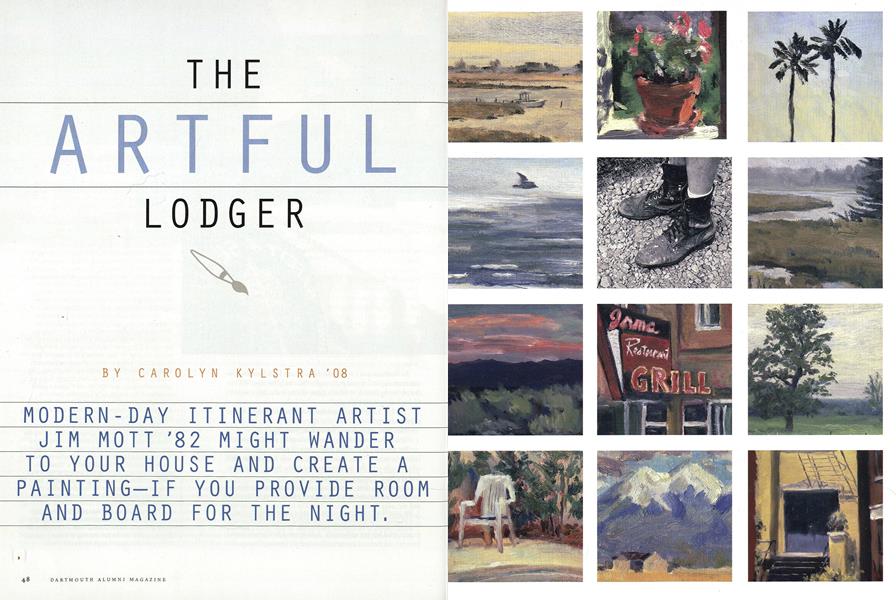

The Artful Lodger

Modern-day itinerant artist Jim Mott ’82 might wander to your house and create a painting—if you provide room and board for the night.

July/August 2008 Carolyn Kylstra ’08Modern-day itinerant artist Jim Mott ’82 might wander to your house and create a painting—if you provide room and board for the night.

July/August 2008 Carolyn Kylstra ’08MODERN-DAY ITINERANT ARTIST JIM MOTT '82 MIGHT WANDER TO YOUR HOUSE AND CREATE A PAINTING-IF YOU PROVIDE ROOM AND BOARD FOR THE NIGHT.

On October 1, 2007, Jim Mott '82 got a speeding ticket. Instead of paying money for his transgression, Mott settled his fine with art.

It began as a normal enough traffic stop. Mott was passing through Missoula, Montana, on his way to Yellowstone, five hours away. He was in a rush to beat a rainstorm brewing in his rearview mirror, and the officer pulled him over for going 40 in a 30. The officer told him to call the judge in several weeks to arrange the penalty.

The courthouse clerk chose a print from Mott's collection, which she was able to view online at his Web site, www.jimmott. com. Mott's prints cost $125 matted and framed, slightly more than the actual cost of the ticket. The clerk chose a kitchen scene Mott had painted in Connecticut several years before. "She said the colors would go well with the courthouse," Mott says. On his Web site Mott notes that the judges willingness to get into the spirit of his endeavor, called the Itinerant Artist Project (IAP), was a highlight of the two-month trip he started last September. Mott has gone on seven such tours in as many years, traveling from coast to coast twice. In the 20,000-plus miles he's driven for the lAP he's painted about 350 small landscapes.

He has received only one speeding ticket.

Mott, who double-majored in religion and visual studies at Dartmouth (brother John '81 and sister Emily '86 also attended the College), says he first conceived of the IAP in 1997, when a folksinger friend joked that if Mott intended to live as an artist he'd have to get used to sleeping in other peoples houses. The folksinger's comment was well timed—Mott had recently read The Gift by Lewis Hyde, a nonfiction explanation of gift economies. The book articulated a belief Mott had long held—that art is a gift, and when it becomes a commodity the relationship between the artist, the art and the public becomes distorted.

"I was having trouble accepting the way the gallery system worked—the commercialization of art just bothered me," Mott says. "The book gave me the idea of finding some way to practice art in which it could be just a gift."

He says he developed the concept of the LAP for a complex set of reasons, from wanting a personal challenge.to wanting to see if art could be more connected to peoples' everyday lives. 'Another reason was that the Internet was starting to get popular, and I didn't like the idea of people experiencing art on the Internet," he says. "It's kind of ironic, because now I have a Web site and that's how most people see my art. In any case, it really bothered me that people were getting isolated by technology and not meeting face to face enough, and I wanted to challenge that in myself and others."

The logistics were daunting. "The project involved a lot of things that I'm really uncomfortable doing," he says. "Like traveling." He also wasn't sure if he would be able to paint in a new place or new setting without several weeks of acclimation. "I don't like change in my environment or lack of control, and I don't sleep well in new places," he says.

It took him three years but Mott finally worked up the nerve to give it a try. He took out an ad in The Nation, seeking hosts. "ITINERANT ARTIST PROJECT," the ad read. "Exchanging landscape paintings for hospitality across the U.S." He also sent e-mails to friends, asking them to forward the messages. His ad and his e-mails proved fruitful. From March 31 to June 14,2000, Mott made 31 different stops across the country, painting landscapes wherever he went. He stayed with each host for one to four days and painted about two landscapes a day. Each time he left for a new location he asked his host which painting he liked the best. A few months later Mott would mail the host that painting—a gift of art in exchange for hospitality.

In his seven years of touring Mott has stayed with more than 65 hosts, each with his own routines, beliefs and interests. "It's quirky moving from one household to the next, where people have very different ways of living, different schedules," he says. "I almost always feel disoriented and a little on edge for the first 24 hours. During that time people seem unreasonable and odd."

He has stayed with fellow Dartmouth alums, such as Larry Stifler '63, Ingeborg Sacksen '84, DMS '91, and Edie Farwell '83 and Jay Mead '82. He has also stayed with strangers. Some of his hosts are fellow artists, while some don't know the difference between an easel and a palette. Some leave Mott almost entirely to his own devices, while others make requests.

"On my first tour I had a host in the middle of nowhere, Illinois, who thought that the surroundings of cornfields and soybean fields were too boring, so he took me half an hour away to paint trees," Mott recalls. "He took me to this park that looked like western New York, where I'm from." Not exactly what Mott was hoping for.

"I saw something different through his eyes," says Norma Marciano, who hosted Mott several years ago in her Las Vegas home. Mott painted her pool area and garden, and Marciano chose to keep a painting of her pool deck chair. "He sees a lot of things that we, as ordinary, non-artist people, do not see," she says.

His artist hosts also appreciate his vision. Rebecca Crowell, a painter from Osseo, Wisconsin, housed him on his latest tour. They met online through a forum for painters, and she decided to contact him when the forum moderator sent out a message detailing Mott's project. She and her husband chose to keep a painting Mott did of their side yard. "It was just a very nice feeling of our place in that painting, and we both liked it," she says.

When Mott stayed at the apartment of friend John Marvel '82 in Cody, Wyoming, Marvel was not able to be there. That led to Mott s first experiences bartering art for food.

"The first two paintings were of basically equal value, but they went into two totally different systems—the gift system and the market/gallery system," Mott says. "It sort of defines the different worlds."

During his senior year at Dartmouth Mott was quoted in the The D saying that after graduation he hoped to be a community artist—to paint for the community, wherever he lived. "I was very idealistic and naive," Mott says. He has since wised up, earning a masters in painting from the University of Michigan and another bachelor s in water resources from SUNY Brockport. When he is not on the road touring for his lAP Mott earns his living part-time as an environmental consultant in Rochester, New York, and sells paintings on the side. Although he may not be as naive as he was in his 20s, his idealism and passion for art clearly remain.

"Going out on the road, paradoxically, gives me a supportive community," Mott muses. "It's a provisional community. My hosts get a lot out of it and I get a lot of out of it. It's a micro-culture, spread out all over the country, where I can practice my vocation."

Portrait of the Artsst "The people I stay withhave a sense of the artist's vision—they'reCurious to see what I'llmake out of their world,"says the painter, heredoing his part to earnhis keep last fall inBozeman, Montana.(On preceding page aresamples of Mott's workfrom Arizona toMaine—and his paint-spattered boots.)

"THE PROJECT INVOLVED A LOT OF THINGS THAT I'M REALLY UNCOMFORTABLE DOING," MOTT SAYS, "LIKE TRAVELING."

CAROLYN KYLSTRA, aformer DAM intern, is working at Men's Health

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

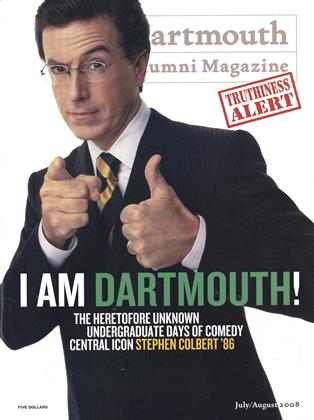

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July | August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Feature

FeatureOn Patrol

July | August 2008 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2008 By John Kemp Lee '78 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLearning Experience

July | August 2008 By Susan Marine

Carolyn Kylstra ’08

-

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May/June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticlePlanet Dartmouth

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

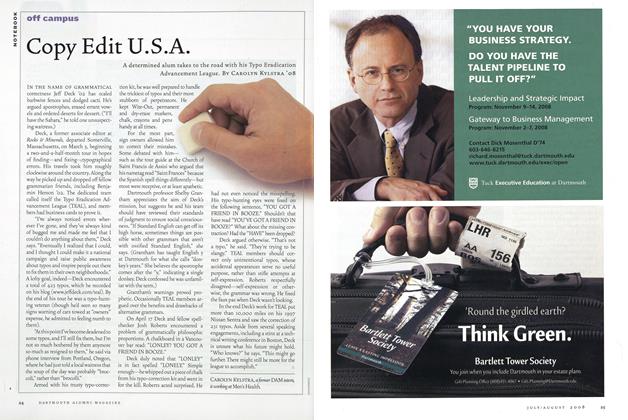

Off Campus

Off CampusCopy Edit U.S.A.

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

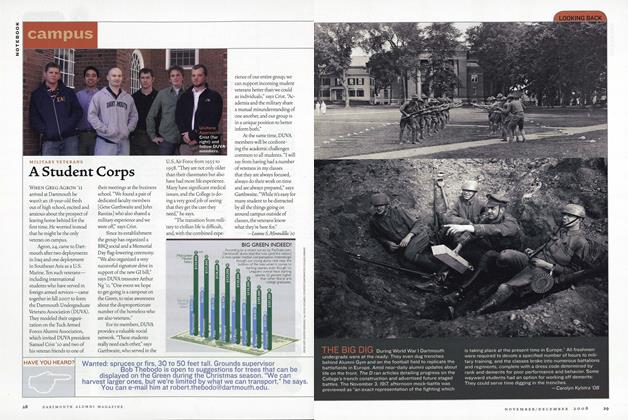

ArticleLOOKING BACK

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

STUDENT LIFE

STUDENT LIFEEverybody In!

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

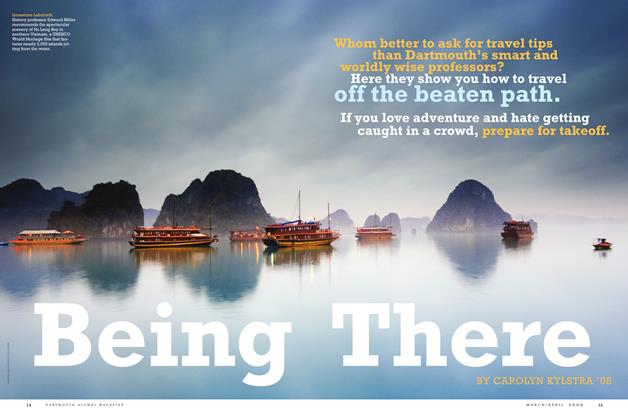

COVER STORY

COVER STORYBeing There

Mar/Apr 2009 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

Features

-

Feature

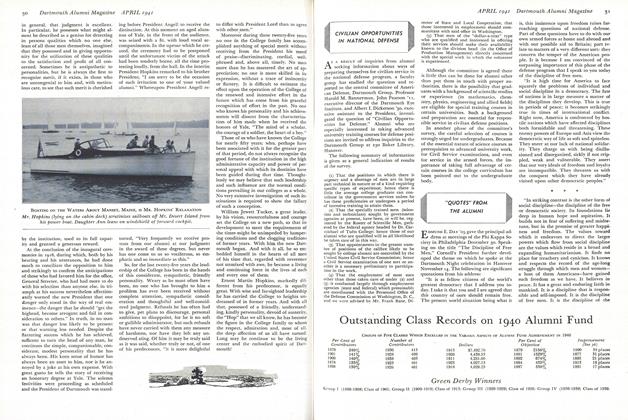

FeatureOutstanding Class Records on 1940 Alumni Fund

April 1941 -

Feature

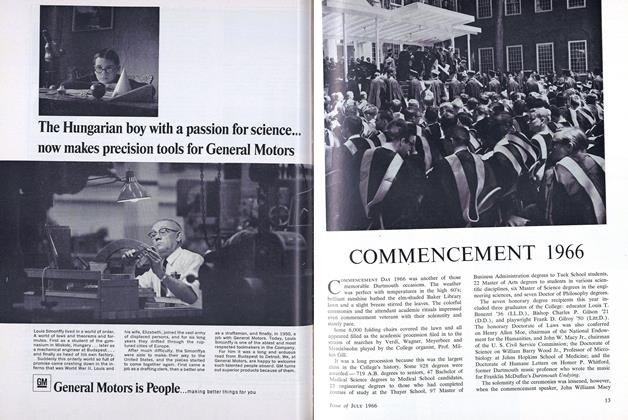

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1966

JULY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

JUNE 1973 -

Feature

FeatureNine From '84

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeachers in the Grand Manner

APRIL 1991 By DEBORAH SCHUPACK '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RESTORE THE ENVIRONMENT

Sept/Oct 2001 By THEODOR "DR. SEUSS" GEISEL '25