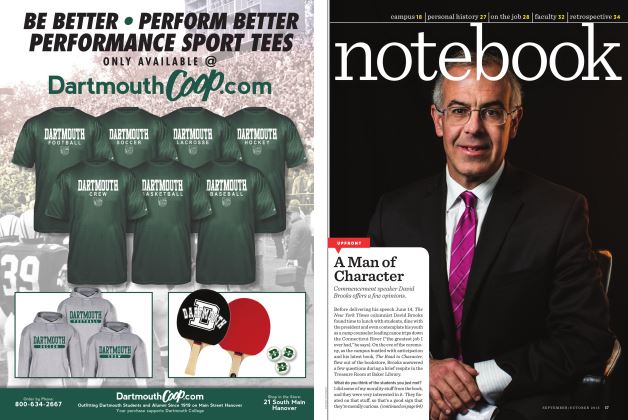

Commencement speaker David Brooks offers a few opinions.

Before delivering his speech June 14, The New York Times columnist David Brooks found time to lunch with students, dine with the president and even contemplate his youth as a camp counselor leading canoe trips down the Connecticut River (“the greatest job I ever had,” he says). On the eve of the ceremo- ny, as the campus bustled with anticipation and his latest book, The Road to Character, flew out of the bookstore, Brooks answered a few questions during a brief respite in the Treasure Room at Baker Library.

What do you think of the students you just met? I did some of my morality stuff from the book, and they were very interested in it. They fix- ated on that stuff, so that’s a good sign that they’re morally curious.

Recently you’ve written quite a bit about col- lege students. Where do you get your take on the campus scene? I teach two classes at Yale, so I know a lot of students there. Also I visit 10 to 15 colleges a year.

You’ve taken parents to task for failing to tran- sition their children to adulthood. Is that true in the Ivy League? Yes. Because I teach at Yale a lot of my knowledge, but not exclusively, comes from elite institutions. I go to community colleges too, and everything in between, but a lot of the maladies I see, especially as far as parents who are not letting go, that’s probably more true at the elite universities than anywhere else.

Do you feel you were let go when you went to the University of Chicago? Back then my parents had no choice. That was pre-cellphone, so I would call in once a term, you know. Cellphones are the thing that’s made the big difference.

The course you teach is about humility, cor- rect? Yes. Now that I’ve got the book out I prob- ably won’t teach it again. The best compli- ment I got was from a student who took the class—it’s moral philosophy—and he said at the end, “Your class has made me a lot sadder.” I consider that a win.

What do you think of the whole microaggres- sion phenomenon that many students seem to embrace? I just think it’s overly sensitive. People are going to behave badly, people are going to behave well. But sometimes there’s going to be insult. Roll with it. That’s my basic attitude. That’s not to excuse racism and sexism and stuff—when it happens on a significant scale obviously that needs to be punished. But I guess my problem is making everybody’s feelings an absolute truth, and this means you can never say anything that hurts somebody’s feelings. I think it has had this effect of chilling life and conversation on campus a bit.

What’s your sense of the near-term future of the liberal arts? Obviously to me the big problem with the liberal arts, and the reason they’re still los- ing energy and money and students, is that they wandered from their lane. The lane of the liberal arts is emotional and social and moral growth, and unfortunately they got too much into race, class and gender, which are social issues. So they wandered into the spheres of sociology and political science and they lost their core thing. To me, students, like anybody else, are wor- rying about relationships. They’re curious about their own emotions. The liberal arts should be dealing with them, helping them identify and educate their emotions.

Are the liberal arts heading back into the prop- er lane? I think individual people are, but I think there’s still a lot of veering off.

What can be done about the incredible cost of getting a college degree these days? Well the easy thing is to get rid of half the administrators. But I guess when you have all these federal requirements, you’ve just got to have a lot of administrators. The other obvious answer is to do a lot more online. But, frankly, I think online is going to come to Western Kentucky University. I don’t think online is really going to change Dartmouth much.

If you were named president of Dartmouth, what would be among your top priorities? I think one of the crucial decisions in life is who you marry, so I would have a lot of courses on how to think about that. Of course the students are way too young [to marry], but you could have the sociol- ogy of marriage, the religion of marriage, the psychology of marriage, literature of marriage, and I just think it would be a good grounding so when seven or eight years hence the students start thinking about this decision they’ll say, “Oh yeah, I learned something about that. I can go back to that.”

Some folks here would probably prefer that you tackle the campus parking problem. [Laughs] Well, this is a nationwide prob- lem. Every campus has parking problems.

You wrote a “humility code” for your new book. How could you instill those virtues into a college curriculum? I think mostly we learn through habits and biography, and so I would love to see more classes in biography: learning from people and then discussing their lives. I believe in the Common Core, and I think I became familiar with a lot of those ideas just in the reading of Hobbes, Aristotle, Plato, Gospel of St. John, the Book of Exodus. A college can’t really dictate a moral code to students but it can give them familiarity with ones and then they’ll sign up. Or not.

Do you give many commencement speeches? I usually do one a year. I’d like to do one four-year institution a year and one com- munity college, but the community colleges don’t ask me that much. So I haven’t done one in a couple years. Isn’t it hard to come up with something new to say, something that hasn’t already been said? It is hard. It’s a very challenging form.

Do you remember your commencement speaker at the University of Chicago? Of course not. No one does. We don’t really have guest speakers there, but rather a fac- ulty member who would talk to us.

How do you juggle all that you do? Do you have a team of helpers and researchers? I have one researcher at the Times. And then I’ve got someone to just help me with my web page. It’s all I do. I don’t go to meet- ings. I have no bosses, really. I ride the train to New Haven a lot so I’ve got a lot of time on the train. I gave up golf. I don’t watch TV that much; I’ll watch on the Internet. So I’ve given up everything but work and leisure.

Why did you give up golf? I figured I could either write books or play golf. I could not do both. It’s a pretty time- consuming sort of deal.

Our readers love book recommendations. What can you suggest? One would be Christian Wiman’s book, My Bright Abyss. It’s about faith, what faith feels like. And I recently read a great bi- ography about Bayard Rustin. And I just recommended to the students that they read Anna Karenina and Middlemarch.

As a former film critic, do you watch many movies? Watching 10 movies a week killed my love of movies, because I could no longer just sink myself into them. They became a job, I had the notebook. I probably go to four or five a year, but I used to get really lost in movies and now I almost never do.

And you were forced to view a lot of bad ones as a critic. And you can’t walk out! You’re stuck there for the whole movie.

Do you follow any sports teams? I’m a big New York Mets fan. That’s my No. 1 team. And to compensate I’m also a Dallas Cowboys fan.

Sandy Alderson, general manager of the Mets, is a Dartmouth alum, class of 1969. Oh is he? He’s good at getting pitching. Hit- ting, not so much.

Since you went to the school where fun goes to die, do you ever have any fun? [Laughs] I go out to dinner. I think I go out for meals almost every day, so I socialize.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER STORY

COVER STORYBash Brothers

September | October 2015 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

FEATURE

FEATUREHat Couture

September | October 2015 By HEATHER SALERNO -

FEATURE

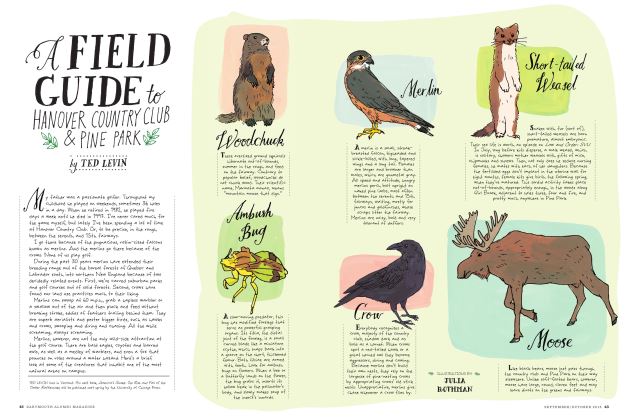

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

September | October 2015 By TED LEVIN -

Feature

Featureclass notes

September | October 2015 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

September | October 2015 By VOSS/REDUX STEPHEN -

Article

ArticleON THE JOB

September | October 2015

Sean Plottner

-

UPFRONT

UPFRONTGatekeeper

MAY | JUNE 2016 By Sean Plottner -

notebook

notebook“Definitely Heartbreaking”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By Sean Plottner -

notebook

notebookSTUDENT LIFE Dorm Project Halted

MAY | JUNE 2022 By Sean Plottner -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSMurder in the Congo

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By Sean Plottner -

notebook

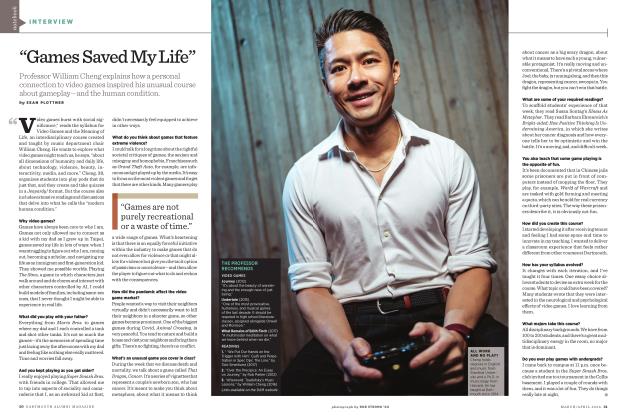

notebook“Games Saved My Life”

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By Sean Plottner -

FEATURES

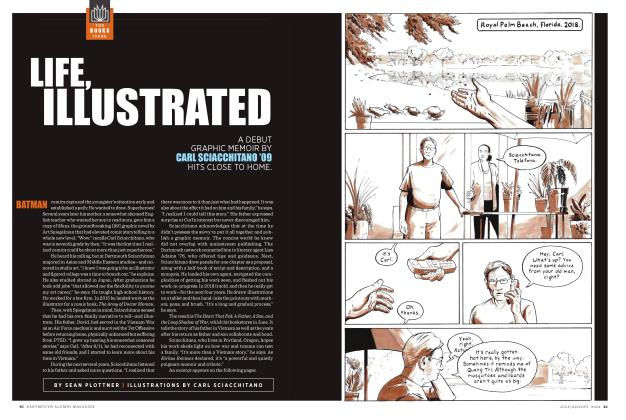

FEATURESLife, Illustrated

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Sean Plottner

Article

-

Article

ArticleMID-WINTER

January 1919 -

Article

ArticleWar-Damaged Ears

March 1946 -

Article

ArticleRural Nominated for Second Trustee Term

March 1951 -

Article

ArticleExperimental and Over-Subscribed.

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleCamp Counselor

Sept/Oct 2005 By Kathryn Levy Feldman -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1974 By VICTOR F. ZONANA'75