Frozen Fieldwork

David Clemens-Sewall ’14, Th’18, describes working in the Arctic on a momentous scientific expedition.

MAY | JUNE 2021 Svati Kirsten Narula ’13David Clemens-Sewall ’14, Th’18, describes working in the Arctic on a momentous scientific expedition.

MAY | JUNE 2021 Svati Kirsten Narula ’13The largest polar expedition in history, MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate), took place during 2019-2020 aboard the icebreaker Polarstern, Germany’s largest research vessel. The goal was for more than 300 scientists from 20 countries to conduct hundreds of research projects and amass data on conditions in the Arctic, leading to a better understanding of climate change there. David Clemens-Sewall, a Ph.D. student who majored in chemistry and earth sciences as an undergrad and had spent several seasons in Antarctica for his thesis, was one of several Dartmouth-affiliated researchers who participated.

What kind of data were you tasked with collecting on this expedition?

The goal was to understand how snow and ice are changing in the Arctic sea. Most of the measurements I was making were direct measurements of how much ice and snow is there, how is it distributed spatially, and how is it changing through time. The major tool I used was a terrestrial laser scanner, or a LiDAR, which is basically a rotating laser that I used to map the surface of the snow. You can make 3-D maps and then, by repeatedly making these maps through time, you see how the snow surface or the ice surface is changing.

Was there time for fun, too?

Occasionally. It’s sort of an all-encompassing thing where you wake up, go out on the ice, work all day, and then process data or fix equipment in the evening and get ready to do it again. But we had lots of time to relax on the transit to and from the boat. And we usually tried to take Sunday mornings off unless there’d been bad weather the previous three days.

What qualifies as bad weather in the Arctic?

The big challenge is visibility. It’s a significant safety problem if you can’t see. Especially when you get low clouds, the sunlight is all diffuse, the wind starts blowing, and the snow really picks up, you can get to the point where you just can’t see where you’re walking. I don’t think we ever had any limitations on temperature. I think we were supposed to not work outside if it got below minus-50 Fahrenheit, but the coldest it got was around minus-42. We did occasionally have issues where, because the ice was fracturing and moving around, it would push the ship in such a way that you couldn’t disembark because the gangplank could no longer reach over.

“You wake up, go out on the ice, work all day....The coldest it got was around minus-42.”

Could you hear the ice moving when you were onboard the Polarstern?

Oh, yeah. Especially down in the hold, where the gym was. If you were in the gym, you’d hear it sort of crunching back and forth.

Did you see any polar bears?

Just one. They like to hang out where the ice is more broken up. Where we were, it was moving a lot, but it was still 95-percent ice.

Of all the data that you collected with MOSAiC, how much of it is immediately useful?

As far as scientific utility and increasing our capacity for understanding the system, a lot of it. I plan to have something published soon. One of the real strengths of MOSAiC is that I was surrounded by other scientists also collecting data on different processes that interact. In the coming year or two a lot of the data will be used in collaborations that haven’t been possible before.

What is one thing that you wish people from other fields understood better about your field?

Realizing how much we have to offer each other, in terms of things we know and the tools that we have. For example, although I study snow and sea ice, a lot of the tools I’m using were developed in the medical imaging community. I have no doubt that there are innovative ways of not only analyzing data, but also communicating results, spreading information, doing outreach, all that stuff, that people in other fields have put a lot of work into, that would be really valuable for us to take advantage of.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURES

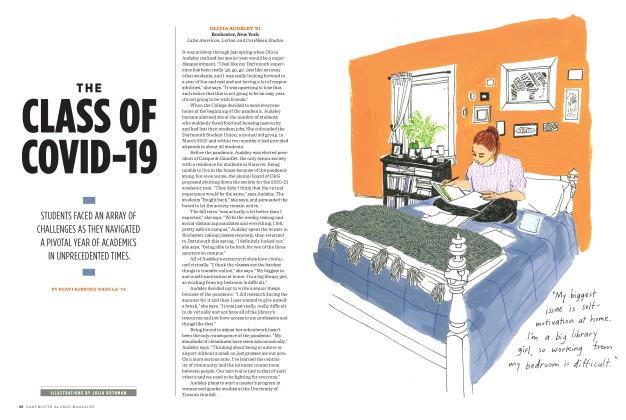

FEATURESThe Class of Covid-19

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

INTERVIEW

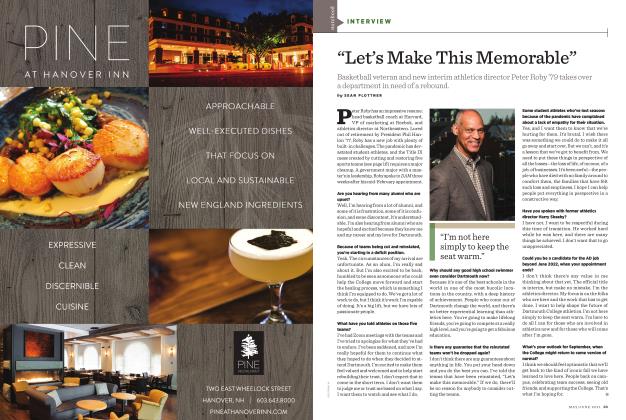

INTERVIEW“Let’s Make This Memorable”

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Sean Plottner -

FEATURES

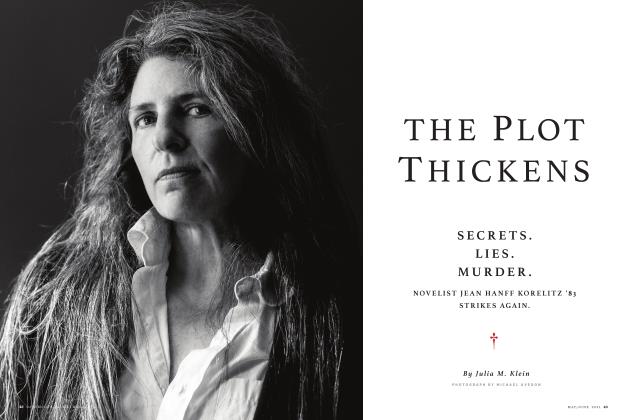

FEATURESThe Plot Thickens

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Julia M. Klein -

FEATURES

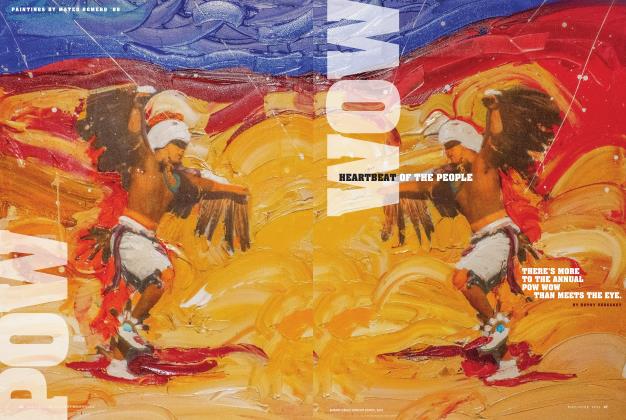

FEATURESHeartbeat of the People

MAY | JUNE 2021 By BETSY VERECKEY -

FEATURES

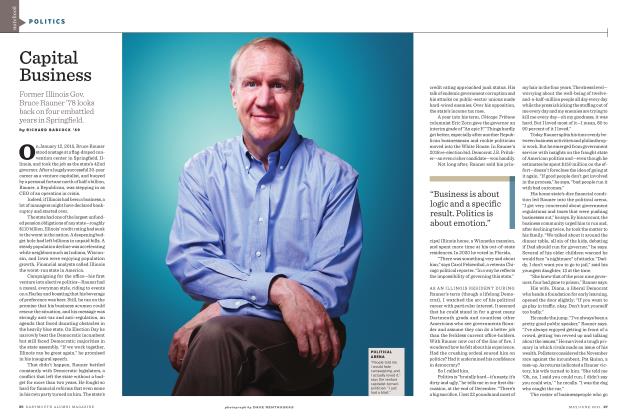

FEATURESCapital Business

MAY | JUNE 2021 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

notebook

notebookOn the Watch

MAY | JUNE 2021 By CHARLOTTE GROSS ’16

Interviews

-

Interview

InterviewHomeward Bound

JULY | AUGUST 2021 -

Interview

Interview“A Failure to Dig Deeper”

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By ABIGAIL JONES ’03 -

Interviews

InterviewsLook Who’s Talking

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By Anne Bagamery ’78 -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

MAY | JUNE 2020 By Betsy Vereckey -

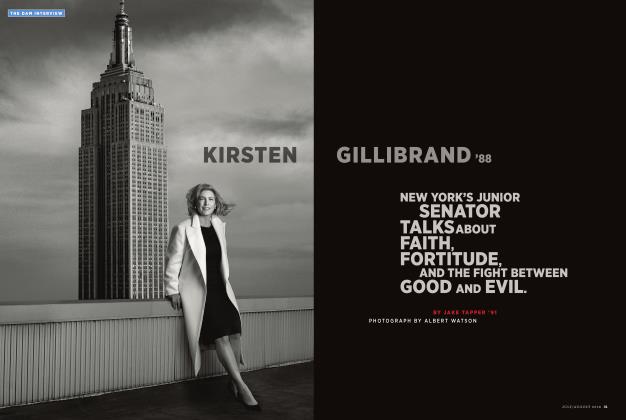

The DAM Interview

The DAM InterviewKirsten Gillibrand ’88

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEW2 Of A Kind

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 By Jake Tapper ’91

Svati Kirsten Narula ’13

-

notebook

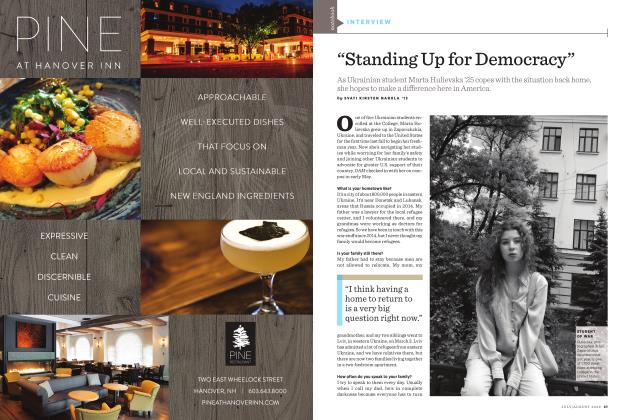

notebook“Standing Up for Democracy”

JULY | AUGUST 2022 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

notebook

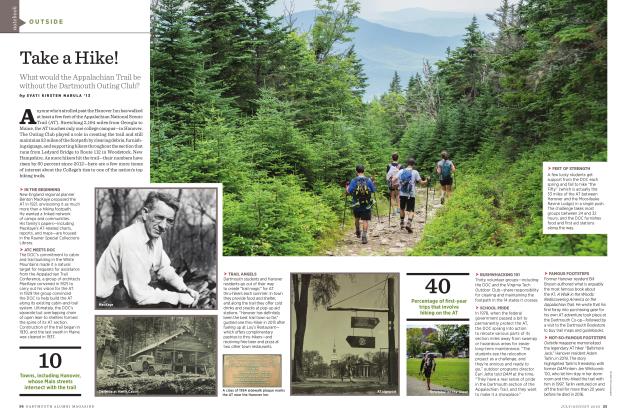

notebookTake a Hike!

JULY | AUGUST 2023 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

Features

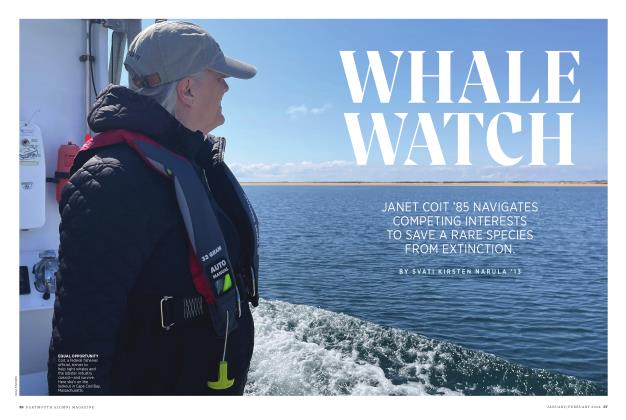

FeaturesWhale Watch

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

CLASSNOTES

CLASSNOTES2013

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES2013

MAY | JUNE 2025 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES2013

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13

Interviews

-

Interview

InterviewMathias Wins AoA Election

Sept/Oct 2008 -

Interviews

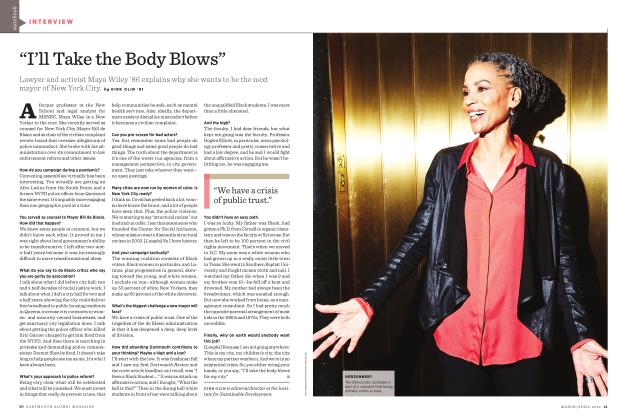

Interviews“I’ll Take the Body Blows”

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By DIRK OLIN '81 -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

SEPTEMBER 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

Interview“Doing Your Own Thing”

July/August 2001 By Randy Stebbins ’01 -

INTERVIEW

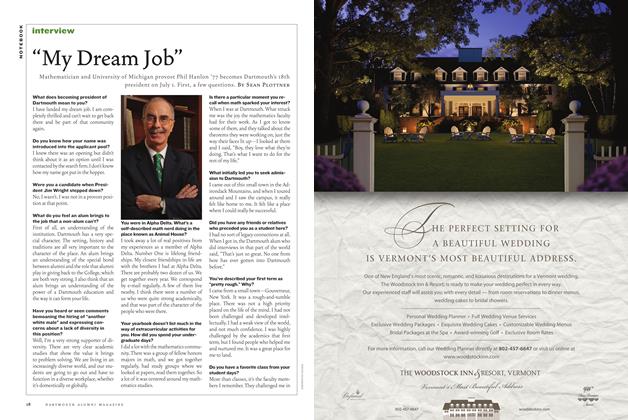

INTERVIEW“My Dream Job”

Jan/Feb 2013 By Sean Plottner -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Let’s Make This Memorable”

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Sean Plottner