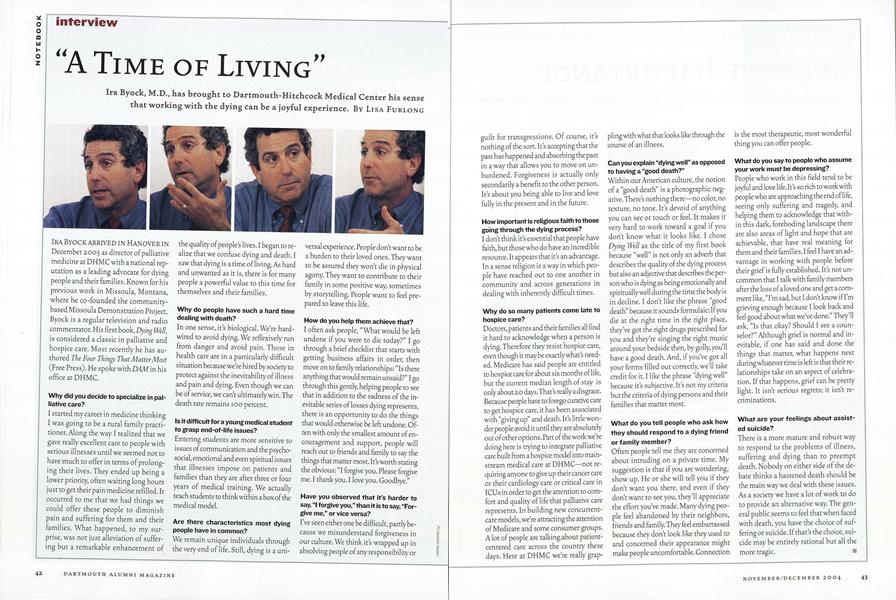

“A Time of Living”

Ira Byock, M.D., has brought to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center his sense that working with the dying can be a joyful experience.

Nov/Dec 2004 Lisa FurlongIra Byock, M.D., has brought to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center his sense that working with the dying can be a joyful experience.

Nov/Dec 2004 Lisa FurlongIra Byock, M.D., has brought to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center his sense that working with the dying can be a joyful experience.

IRA BY OCK ARRIVED IN HANOVER IN December 2003 as director of palliative medicine at DHMC with a national reputation as a leading advocate for dying people and their families. Known for his previous work in Missoula, Montana, where he co-founded the community- based Missoula Demonstration Project, Byock is a regular television and radio commentator. His first book, Dying Well, is considered a classic in palliative and hospice care. Most recently he has authored The Four Things That Matter Most (Free Press). He spoke with DAM in his office at DHMC.

Why did you decide to specialize in palliative care?

I started my career in medicine thinking I was going to be a rural family practitioner. Along the way I realized that we gave really excellent care to people with serious illnesses until we seemed not to have much to offer in terms of prolonging their lives. They ended up being a lower priority, often waiting long hours just to get their pain medicine refilled. It occurred to me that we had things we could offer these people to diminish pain and suffering for them and their families. What happened, to my surprise, was not just alleviation of suffering but a remarkable enhancement of the quality of peoples lives. I began to realize that we confuse dying and death. I saw that dying is a time of living. As hard and unwanted as it is, there is for many people a powerful value to this time for themselves and their families.

Why do people have such a hard timedealing with death?

In one sense, it's biological. We're hardwired to avoid dying. We reflexively run from danger and avoid pain. Those in health care are in a particularly difficult situation because we're hired by society to protect against the inevitability of illness and pain and dying. Even though we can be of service, we can't ultimately win. The death rate remains 100 percent.

Is it difficult for a young medical studentto grasp end-of-life issues?

Entering students are more sensitive to issues of communication and the psychosocial, emotional and even spiritual issues that illnesses impose on patients and families than they are after three or four years of medical training. We actually teach students to think within a box of the medical model.

Are there characteristics most dyingpeople have in common?

We remain unique individuals through the very end of life. Still, dying is a universal experience. People don't want to be a burden to their loved ones. They want to be assured they won't die in physical agony. They want to contribute to their family in some positive way, sometimes by storytelling. People want to feel prepared to leave this life.

How do you help them achieve that?

I often ask people, "What would be left undone if you were to die today?" I go through a brief checklist that starts with getting business affairs in order, then move on to family relationships: "Is there anything that would remain unsaid?" I go through this gently, helping people to see that in addition to the sadness of the inevitable series of losses dying represents, there is an opportunity to do the things that would otherwise be left undone. Often with only the smallest amount of encouragement and support, people will reach out to friends and family to say the things that matter most. It's worth stating the obvious: "I forgive you. Please forgive me. I thank you. I love you. Goodbye."

Have you observed that it's harder tosay, "I forgive you," than it is to say, "Forgive me," or vice versa?

I've seen either one be difficult, partly because we misunderstand forgiveness in our culture. We think it's wrapped up in absolving people of any responsibility or guilt for transgressions. Of course, it's nothing of the sort. It's accepting that the past has happened and absorbing the past in a way that allows you to move on unburdened. Forgiveness is actually only secondarily a benefit to the other person. It's about you being able to live and love fully in the present and in the future.

How important is religious faith to thosegoing through the dying process?

I don't think it's essential that people have faith, but those who do have an incredible resource. It appears that it's an advantage. In a sense religion is a way in which people have reached out to one another in community and across generations in dealing with inherently difficult times.

Why do so many patients come late tohospice care?

Doctors, patients and their families all find it hard to acknowledge when a person is dying. Therefore they resist hospice care, even though it maybe exactly what's needed. Medicare has said people are entitled to hospice care for about six months of life, but the current median length of stay is only about 20 days.That's really a disgrace. Because people have to forego curative care to get hospice care, it has been associated with "giving up" and death. It's little wonder people avoid it until they are absolutely out of other options. Part of the work we're doing here is trying to integrate palliative care built from a hospice model into mainstream medical care at DHMC—not requiring anyone to give up their cancer care or their cardiology care or critical care in ICUs in order to get the attention to comfort and quality of life that palliative care represents. In building new concurrentcare models, we're attracting the attention of Medicare and some consumer groups. A lot of people are talking,about patient- centered care across the country these days. Here at DHMC we're really grappling with what that looks like through the course of an illness.

Can you explain "dying well" as opposedto having a "good death?"

Within our American culture, the notion of a "good death" is a photographic negative. There's nothing there—no color, no texture, no tone. It's devoid of anything you can see or touch or feel. It makes it very hard to work toward a goal if you don't know what it looks like. I chose Dying Well as the title of my first book because "well" is not only an adverb that describes the quality of the dying process but also an adjective that describes the person who is dying as being emotionally and spiritually well during the time the body is in decline. I don't like the phrase "good death" because it sounds formulaic: If you die at the right time in the right place, they've got the right drugs prescribed for you and they're singing the right music around your bedside then, by golly, you'll have a good death. And, if you've got all your forms filled out correctly, we'll take credit for it. I like the phrase "dying well" because it's subjective. It's not my criteria but the criteria of dying persons and their families that matter most.

What do you tell people who ask howthey should respond to a dying friendor family member?

Often people tell me they are concerned about intruding on a private time. My suggestion is that if you are wondering, show up. He or she will tell you if they don't want you there, and even if they don't want to see you, they'll appreciate the effort you've made. Many dying people feel abandoned by their neighbors, friends and family. They feel embarrassed because they don't look like they used to and concerned their appearance might make people uncomfortable. Connection is the most therapeutic, most wonderful thing you can offer people.

What do you say to people who assumeyour work must be depressing?

People who work in this field tend to be joyful and love life. It's so rich to work with people who are approaching the end of life, seeing only suffering and tragedy, and helping them to acknowledge that with- in this dark, foreboding landscape there are also areas of light and hope that are achievable, that have real meaning for them and their families. I feel I have an advantage in working with people before their grief is fully established. It's not uncommon that I talk with family members after the loss of a loved one and get a comment like, "I'm sad, but I don't know if I'm grieving enough because I look back and feel good about what we've done." They'll ask, "Is that okay? Should I see a counselor?" Although grief is normal and inevitable, if one has said and done the things that matter, what happens next during whatever time is left is that their relationships take on an aspect of celebration. If that happens, grief can be pretty light. It isn't serious regrets; it isn't recriminations.

What are your feelings about assisted suicide?

There is a more mature and robust way to respond to the problems of illness, suffering and dying than to preempt death. Nobody on either side of the debate thinks a hastened death should be the main way we deal with these issues. As a society we have a lot of work to do to provide an alternative way. The general public seems to feel that when faced with death, you have the choice of suffering or suicide. If that's the choice, suicide may be entirely rational but all the more tragic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

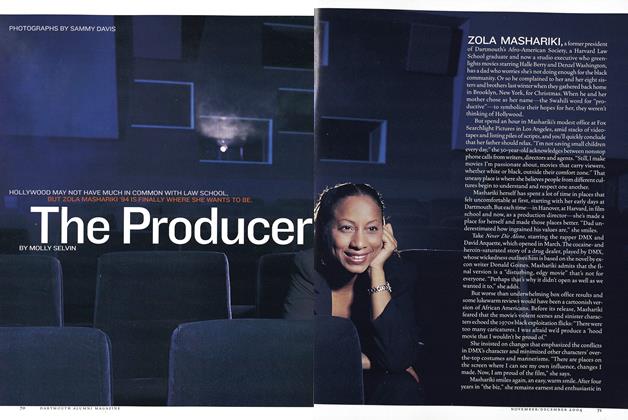

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Sports

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

SEEN AND HEARD

SEEN AND HEARDNewsmakers

November | December 2004

Lisa Furlong

-

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdLaura Ingraham ’85

Nov/Dec 2002 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdDawn Hudson ’79

Mar/Apr 2007 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

July/August 2007 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationNancy (Denny) Kellogg ’78

Nov/Dec 2010 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDPutnam Blodgett ’53, Tu’61

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDJohn White '61

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By LISA FURLONG

Interviews

-

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEWLook Who’s Talking

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By Julia Robitaille ’23 -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

July/August 2007 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

Jan/Feb 2008 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

JULY | AUGUST 2021 By Madison Wilson ’21 -

Interview

Interview“Your Brain Is Wrong”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEWNuclear Reaction

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Sean Plottner