IN KANDAHAR IN 2005, SWIFT WAS woken by a group of young men pointing Kalashnikovs at him. "All I could say was, 'Good morning, brother, how are you?' " he recalls. His interpreter handled the situation. "They put their guns away, and 10 minutes later we're all sitting on the floor eating like nothing had happened."

Swift put himself in similarly tense situations for the next seven years as he conducted academic field research in combat zones across the globe, interviewing the people who lived in affected areas. He traveled to Afghanistan, Dagestan on the Chechen border, the West Bank and Yemen. The research informed a master's and Ph.D. in international studies from Cambridge University and a J.D. from Georgetown.

Today he's an adjunct professor of national security studies at Georgetown, an attorney at Foley & Lardner, a frequent media commentator on issues of national security and terrorism and a term member on the Council of Foreign Relations. Understanding what drives terror—and which groups are threats, which groups aren't—has given him a voice in policy discussions. "You can know everything in the world about a particular subject, but if you can't help a policymaker implement policy, that academic knowledge isn't terribly useful," says Swift. "On the flipside, if you're just a lawyer and all you know is process, you don't have any substance to share."

His objective: To create a predictive model of behavior for how local indigenous insurgencies interact with Al Qaeda. He wants to give the government—and the American people—the language needed to understand the parameters of a conflict. "I've had too many students get blown up or have some catastrophic injury with- out knowing who the enemy was, without knowing what the plan was and what the end game was," he says.

The national security expert examines what brings Islamic militants together—and what could drive them apart.

"I've had too many studentsget blown up without knowingwho the enemy was

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

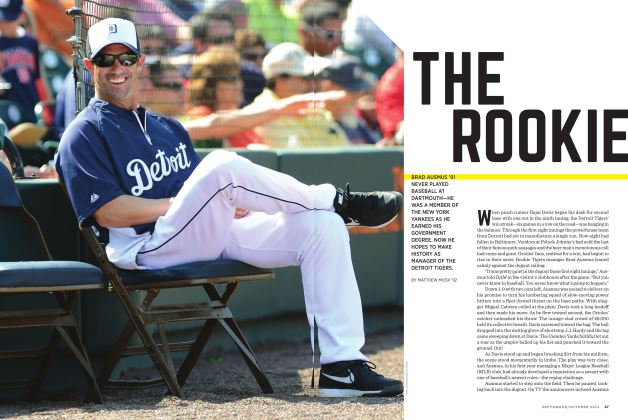

FEATUREThe Rookie

September | October 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

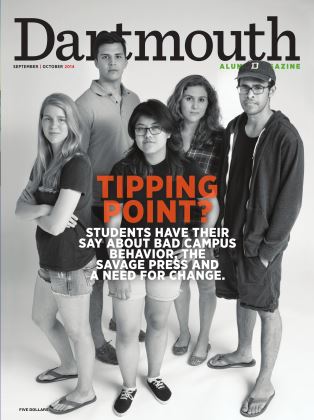

COVER STORY

COVER STORYWhat’s Going On Here?

September | October 2014 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

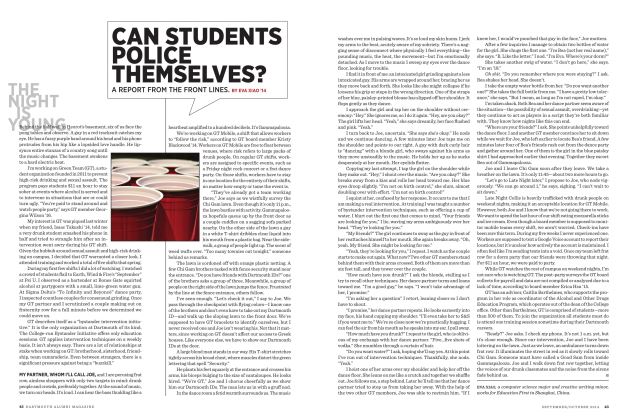

FeatureCan Students Police Themselves?

September | October 2014 By EVA XIAO ’14 -

Feature

FeatureOff the Beaten Path

September | October 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2014 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

September | October 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY

Carolyn Kylstra ’08

-

Article

ArticleSTARTUP STUDENTS

May/June 2007 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Sports

SportsSwimming Lessons

Nov/Dec 2007 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleFor Women Only

Jan/Feb 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May/June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleLost and Found

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleLOOKING BACK

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

Article

-

Article

ArticlePOETS AND MORE POETS

DECEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleTrustee nominations sought

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 -

Article

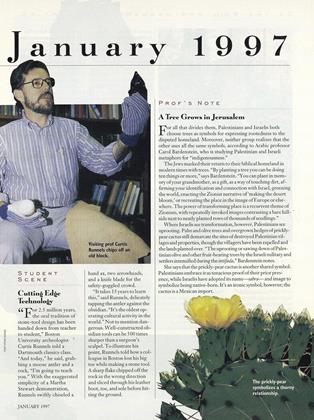

ArticleA Tree Grows in Jerusalem

JANUARY 1997 -

Article

ArticleSPRING SPORTS

APRIL 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticlePotato Head

December 1987 By Jay Fogarty '88 -

Article

ArticleCape Cod

OCTOBER 1962 By ROBERT M. BURRILL ’50