The Hole Truth

Clinton Gardner ’44—and his Army helmet—barely survived D-Day.

MAY | JUNE 2014 RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14Clinton Gardner ’44—and his Army helmet—barely survived D-Day.

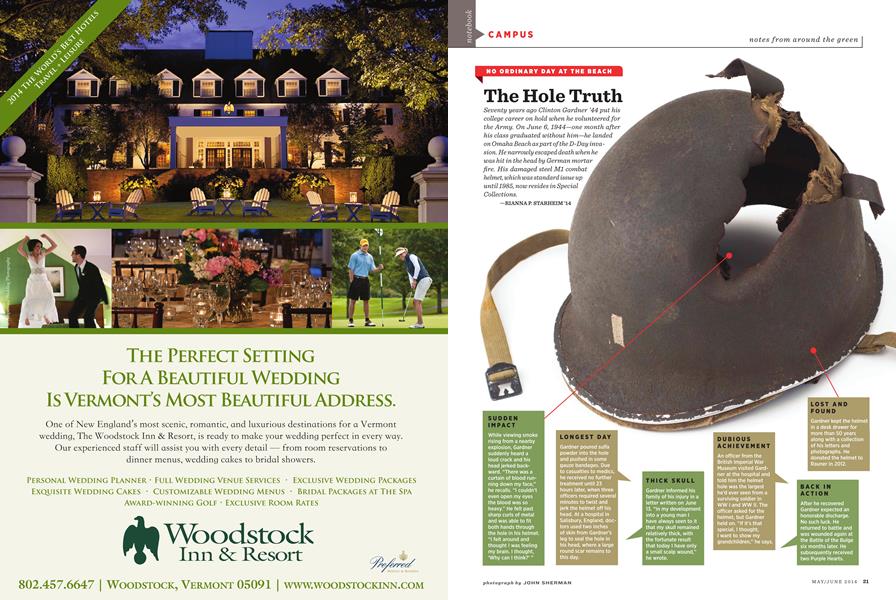

MAY | JUNE 2014 RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14Seventy years ago Clinton Gardner ’44 put his college career on hold when he volunteered for the Army. On June 6, 1944—one month after his class graduated without him—he landed on Omaha Beach as part of the D-Day invasion. He narrowly escaped death when he was hit in the head by German mortar fire. His damaged steel M1 combat helmet, which was standard issue up until 1985, now resides in Special Collections.

SUDDEN IMPACT While viewing smoke rising from a nearby explosion, Gardner suddenly heard a loud crack and his head jerked back- ward. “There was a curtain of blood running down my face,” he recalls. “I couldn’t even open my eyes the blood was so heavy.” He felt past sharp curls of metal and was able to fit both hands through the hole in his helmet. “I felt around and thought I was feeling my brain. I thought, ‘Why can I think?’”

lo n G E st day Gardner poured sulfa powder into the hole and pushed in some gauze bandages. Due to casualties to medics, he received no further treatment until 23 hours later, when three officers required several minutes to twist and jerk the helmet off his head. At a hospital in Salisbury, England, doc- tors used two inches of skin from Gardner’s leg to seal the hole in his head, where a large round scar remains to this day.

t h i c k s ku l l Gardner informed his family of his injury in a letter written on June 13. “In my development into a young man I have always seen to it that my skull remained relatively thick, with the fortunate result that today I have only a small scalp wound,” he wrote.

d u b i o u s ac h i E V E m E n t An officer from the British Imperial War Museum visited Gard- ner at the hospital and told him the helmet hole was the largest he’d ever seen from a surviving soldier in WW I and WW II. The officer asked for the helmet, but Gardner held on. “If it’s that special, I thought, I want to show my grandchildren,” he says.

lost a n d Fo u n d Gardner kept the helmet in a desk drawer for more than 50 years along with a collection of his letters and photographs. He donated the helmet to Rauner in 2012.

bac k i n ac t i o n After he recovered Gardner expected an honorable discharge. No such luck. He returned to battle and was wounded again at the Battle of the Bulge six months later. He subsequently received two Purple Hearts. —Rianna P. Starheim ’14twoPurpleHearts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureZoology

May | June 2014 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD HAIR

May | June 2014 By Ana Sofia De Brito ’12 -

Feature

FeatureSEEKING TO BE WHOLE

May | June 2014 By Shannon Joyce Prince ’09 -

Feature

FeatureONE PLUS ONE EQUALS THREE

May | June 2014 By Yuki Kondo-Shah ’07 -

Sports

SportsOut of Nowhere

May | June 2014 By SARAH LORGE BUTLER -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEConfluences

May | June 2014 By MICHAEL CALDWELL ’75

RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14

-

Article

ArticleBring on the Funk

MARCH | APRIL 2014 By Rianna P. Starheim ’14 -

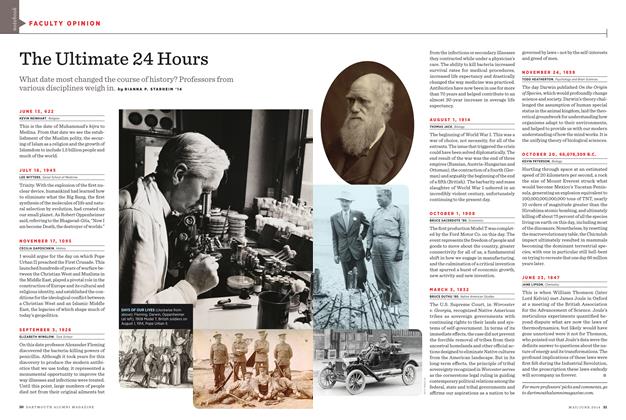

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Ultimate 24 Hours

MAY | JUNE 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

Feature

FeatureOff the Beaten Path

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

FACULTY

FACULTYPoetic Justice

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Truth Is Out There

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

pursuits

pursuitsWristy Business

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By Rianna P. Starheim ’14

CAMPUS

-

Campus

Campus1

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

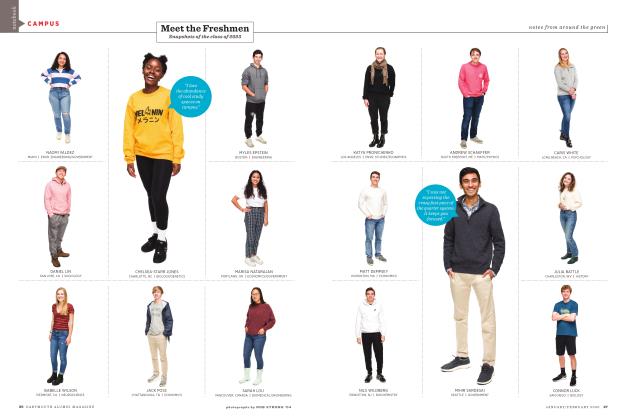

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMeet the Freshmen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSAT A GLANCE

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSCAMPUS CONFIDENTIAL

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 -

Campus

CampusA New VP for Alumni Relations

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By ABIGAIL DRACHMAN-JONES ’03 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSWhat’s New

July/August 2012 By Lee Michaelides