Learning Experience

Four years at Dartmouth changes many lives—and not just those of students. A former administrator looks back fondly.

July/August 2008 Susan MarineFour years at Dartmouth changes many lives—and not just those of students. A former administrator looks back fondly.

July/August 2008 Susan MarineFour years at Dartmouth changes many lives—and not just those of students. A former administrator looks back fondly.

ON AN ALMOST SURREALLY PERFECT day in late September I was married to my long-time sweetheart in a ceremony overlooking Provincetown, Massachusetts, harbor, surrounded by friends from Dartmouth. None of this is especially remarkable, as events like it happen every week of every year. But what makes it somewhat unusual is the nature of my Dartmouth experience. I never attended a single class in Dartmouth Hall. I never slept in a bed in New Hamp, Topliff, Mid Fayerweather, the Choates or any other dorm room. I never spent a Friday night, fading into Saturday morning, in the basement of a fraternity on Webster Avenue. I never sang the alma mater in the Bema on class day and I never once wore a green article of clothing to any Dartmouth sporting event. I never hiked up Moosilauke and I never danced the "Salty Dog Rag."

No, I wasn't a loner or a misfit. I was an administrator on campus from 1996 to 2000. In that time I grew in unexpected ways, mostly by simply taking part in the daily life at Dartmouth. One doesn't have to be a student at the place to experience every moment of splendor and growth it has to offer. One only has to be open to drinking it all in.

When I left the hippie hinterlands of central Colorado for the rarified air of Dartmouth I received several telling gifts from friends at my erstwhile employer. A sumptuous, cascading potted ivy plant that to this day sits front and center on my desk. A pair of genuine beaver-skin earmuffs, appropriate for 40 degrees below zero. And the piece de resistance: a monocle, on a chain, harkening back to the days when such accessories were sported unremarkably by the all-male student body of the 19th century.

The subtle metaphor I took from those talismans said plainly: See your new home clearly for what it is, and be sure to bundle up. I stepped into the Upper Valley feeling both a great sense of adventure and a vague sense of dread. I wondered if I would fit. Would I find the kind of home I had in Colorado, where it was enough to be a hardworking girl from Indiana with a penchant for familiarity? Would I survive the winter—and would I actually find a decent cup of coffee in the middle of the night in a town with two stoplights?

I harbored no illusions about what I was walking into in terms of my job. As the coordinator of Dartmouth's sexual abuse awareness program, I would spend my days listening to stories of the profound suffering and healing of students who had survived sexual and domestic violence. Long days and nights followed, working in close collaboration with colleagues in the administration and faculty who were convinced that Dartmouth could aspire to be a place where such a position would be blessedly obsolete. Then and now I feel deeply privileged to have been able to bear witness to a newly inspired commitment to non-violence in the students with whom I worked. The term "aha moment" is often employed to describe the click of understanding that college students experience when they begin to grasp a complex social issue for the first time in new and reflectively meaningful ways. More than once watching a Dartmouth student arrive at that moment of realization resulted in so much more than job satisfaction.

I was fortunate to experience my four years at Dartmouth during times of immense transformation. I watched in astonishment as students I knew and respected took immensely difficult personal stands for what they believed would make Dartmouth a better, more just, more inclusive place. I witnessed the sparks of impassioned student activism brought on by the advent of California Proposition 209, which eliminated the states affirmative action programs. I cheered the Dartmouth football team on as it played an undefeated season and the women's hockey team as it sent its star to the 1998 Olympics. I watched Meryl Streep reminisce about her days as an exchange student at Dartmouth as she received a lifetime achievement award for acting, and attended an intimate dinner party with pioneering gay rights activist Urvashi Vaid. I contemplated the. stars while lying on the Green, and I sighed with delight at my first taste of cider from nearby Poverty Lane orchards.

I spent many sleepless nights wondering how I might be more useful in service to the extraordinary community I was part of, how I might better understand what it might take to realize all of its potential and how, creatively, to bridge the gap between faculty and administrative life. Such late-night ponderings were not those of a martyr. I'll never fully feel that I can repay the debt of precious human investment that was made in me during my four years in Hanover. The colleagues-cum-friends I encountered offered me the most sincere blend of personal integrity and kindness I've ever known. I received fiercely protective mentorship from strong, principled women. I bathed in the warm generosity of the übiquitous nuclear families that embraced me (as a single person) as if I was one of their own. I still flinch whenever anyone unfamiliar with it mislabels Dartmouth as a quirky place fit only for wilderness-loving hoi polloi. Being neither, I can attest that it's still possible to make a living and make a life in a place with—gasp—no mall and no trash pickup.

Which isn't to say it was a cakewalk from the sunny day in June when I arrived to the early autumn day four years later when I left. Despite the deep joy I derived from my work, I struggled with what was missing: a life of my own, independent of all things Dartmouth. I had found love in Boston and felt increasingly pulled to a life with the things that stirred my soul more readily: instant and daily access to live music, the lapping of ocean waves on my feet (for which the Connecticut is a lovely but distant substitute)—and that 2 a.m. coffee thing. None of these are a fixed part of the landscape of the Upper Valley, and it is none the worse for it. But when these became the things necessary to my particular sense of what life is about, their absence was not only inconvenient, it was palpable. I was eventually driven to distraction by longing and began my leaving for the big city, my wife-to-be and the possibility of an equally gratifying professional home at that quaint little college on the Charles.

And so it was with some surprise and with great delight that I found myself five years later surrounded by my Dartmouth family on the happiest day of my life. They were all there—the former students whose brilliance inspired me to realize that age and intellect are not mutually exclusive categories, and the fellow administrators in whose image I continue to mold my own evolving professionalism—the leaders of student life, gender equity, racial justice and athletics who give their hearts, minds and considerable talents to the place. Surrounding me were the faces of gifted alumni, faculty and administrators—and some who were all three. Beloved and quirky and human, and among the dearest friends I have or will ever have.

So I'll never dance the "Salty Dog Rag" and I'll never know what it was like to meander down the Connecticut in an inner tube full of beer. I'll never canoe to Maine with seven other seniors and I'll never offer my bed to a through-hiker who smells pungently of 400 miles. But the Dartmouth experience was mine in spite of the fact, or perhaps because, I was never a student. I would never trade a moment of it, and I will always be indebted to the people and place that gave me four of the best years of my life.

One doesn't have to be a student to experience the splendor and growth Dartmouth offers.

SUSAN MARINE, an adopted member of the class of 2000, directs Harvard University's women's center. She lives in Waltham, Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

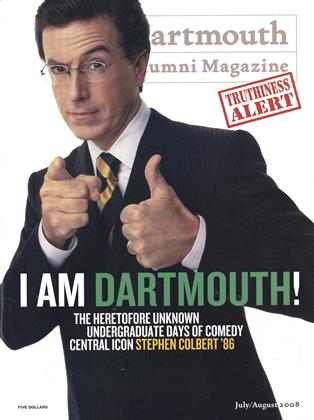

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July | August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Feature

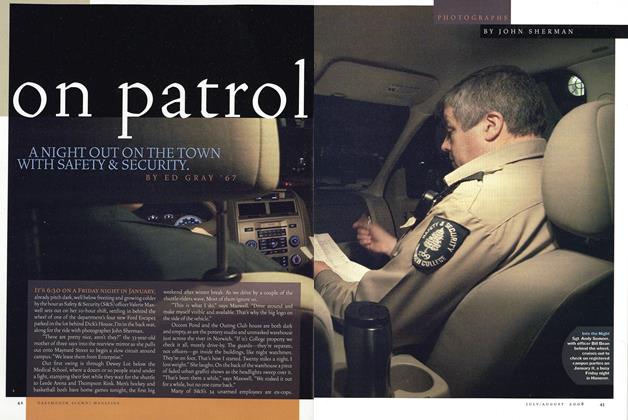

FeatureOn Patrol

July | August 2008 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

FeatureThe Artful Lodger

July | August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2008 By John Kemp Lee '78 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2008 By BONNIE BARBER

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

Mar/Apr 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May/June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Devil and Dan Club

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jim Collings ’84 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

Sept/Oct 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryRiver Dance

Sept/Oct 2002 By Jonathan Agronsky ’68 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66