the credit of the result will belong chiefly to the New York alumni," and that "this is an important step toward the admission of graduates of the college to a share in its management." The New York alumni seemed to be saying that had they been on the Board of Trustees, Dartmouth would not be in danger of "ruin" or "impending disaster" through Bartlett's "deplorable management." The "impending disaster" referred to the College's status and potential for growth, numbers and type of students, rank, sources of support, and its ability to attract and keep faculty of distinction in essence, to its metropolitan reputation as' a leading Eastern college. Through achieving power on the board, these aspiring upper-middle-class graduates sought to represent their interests and "modernize" and "improve" the institution.

Student protests and disciplinary incidents were not new to 19th-century colleges. In contrast to the mid-century students, however, the students in 1881 did not regard the President as an authority figure, a model they could emulate but never quite reach. Bartlett's pastoral approach, his style emphasizing himself as "supreme head" and interpreter of life, and his rigid policy of discipline, which was linked to his conception of higher learning (firm discipline aided in character-building), clashed with students who were beginning to define their aims and aspirations in relation to different models. The students of the Chandler Department had additional grievances against the President who had openly questioned whether their course was equal to the traditional liberal arts program. Dartmouth students now saw themselves as part of a more broadly conceived collegiate culture. And they consciously linked their ambitions to men like the New York alumni.

The Trustees were most conscious of the confusions between old and new traditions. Initially, they appeared to be in agreement with the alumni (a new power with much potential for financial support). The decision to hold this public trial, the open challenge to the authority of the President, the desire to clear it all up once and for all and decide who was blameworthy, the preoccupation with finances all signified that position. But then the Trustees also seemed to be acting as the moral guarantors of the College. In their own transition during the trial, there was an implied sympathy' for Bartlett's position as they balanced the moral authority of the President and the College's books. In their quandary, in the end, with all the charges lodged, they did not ask for his resignation, but sought an older form of harmony that would accommodate- the new realities.

The Trustees began to emphasize important aspects of what would be the President's modern role, such as his ability to reconcile the various groups in the College community. In this context, they noted with concern the inharmonious relations of the faculty with Bartlett "in their official intercourse." Their decision in their report to list the institution's promising financial condition at the top of the category, "Satisfactory Condition of the College," emphasized the administrative capacity of the President. Even after the trial however, when the controversy continued, a majority of the board stopped short of removing Bartlett, and he was allowed to stay on until he resigned 11 years later. The Trustees stopped short of completely rejecting the old values, so they left Bartlett in place. But when it came to choosing his successor, they chose a minister who excelled in the mediator's role and who would attend to the wider world and the harsh realities of money.

THE Bartlett controversy, then, forecast the shift in presidential power and highlighted the changing nature of the academic community. While neither the ideal of unity nor the older sense of responsibility to the local community were completely abandoned, Dartmouth in 1881 was no longer an organically knit order expressive of its local community. It served a different clientele - younger, from a higher socio-economic stratum and a wider geographic background. The faculty had changed; through the trial they publicized their more cosmopolitan and professional ambitions. Status began to be defined according to standards emanating from metropolitan areas instead of the traditional local context. Groups sought to protect their interests and influence the direction of the institution by achieving power within the College. A more formal organization, differentiating personal and official roles, began to replace the older model of family or congregation. All of these changes forced the emergence of a new type of college president.

The kind of president now needed to administer and shape the "new Dartmouth" was realized in the administration of Bartlett's successor, the Reverend William Jewett Tucker. In an organization choosing to remain a college, with its emphasis on its homogeneity, its religious spirit, and the primacy of teaching, the notion of the President as a moral leader was not abandoned, but transformed and redefined. Added to this altered notion was an increased emphasis on the President as an administrative officer who could ensure the College's metropolitan reputation and bring Dartmouth into the position of prominence in late 19th-century America it had once held in the northern New England.

One of Tucker's first duties began at home with the reconciliation of the increasingly powerful College factions. Highlighting their rise in power, in 1891 the alumni obtained the recognition of their right to representation as alumni on the Board of Trustees. Excluding the President and the governor of New Hampshire, the alumni gained half of the seats on the board. While the faculty did not realize all their demands for autonomy under Bartlett or Tucker, they did gain some recognition with the exposure of the issue. In new appointments, especially during the Tucker administration, they realized to a considerable extent their demands for a more professionalized faculty. The students, for their part, were now able to tout to each other the many advantages of a broader fellowship of "college life, not college work." Within this altered framework. Tucker tried to reconcile the various factions by emphasizing the oneness of their position as members of a select fellowship. Outwardly, the rhetoric of community and moral purpose continued under President Tucker and provided continuities into the 20th century. But by that time these terms had taken on a meaning completely foreign to Dartmouth's 19th-century leaders like Samuel Bartlett.

Charles Ransom Miller, theyouthful editor of the NewYork Times, was one ofBartlett's powerful adversaries. A member of theClass of 1872, Miller wasdeemed "unworthy" as a student. His life's goal, he saidthen, was to win at croquet.

According to Bartlett, permitting alumni representation on the Board ofTrustees was "the gravest mistake in the history of the College.' Afterresigning in 1892, he remained a familiar figure on Main Street and taughta required course on the Bible and science to seniors. He died in 1899.

Tobias is at work on a book, Old Dartmouth on Trial, about the transformation of the academic community in the late19th century. She lives in Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDr. Hot's Thermal Therapy

January | February 1979 By Bill Galvin -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Sod: Summits Above and Graves Below

January | February 1979 By Ann Lloyd McLane -

Feature

FeatureWomensports

January | February 1979 -

Article

ArticleWriter Possessed

January | February 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleIt Flew

January | February 1979 By TIM TAYLOR '79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

January | February 1979 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTurkeys for Dartmouth

April 1955 -

Feature

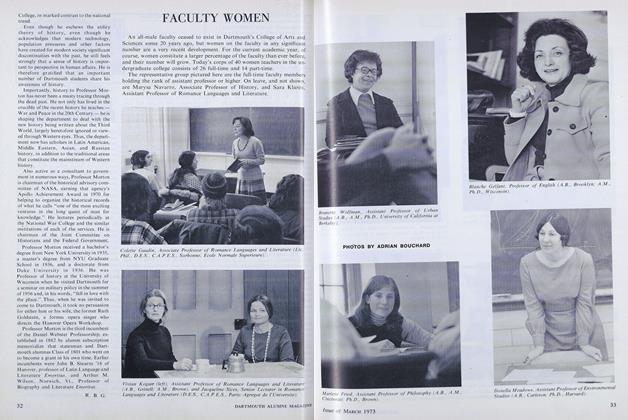

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

MARCH 1973 -

Feature

FeatureHanover's Bests

DECEMBER 1984 -

FEATURES

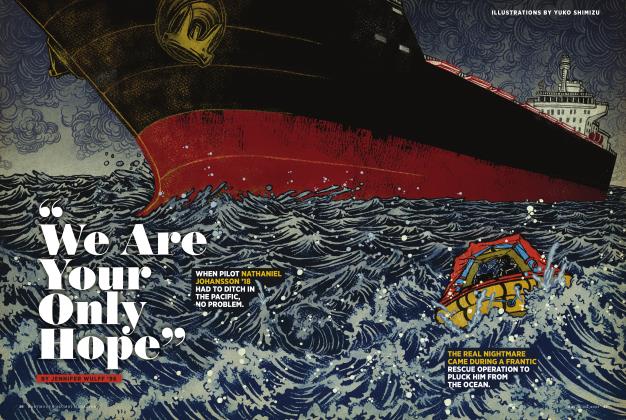

FEATURES“We Are Your Only Hope”

MAY | JUNE 2023 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

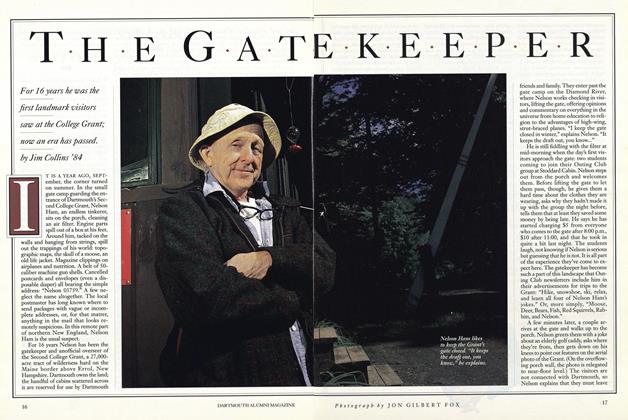

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

FEATURES

FEATURESMoving Pictures

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By RICHARD BABCOCK '69