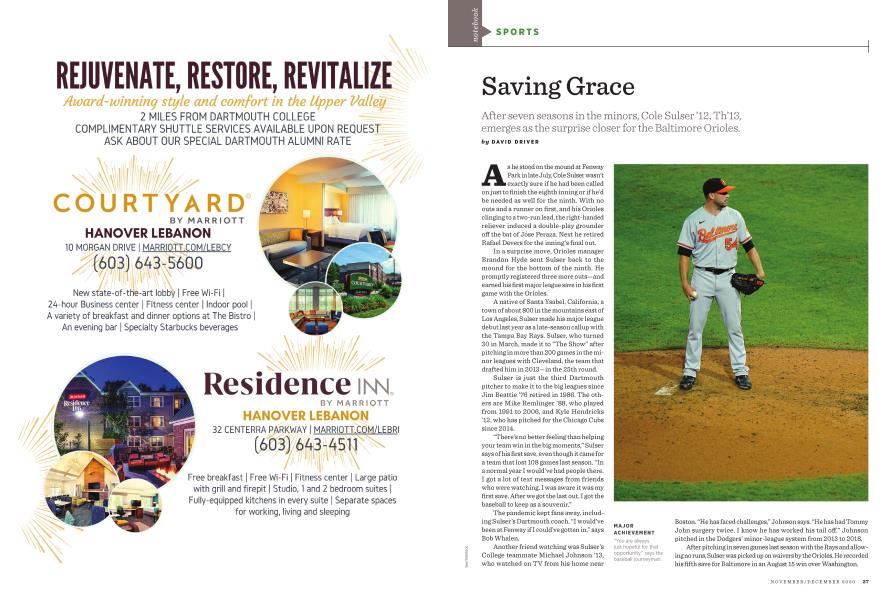

Saving Grace

After seven seasons in the minors, Cole Sulser '12, Th’13, emerges as the surprise closer for the Baltimore Orioles.

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 DAVID DRIVERAfter seven seasons in the minors, Cole Sulser '12, Th’13, emerges as the surprise closer for the Baltimore Orioles.

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 DAVID DRIVERSaving Grace

notebook

SPORTS

After seven seasons in the minors, Cole Sulser '12, Th’13, emerges as the surprise closer for the Baltimore Orioles.

DAVID DRIVER

As he stood on the mound at Fenway Park in late July, Cole Sulser wasn’t exactly sure if he had been called on j ust to finish the eighth inning or if he’d be needed as well for the ninth. With no outs and a runner on first, and his Orioles clinging to a two-run lead, the right-handed reliever induced a double-play grounder off the bat of Jóse Peraza. Next he retired Rafael Devers for the inning’s final out.

In a surprise move, Orioles manager Brandon Hyde sent Sulser back to the mound for the bottom of the ninth. He promptly registered three more outs—and earned his first major league save in his first game with the Orioles.

A native of Santa Ysabel, California, a town of about 800 in the mountains east of Los Angeles, Sulser made his major league debut last year as alate-season callup with the Tampa Bay Rays. Sulser, who turned 30 in March, made it to “The Show” after pitching in more than 200 games in the minor leagues with Cleveland, the team that drafted him in 2013—in the 25th round.

Sulser is just the third Dartmouth pitcher to make it to the big leagues since Jim Beattie ’76 retired in 1986. The others are Mike Remlinger ’88, who played from 1991 to 2006, and Kyle Hendricks T2, who has pitched for the Chicago Cubs since 2014.

“There’s no better feeling than helping your team win in the big moments,” Sulser says of his first save, even though it came for a team that lost 108 games last season. “In a normal year I would’ve had people there. I got a lot of text messages from friends who were watching. I was aware it was my first save. After we got the last out, I got the baseball to keep as a souvenir.”

The pandemic kept fans away, including Sulser’s Dartmouth coach. “I would’ve been at Fenway if I could’ve gotten in,” says Bob Whalen.

Another friend watching was Sulser’s College teammate Michael Johnson T3, who watched on TV from his home near Boston. “He has faced challenges,” Johnson says. “He has had Tommy John surgery twice. I know he has worked his tail off.” Johnson pitched in the Dodgers’ minor-league system from 2013 to 2018.

After pitching in seven games last season with the Rays and allowing no runs, Sulser was picked up on waivers by the Orioles. He recorded his fifth save for Baltimore in an August 15 win over Washington.

Coming out of his small southern California high school, Sulser had limited Division I options. “Academics was always something I valued. My mother is an elementary school principal,” he says. “Dartmouth was a perfect fit for me. Even without baseball, it is an amazing institution.”

Whalen learned about Sulser following the pitcher’s junior year of high school. “He pitched 101 innings in high school, a stunning amount,” says Whalen, who started coaching at Dartmouth in 1990. “I wanted to try and protect him. He would beg to throw every day.” Two things stood out about Sulser, according to his former coach: the ability to pitch to both sides of the plate and a penchant for getting hitters to swing through his fastball.

Sulser started eight games, finished 5-3, and had an ERA of 2.52 in nine appearances for the Big Green during his redshirt final season in 2013. After being drafted, he entered the decidedly unglamorous life of a minor leaguer—full of long bus rides and second-rate hotels.

“Several factors kept me going,” says Sulser. “One was my love for the sport of baseball [and knowing] it’s going to come to an end for all of us one day. Also, I felt secure with the education I got at Dartmouth. I could pursue baseball without jeopardizing everything in my future.” Sulser earned two degrees, one in public policy, the other in mechanical engineering.

When baseball shut down in March due to Covid-19, Sulser and his brother, Beau T6, who is a promising pitcher in the Pittsburgh Pirates system, trained in southern California. “He’s an amazing big brother and role model,” says Beau. The brothers also help younger players decide where to attend college through their Sigma Sports Consulting.

Sulser is still paying off college loans but is buoyed by the annual major league minimum salary of about $563,000 (prorated this year because of the reduced schedule) after making just a few thousand dollars per month in the minors.

Now he is one of 30 closers in the majors.

“He’s a high-character kid,” Hyde said of Sulser in July. “I don’t know him very well, but I do know in our short time with him he’s a tough kid.”

DAVID DRIVER has covered the Baltimore Orioles for more than 25 years. He has contributed to The Washington Post, The Washington Times, Associated Press, The Boston Globe, and MLB.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

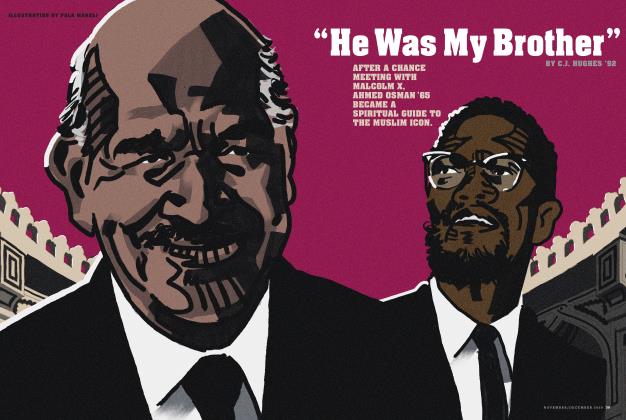

Feature“He Was My Brother”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureTruth Be Told

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Features

FeaturesRising Star

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

notebook

notebookTales From the Trail

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By DAVID LIGHTMAN -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1991

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Deb Karazin Owens -

Interview

Interview“Your Brain Is Wrong”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER

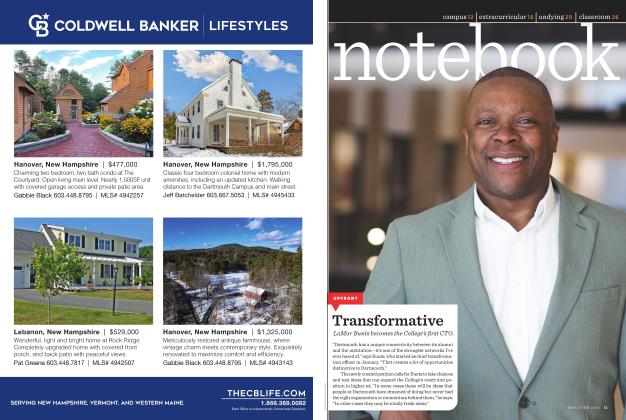

Notebook

-

notebook

notebookEUREKA!

JULY | AUGUST 2017 -

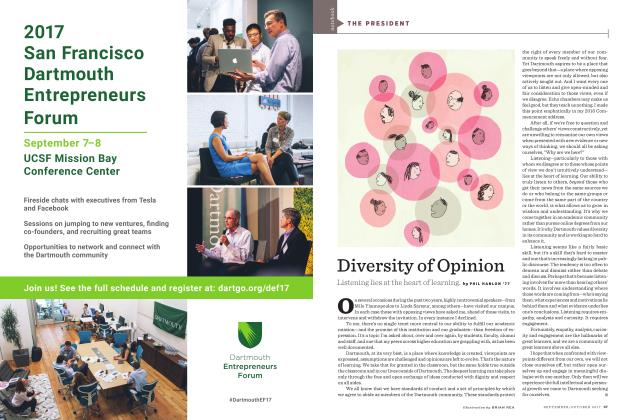

notebook

notebookTransformative

MAY | JUNE 2023 -

notebook

notebookEUREKA!

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Emily Sun ’22, Elizabeth Janowski ’21 -

notebook

notebookLOOK WHO'S TALKING

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By George M. Spencer -

notebook

notebookDiversity of Opinion

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By PHIL HANLON -

notebook

notebookSpice of Life

MAY | JUNE 2024 By PRIYA KRISHNA '13