IN September, 1899, Mr. Edward Tuck, of the class of 1862, made a gift to Dartmouth College of the sum of three hundred thousand dollars. This gift, the Amos Tuck Endowment Fund, was to constitute a memorial to his father, the Honorable Amos Tuck, a member of the class of 1835, and a trustee of the College from 1857 to 1866. The terms of the endowment made especial provision for the "establishment of additional professorships within the college proper or in graduate departments." In accordance with this provision, and with the direct approval of the donor, the trustees of the College, on January 19, 1900, created the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance. By this action there were offered to Dartmouth students the opportunities presented by a new associate school, whose object should be to afford advanced specialized training for business as a profession.

The application of the larger portion of this fund to the organization of a graduate school of commerce was the result of a combination of influences. It was not unnatural that a new field of instruction should be added to the curriculum, for one of the marked characteristics of the development of the College during the preceding decade had been a widening of the field of instruction. It was not unnatural that the new field of instruction should be that of higher commercial education, for the gift had been received at a time when courses in commerce were being established in many colleges and universities. The gift had been received at a time, too, when the College had come to realize that it was no longer law, but business, which the majority of graduates took up as a life work. A course in commerce, therefore, would meet the needs of an increasing body of students. Given these conditions, what could be more appropriate than to devote to the establishment of such a course, a fund which had been given by an alumnus out of resources acquired through a successful and honorable career of banking and finance, and which was to constitute a memorial to another alumnus who had been a worthy representative of Dartmouth as a man of affairs? Finally, that the course in commerce should be offered in an associate, graduate school was no less natural, and was perfectly consistent with the opinion that Dartmouth should not attempt to become a university. In explanation of this statement several facts may be presented. The College was at this time considering the advisability of developing graduate work for the sake of the influence it would have in raising the standard of undergraduate work. The establishment of a graduate course in commerce was in line with such a policy. The "Dartmouth idea,"—an idea recognized by that name among educators of the country, and acknowledged to be one which gives Dartmouth an advanced position as a thinker on educational matters—holds that the College should preserve the tradition that its function is to give a liberal and not a specialized training; and that courses which look towards training for special fields of activity should always be presented in a separately organized graduate school. A consideration of this idea will be presented in the course of this article. Again, the College had before it an exponent of this idea, the Thayer School, which had demonstrated its value by its long list of successful graduates. Finally, not one of the commercial courses established by other institutions was of a graduate organization, and Dartmouth in carrying out her peculiar idea would not be duplicating work offered elsewhere. Because of the fact that there was in existence no school of' commerce of graduate rank, there was no school to which Dartmouth graduates could go, analogous to the law schools of Harvard and Columbia. Under these circumstances, it would be impossible for that large body of young men who desire a training for business, to come to Dartmouth,' with the view of securing their special training at another institution after graduation. Therefore, it was necessary that Dartmouth should establish a school of commerce, in order to guarantee that students who should come to her should somewhere and sometime have an opportunity to train for the life work into which an increasing number of them was entering; and it was necessary that that school should be organized as an associate, graduate school, in order to preserve her undergraduate traditions, and to uphold her ideal of the form of organization a group of courses intended to train for a special activity, should take.

It has probably been observed by the reader that the influences which have been described as leading to the establishment of the Tuck School, explain the occasion rather than the fundamental reasons for that establishment. This observation may have given rise in his mind to several queries. Is there any need of schools of higher commercial education in the United States; may not Dartmouth have estimated as vital, a movement that merely represents a passing fancy? Is there anything in the peculiarly Dartmouth plan of graduateschool organization that promises to satisfy in an especial way the demand for trained men on the part of the business world ? These fundamental questions require as thorough a consideration as the limits of this article permit.

Although a school of commerce had been established by the University of Pennsylvania nearly twenty years earlier, it was not until within a few years preceding Mr. Tuck's gift, that the growing belief in the value of industrial training found a general expression in the United States in the organization of schools of higher commercial education. The reasons for the growth of this belief and for its expression at that particular time may be presented briefly as follows. First, it was the result of the growing appreciation of the results of commercial education in European countries, especially in Germany. The extraordinary industrial development of Germany since 1870 was attributed by the Germans themselves and by competent observers in other countries to the system of trade and commercial schools which had been highly developed there. The experience of Germany had demonstrated beyond dispute that a system of industrial education can increase industrial efficiency. It had also demonstrated that there is a body of business facts and principles that can be correlated and made the basis of scientific instruction. Second, the war with Spain had just awakened in the mind of Americans the conception that the United States has a part to play in world affairs, and that that part will take the form chiefly of the preservation of the open door in unexploited markets and of competition for a place in the commerce of those markets. Third, the industrial situation in the United States had become such as to convince many manufacturers of the necessity of finding markets abroad. The development of manufactures during the preceding decade had resulted in the creation of an industrial plant which, in order to produce at its maximum of efficiency, must have at times a larger consumption than that afforded by the domestic market. The increasing export of manufactures had been largely the result of the necessities created by this situation. It was realized that the development of an export trade would be 110 slight undertaking, for it would mean a competition with Germany, Belgium, and England, countries in which efficiency in production and efficiency in exploiting distant markets had been highly developed by technical education. To those business men in the United States who were inspired by the desire to develop an export trade, it seemed essential for the United States to neutralize the technical advantages possessed by her leading rivals, by the development of a not less efficient system of industrial education. Fourth, aside from any question of the development of an export trade, the industrial situation in the United States made it desirable to establish trade and commercial schools in the interest of both employer and employee. Within a quarter of a century had come about a radical change in the conditions of business success. On the one hand, manufacturers were no longer in command of isolated markets, for with the development of cheap transportation the United States had become a unified market. In the keen competition of this larger market, profits were narrow and business could be successful only with the application of the highest skill. The units of business had become larger, and these individual units as well as business in general had become more complicated. Management had come to mean the smooth running of a complex, nicely adjusted machine. The running of such a machine requires the highest degree of ability, in both principal and subsidiary positions. It is necessary for the business man to secure the most efficient management and labor in every department. On the other hand, this increasing complexity of business had made it more difficult for the young man, by the process of old-fashioned "experience," to become an efficient laborer, and especially to rise to positions of responsibility. The young man of the earlier generation had entered a business not highly complex, and grew with the business. The young man of the later generation had to enter a business already highly complex, in which the process of growing up with it was exceedingly difficult. The young man of the earlier generation could pass readily from department to department, while the young man of the later generation was compelled to take up at once the performance of highly specialized routine functions, a situation which retarded rather than promoted the development of breadth and depth of view. The situation had become such as to make it necessary that this breadth and depth of view which makes the successful manager, should be developed before the young man entered upon his routine work. Its development meant the establishment of a system of industrial education. Fifth, many businesses had come to require the application of highly developed sciences, a knowledge of which could be obtained only by the training offered by institutions of higher education. As examples of this one may mention the actuarial work of a life insurance office, and the work in the foreign exchange department of an international bank. Banks engaged in international banking in the United States have been compelled to send for men trained in European commercial schools in order to secure efficient managers of foreign exchange departments. Sixth, from the point of view of the relation of government to industry there was a growing opinion that it was desirable to relieve the scarcity of business talent, in order that society might have a body of expert opinion upon which it could rely in the solution of quasi-business problems such as the taxation and regulation of corporations. These influences brought about the recognition that it was desirable to develop in the United States as efficient a system of industrial education as was possessed by any other country.

Higher commercial education in the United States aims to accomplish practicable results. It does not presume to create the genius for business; it aims to enable genius to find and express itself. It does not consider it profitable to teach the petty routine of a business; it aims to enable students to perceive and comprehend the common principles underlying routines and systems. What it does aim to do is, on the one hand, to teach the technique of a business, and, on the other hand, to help the student towards that knowledge of the facts and principles of business which distinguishes the "long-headed business man." The first aim is to make him an efficient routine clerk; the second to enable him eventually to attain the more responsible positions. It does not presume to do away with the necessity for "experience," or to enable the student to avoid apprenticeship. It aims to make experience richer, and to make possible an abridgment of the period of apprenticeship, according to the law that one gets out of experience a knowledge proportional to the information one takes into it. Its schools aim, when they shall have become as highly perfected, to accomplish for the young man entering business, what schools of law and medicine aim to accomplish for young men entering those professions.

The forms of organization presented by the various schools of higher commercial education in the United States fall into two well defined classes. One class, to which all except the Tuck School belong, represents that form of organization in which the commercial courses are offered in the undergraduate curriculum. In some schools these courses are offered as early as the first year, in others not until the third year. It will be observed therefore, that the use of the word school in connection with these courses is incorrect; their relation to the curriculum is not that of a school, but corresponds rather to the relation of courses that lead to a particular degree. In some institutions these commercial courses lead to a special degree, that of Bachelor of Commercial Science, but in most cases they lead to one of the conventional bachelor's degrees.

Up to the present time the Tuck School has stood alone among commercial schools as representative of the second of the classes into which the forms of organization fall. As has been suggested, the "Dartmouth idea" represents, in its first aspect, the theory that the college, while modern in the methods of its instruction, in the wide range of subjects taught, and in the system of allowing the student a great freedom in the choice of subjects, should preserve the essential feature of the older college, namely, the aim to discipline and broaden the mind and to promote culture. In accordance with this idea, courses in the undergraduate curriculum should not be too specialized, should not, at any rate, aim to train for any particular field of activity. The college should, through the instrumentality of college association as well as of the classroom, aim to develop the man, and should leave to the special school the development of the specialist. The "Dartmouth idea" represents, in its second aspect, the theory that courses which aim to train the specialist should be offered in a separately organized school, not alone for the sake of preserving the college ideal, but in order that the courses intended to train the specialist may be made more efficient. The separate organization promotes in several ways the efficiency of the specialized courses. If the separate school is a graduate school, as is the Tuck School, the student comes to it with a maturer mind; a solid foundation for specialization has been laid in the college. With students of mature minds, the instructor can consider problems of a genuinely practical nature; such problems, for example, as are considered practical by the program makers of bankers' conventions. When offered in the undergraduate curriculum, to students of relatively immature minds, these practical courses tend to degenerate into practice courses. The purpose of the student in the separately organized school is more serious, and the requirements of the school may be more severe. Having left the college, where "rubbing against men" is not less important than contact with instructors, where athletics, debating, and College Hall have a place with Livy and Euclid, the student, realizing that now he is training himself for a struggle, will put all his energy into his work, and will sanction the school's demand for all his time and all his mind. The attitude towards his work of the student of the law, medical or engineering school is in marked contrast to the attitude of the same student towards his work when in college. The separately organized school, like the German commercial school, looks upon business as a profession, and makes possible the development of a professional esprit among its students. Such an esprit in itself makes the student's work more efficient.

In one respect only does the undergraduate form of organization possess an advantage over the form of organization represented by the Tuck School; it reaches a greater number of students. The very fact, however, that the graduate organization does not reach so large a body of students is a proof that it operates as a selective force, eliminating those whose enthusiasm for the calling does not stand the test of a year of hard, special preparation. One of the problems which has arisen in connection with undergraduate commercial courses is the relatively inferior work of the student, due in part to a lack of serious purpose. There is such a thing as cultivating intensively as well as extensively, and the intensive cultivation of a small area is as great a social service as the extensive cultivation of a larger area.

A brief examination of the courses required for entrance to the School, and of the work offered, will indicate in what way the "Dartmouth idea" has been carried out in its organization. The Tuck School offers a course extending through two years, the first of which is identical with the College Senior year, the second of which is graduate. It requires, therefore, for admission three years of college work. The School prescribes certain courses which must be included in this three years of preparatory work. It must include the elementary courses in English and in at least two modern languages, the elementary courses in history, political science and sociology, and elementary and advanced courses in economics. The work of Senior year of the College, that is, of First Year of the Tuck School, presents two elements. The first element, consisting of advanced courses in economics, is intended to complete the theoretical foundation for the specialized, practical work of Second Year; the second element, consisting of certain general, basic commercial courses - like commercial law and commercial French, German or Spanish—is intended to effect the transition to the work of Second Year. This First Year of the School is really a transition year; it is not considered by the School as representative of its commercial work. It does not offer the opportunity for specialization for a particular business, and is not, considered in its entirety, a specialized course. It is accepted by the College as the final year's work for the bachelor's degree.

In certain instances some specialization is possible. If a student, for example, has made up his mind to specialize in insurance in the Second Year, he is permitted to specialize in mathematics in First Year; if he intends to train for such a business as aniline dye manufacture, he is permitted to specialize in chemistry in First Year. This specialization in the First Year, it should be observed, is not a specialization in commercial courses; it is a specialization in academic courses as a foundation for commercial work. It is not the sort of specialization one finds in the work of the Second Year.

It is in Second Year that are to be found the distinguishing features of the Tuck School. The work of that year presents the following characteristics. In the first place, the method is that of a graduate school, The instructor assumes a disciplined mind, that knowledge of general facts and principles which is imparted by four years of college work, a thorough training in economics, and a seriousness of purpose on the part of the student. Assuming a knowledge of the fundamental principles and of the more general facts of business, the instructor guides the student through an independent investigation of the complex facts and the advanced problems of business. In the second place, the courses offered make it possible for the student to specialize for that business in which he intends to engage. He may prepare himself for a particular manufacturing business, for foreign commerce, for railroad work, for insurance, for banking, or for any other special business activity. If, for instance, he intends to take up a banking career, he devotes all his time during the year to the study of corporation finance, the methods of bank organization and administration, the money market, the technique of domestic and foreign exchange, bank and investment accounting, banking law, and so on. In the third place, the work of this year is intensely practical;-practical in the sense that it examines the methods used in that business in which he is interested, and considers the relative values of different methods, and in the sense that it encourages him to form judgments on situations arising in the particular business. If, for illustration, the student is specializing in foreign commerce, he studies the actual documents employed, and investigates the meaning of every word and phrase in them. In corporation finance he is compelled to investigate the reports of a corporation over a series of years for the purpose of determining its financial policy and for the purpose of forming a judgment of his own as to its depreciation, reserve, and dividend policy. In his course in business management he investigates the actual methods for securing efficiency employed by typical firms, in every detail of the business, from the purchase of supplies to the sale of products. The Tuck School does not confuse practical courses with practice courses. Paper money and the grilled cashier's compartment are discarded as instruments unworthy the dignity of the student. There is no necessity of teaching the one thing the student is sure to get in his first few weeks of experience, namely, petty routine. Only in so far as the student makes entries in his work in accounting, or devises systems in his work ill business management, or plots curves to show the relation between the market rate and the discount rate, is there anything analogous to the practice courses of the business college and of some institutions of higher commercial education.

An important aspect of the practical nature of Second Year work is represented in the lectures by prominent business men. Through these lectures, or talks, the student is brought into contact with practical men and is given a view of the methods and spirit of the life for which he is preparing himself. While still in the school his adjustment to the actual conditions of that life is begun; his transition is less abrupt than that of the student who passes directly from college into business. Many college graduates fail in business because of their inability to make the sudden adjustment which is necessary. Under the influence of college life, the student's energy is frequently diverted from channels that make it immediately applicable to business purposes. One aim of the Tuck School is to direct this energy into proper channels.

It is sometimes asked whether the location of Dartmouth does not place the Tuck School at a disadvantage in comparison with commercial schools located in great commercial and manufacturing cities. It is the opinion of the Tuck School that the alleged disadvantages are not real. The institution in the large city may secure more lectures from business men, but the Tuck School is able to secure a satisfactory number. The value of lectures from practical men is not in direct proportion to the number of them. The best results are obtained from a proper proportioning of time between lectures by business men and class work. It is also the opinion of the Tuck School that the opportunities for observation afforded by location in a great city are greatly overestimated. With respect to that information which is acquired by casual observation, the student of the city institution does not seem to be better informed than the Dartmouth student. He may have a more intimate acquaintance with the superficial features of the city, but he knows little, if any more about the important facts of its commerce and manufactures. He does have the opportunity to visit, under competent guidance, manufacturing plants and stock exchanges, but, unless an unreasonable amount of time is spent in this way, such information as he acquires is superficial, and it is doubtful whether the time consumed finds a compensation in the result. Even if there is a slight advantage, made possible by these opportunities, for the student of the city institution, in another respect Dartmouth possesses an advantage that is just as important even from the point of view of training for business. Dartmouth's location, by its very want of "attractions," makes it impossible for the student to spend his energy in unwholesome, distracting interests; it compels the student to divide his time between the interests of study and the interests of a democratic student association. This association gives him an insight into human nature,—an insight which becomes an important asset in business life.

With regard to plant and equipment, the Tuck School is especially fortunate, as the result of an additional gift of one hundred thousand dollars from Mr. Tuck. Its building, an illustration of which accompanies this article, is a large solid structure of pleasing architectural features, and constructed to satisfy the especial wants of the School. On all three floors of the building are offices, and recitation and seminar rooms. On the first floor is a large lecture room equipped with a stereopticon and reflectoscope; on the second floor, a library and an accounting room; and on the third floor, a large room for the commercial museum, a work room for preparing exhibits and for mounting maps, and a dark room for making lantern slides for purposes of instruction. In a recitation room on the third floor is a stereopticon and reflectoscope for small classes. In the accounting room is a Thatcher slide rule and a comptometer for insurance and other calculations. The library contains some ten thousand books and pamphlets relating to commerce and industry, contains files of the leading commercial, financial and trade periodicals, and receives the current numbers of some seventy-five of these publications. Among the contents of the library are bound sets, some complete and all nearly so, of the LondonEconomist, the Statist, L’Economiste Francais, the Commercial andFinancial Chronical, the Journal ofthe Institute of Bankers, the LondonBankers' Magazine, the New YorkBankers' Magazine, Bradstreef’s, the Journal of the Canadian Bankers'Association, the Journal of the Institute of Actuaries, the Transactionsof the Actuarial Society of America, the Railway Age, and the RailroadGazette. It contains also less complete sets of the consular reports and of other official industrial publications of the leading countries. It is the intention to build up the commercial museum so that it shall contain exhibits of all important industries of the United States, the exhibit of each industry to be complete in itself, and to contain articles representing all aspects of the industry, from photographs and plans of the plant, through raw material, partly manufactured and manufactured products, to the methods of packing and advertising peculiar to the industry. The museum is intended to be a place for the student, not merely a place for the curious.

Is the Tuck School accomplishing its purpose? So far as the short period of its existence permits one to judge, this question may be answered affirmatively. From the point of view of its obligations [to the College, it has called in specialist instructors, a part of whose time is given to undergraduate work in the College. It has, beyond question, been one of the influences behind the marked increase in attendance, for students have been attracted to the College in order to work up to the Tuck School. It has also had that wholesome influence on undergraduate work which always results from the presence of graduate work. From the point of view of its obligations to the individual student, it has offered the opportunity to train for business, a life work into which so many Dartmouth students are entering. That body of students who have taken advantage of its opportunities is making the same high record in the field of business that has been made by the graduates of the Thayer School in the field of engineering. The careers of Tuck graduates, of which a careful record is kept, show a higher rate of advancement, measured in wages received and in responsibility of positions, than is shown by any published record of a similar kind. From the point of view of the business community, the School seems to be fulfilling its purpose with the same efficiency. The rate of advancement of its graduates is an indication of the valuation of their services by employers. A more significant indication is the fact that the School, without effort on its part, could place each year more men than it graduates, and a still more significant indication is the fact that requests for men have been received by the School, which have taken the form of requests for "another man like Mr._," an earlier graduate. In view of these evidences of the fulfillment of its purpose, and in view of an increasing appreciation each year on the part of undergraduate students and of business men, of the thoroughly practical and efficient work of the School, there is every reason to feel confident that it is justified in looking forward to a career of usefulness, and of credit to Dartmouth College.

LIBRARY

LECTURE ROOM

ACCOUNTING ROOM

COMMERCIAL MUSEUM BEFORE INSTALLATION OF EXHIBITS

Professor Harlow S. Person, Secretary of the School

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE FOOTBALL RULES OF THE NEXT SEASON

April 1906 By E. K. Hal '92 -

Article

ArticleAT a meeting of the Faculty early in the year the following vote

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleFIRST TRICOLLEGIATE LEAGUE DEBATE

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE SUPPLEMENT TO THE GENERAL CATALOGUE, AND SOME OF ITS FACTS

April 1906 By Charles F. Emerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1887

April 1906 By Emerson Rice -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1894

April 1906 By Charles C. Merrill

Article

-

Article

ArticleMorrison Joins Faculty

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Article

ArticleD.O.C. of Boston

May 1933 -

Article

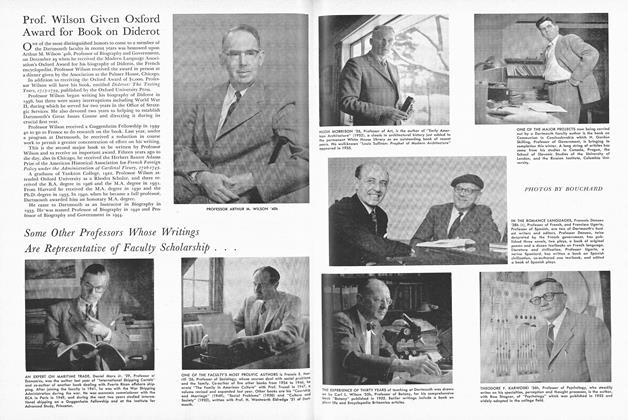

ArticleSome Other Professors Whose Writings Are Representative of Faculty Scholarship...

February 1954 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Gets off to Strong Start

May 1955 -

Article

ArticleCrossing the Green

APRIL 1986 -

Article

ArticlePress

June 1955 By ARTHUR DALEY