THE proposition which was presented this year to the American Intercollegiate Football Rules Committee was in its statement a very simple one, namely, "The game should be made more open, mass play should be abolished, unfair and unnecessarily rough play should be eliminated, and provision should be made to insure a more uniform and stringent enforcement of the rules." The working out of the proposition, however, has been much more difficult.

It seemed to be quite generally agreed by both the friends and critics of the game that changes must be made, but there was very little unanimity of opinion as to the manner in which the desired results might best be worked out.

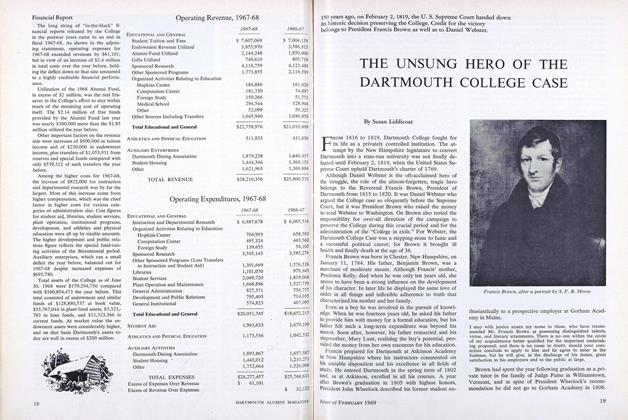

I have been asked to write for the benefit of the readers of THE DARTMOUTH BI-MONTHLY an article explaining the changes in the rules by which the Rules Committee has undertaken to solve the problem.

The work of the Committee divided itself into two parts,--one dealing with the ethics, and the other with the technique of the game.

The technical side of the question presented the problem of the working out of changes in the rules which would tend to strengthen, the offense and weaken the defense, it being universally admitted that with the present style of defense it would be impossible to develop to any great extent an open or end running game.

The Committee undertook to accomplish the solution of this problem by a combination of somewhat radical changes-increasing the distance to be gained in three downs from five to ten yards, putting a price of five yards on a tackle below the knee, making everyone on side when a kicked ball touches the ground, the introduction of the forward pass, and requiring the five centre men of the side in possession of the ball (with one slight exception) to be on the scrimmage line when the ball is put in play.

In order to fully understand the basis for the belief of the Committee that these changes will tend to bring about the opening of the game and to a large extent the abolishment of mass play, these changes should be considered in connection with their bearing upon each other rather than separately.

The increasing of the distance to be gained in order to retain possession of the ball seemed to be of fundamental importance, for so long as it was necessary to gain only five yards in three downs, or an average of a little less than two yards on each play, the attack was almost certain to be directed at the centre. This had been the trouble in the past. No captain would take the risk of much end play when he was reasonably sure of making his distance by pounding the centre, thus retaining possession of the ball. This tended toward an extreme development of concentrated and mass play, resulting in short consistent gains and a less interesting game. Judging from the experience of the past it is not probable that between evenly matched teams either team will be likely to be able to gain the new distance with this style of play.

The Committee has endeavored to still further decrease the possibility of gaining this distance by consecutive centre or mass plays by eliminating some of the weight which has heretofore been available for piercing or smashing the line. This has been done by the rule providing that the side in possession of the ball shall have at least six men on the line of scrimmage, when the ball is put in play, five of whom shall be the five centre men. This eliminates the guard back and tackle back plays, and means that the only men who can be used for line bucking are the backs and ends. If, as seems almost certain in the game which will be played under the new rules, open play and end running will predominate, it is believed that no captain will feel justified in weakening his backs and ends, who under the new style of play must necessarily be faster and more agile than ever before, by tiring them out in any continued attack on the centre. Both centre and mass play will of course continue to be used occasionally—probably quite generally on the third down when there is but a short distance to gain, but in theory the new rules offer fewer obstacles and more inducements to the open game. It will be noticed that the same number of men and therefore the same formations may be used behind the line as heretofore. In other words, aside from the question of weight, this rule places no limitations upon the strategic possibilities of the attack.

The distance to gain having been increased to ten yards, and the attack having been weakened by the elimination of much of the weight which has heretofore been available, it of course becomes necessary to weaken the defense in order to give the lighter men who will now take part in the attack, or rather who are now available for the attack, an opportunity to gain the increased distance.

The Committee has undertaken to accomplish this by the forward pass, the tackle above the knee, and putting everyone on side on a kick as soon as the ball touches, the ground. The weakening of the defense for a long time appeared to be an almost unsolvable problem. There seemed to be no practical way to weaken either the line, or the secondary defense, the strength of which has been the feature of the development of the game during the past five years. Among various others, many suggestions came to the Committee proposing that the secondary defense be moved back and stationed at arbitrary distances behind the line—-five, ten, even twenty yards. This method of weakening the defense, however, seemed to be entirely impracticable, affording, as it would, endless opportunities for slowing up the game, and raising all kinds of complications. It seemed to be agreed, however, that if the secondary defense, or part of it, could be automatically stationed at some substantial distance back of the scrimmage line the problem would be solved'. It was finally decided that this might be brought about by putting everyone on side when a kicked ball touched the ground. This makes it unsafe to leave the back field protected by only one man, as has been the case heretofore; for instance, if a quarter back should see only one man of the opposing team in the back field he could signal for a low short kick, well to one side of the field, and his ends being on side as soon as the ball touched the ground, would stand probably much better than an even chance of recovering the ball, thus gaining the distance kicked. This danger it would seem ought to result in keeping at least two men in the back field, which must substantially weaken the secondary defense and afford a much better opportunity for running the ends.

The forward pass, it is believed, will also tend to weaken the defense materially by preventing at least part of the team on the defense from going into the attack (and thus putting themselves out of the play) too early in the play. A successful forward pass may entirely change the point of attack almost instantly, and the attacking side knowing where the forward pass is to go will have an opportunity to concentrate their interference to assist the man who is to receive the ball. If part of the defending side have put themselves out of the play by going into the first attack, the defense has been divided and the opportunity for securing good distance substantially increased. The kaleidoscopic possibilities of the forward pass will probably have the tendency to keep part of the defense out of the play during the first second or two after the ball is put in play, and thus tend to give the play a much better opportunity to get under way.

Those who played the game in the latter part of the '80s and the early '90s will recall the clever running in the open which used to be done by some of the best backs, and how the runner who had succeeded' in getting into a broken field would then protect himself from all attempts at a tackle by using either the straight arm or what was known as the "cut-off" - the free arm swing used in cutting down on the arms of the man attempting to make the tackle. This style of defense by the man carrying the ball has almost entirely disappeared, and it is the hope of the Committee that it will be restored by the provision which puts a price of five yards distance on any tackle below the knee. With an unrestricted low tackle permissible the runner does not have a fair chance, for he has no way of protecting himself against a tackle which is aimed below his knee. For this reason, the low tackle has been restricted. It is to be considered, not a foul, but a perfectly legitimate tackle which may be used at any time when a man wishes to give up five yards distance for the privilege. In this connection hurdling has been abolished, sothat what was intended as a high tackle cannot be converted into a tackle below the knee by the runner's attempting to hurdle the tackier. Tackling below the knee is still permissible in the line of scrimmage without penalty.

The foregoing constitute the principal changes tending to affect the style of play in next season's game. Many minor changes have been adopted, some necessarily incident to the more fundamental changes already outlined—for instance, the man catching a kick is to be protected. If he signals for protection by raising his hand, he is entitled to immunity from interference, and having caught the ball may put it in play not only by a free kick as heretofore, but by a scrimmage if he so prefers.

The committee has attempted by other minor changes to clarify some things in the rules which heretofore have given rise to more or less misunderstanding and different interpretations. For instance "holding and unlawful obstruction” and the use of the arms in blocking off an opponent have been specifically defined, and the proper interpretation of the definitions will be illustrated by photographs in the rule book. The moment when the ball is to become dead has been defined more definitely with the expectation that it will result in preventing much of the "piling up" on the runner.

To sum up the technical changes in the rules, it is the hope of the Committee that the result will be a decided change in style of play. It is believed that the premium has been removed from beef—and transferred to agility, speed, cleverness and strategy. Theoretically, at least, mass play and concentration will no longer predominate, and the rules for next year promise a running game, with plenty of kicking and fast work in the open.

The ethical side of the problem, which is the most important as well as the most difficult to handle, simply presents the evil which threatens, in various degrees, all kinds of amateur sports, namely, the tendency of players to sacrifice the true spirit of amateurism—sport for sport's sake—in the attempt to win regardless of the means employed. It seems to be the American tendency to place more thought upon the end than the means by which the end is obtained. This is bad enough in business, but it is far worse in sport, and until our intercollegiate contests can be freed from the too prevalent opinion that it is the score which counts rather than the means by which the score is secured, college athletics will never be all that they should be—the standard for all amateur sport.

Unfortunately, the game of football as it has been played in the past offers more opportunities for unfair and unsportsmanlike play than any other form of sport. The number of men employed in each play, the close formation, the personal contact of the players, the ever changing scene of activity, the number and complication of the rules necessary to keep the game a scientific one, have all tended to give exceptional opportunity for infraction of rules and unsportsman-like play.

In the mere matter of making rules there seemed to be little which the rules committee could do to rectify this evil. No criminal was ever made an honest man by legislation nor does the Rules Committee undertake by legislation to convert a mucker into a sportsman. The Committee has undertaken, however, to decrease the opportunity for unfair play by opening up the game, and also to remove any incentive for unsportsmanlike conduct by making it too costly. This has been done by providing that men detected in misconduct shall be disqualified. Heretofore many of the unsportsmanlike offenses have been penalized only by distance. The Rules Committee has taken the position that it would not stand for "distance for dirt," and hereafter any man guilty of dirty play, will, if the officials do their duty, be promptly disqualified and removed from the game. The Committee has gone one step further and recommended that if any man is disqualified a second time, during the season, the institution which he is representing shall debar him from play in all games for the rest of the season. In other words, the Committee has done everything in its power to keep the muckerish player on the side lines, where he will have no opportunity to continue to leave his blighting mark on the game.

The Committee, however, has taken still another step in endeavoring to rid the game of the muckerish player by appointing a sub-committee who are to consider ways and means to bring about a strict, courageous, and impartial enforcement of the rules by officials. This it hopes to do in two ways: First, by attempting to impress upon all men who act as officials in football games next fall that they are there representing not the captains or the coaches of the teams by whom they are employed, but representing the game of football, the greatest of intercollegiate sports; and that in behalf of its good name they are to enforce its rules—regardless of the consequences in the particular contest of which they are judges; second, by endeavoring to secure the cooperation of the football-loving public in the creation of a sentiment which shall absolutely refuse to stand for winking at or excusing infractions of the rules. If the rules are not right they will undoubtedly be changed another year, but so long as the rules exist they stand as the established rules of the game, and no team which allows them to be disregarded should receive the support or approval of its college or the public. It is the belief of the Rules Committee that if the public will take this view of the question, and stand back of courageous officials who enforce the rules regardless of whether it loses or wins games, most of the unfriendly criticism of football will disappear within the next year.

It is a royal game, far too good a game to lose, but it is absolutely certain that it cannot stay unless it is played in the proper spirit. To insure this,players, officials, college men, and the public must all cooperate to demand and insist that the game be played fairly, and that to this end the rules be enforced without fear or favor, strictly, promptly, and regardless of consequences.

In the past the game has been abused—in part thoughtlessly, and in part intentionally. The abuses must be eliminated. It is not to the enemies of the game but to its friends that the game appeals for this protection. Upon them devolves the duty to see to it that the game is played in a manly way—in the spirit that characterizes the thoroughbred sportsman. It is said that the game of football has reached a crisis, and that it will be on trial for its life next fall. It may be true that a crisis has been reached, but it is not the game that will be on trial next fall, it is the friends of the game—and once they realize' their responsibility they will eliminate from the game the features which have threatened its existence. The game of football has too much inherent virility to be successfully attacked by its enemies. It is too rich in tradition and too noble a sport to be allowed to perish through the negligence of its friends.

E. K. Hall '92, of the American Intercollegiate Football Rules Committee

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL

April 1906 By Harlow S. -

Article

ArticleAT a meeting of the Faculty early in the year the following vote

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleFIRST TRICOLLEGIATE LEAGUE DEBATE

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE SUPPLEMENT TO THE GENERAL CATALOGUE, AND SOME OF ITS FACTS

April 1906 By Charles F. Emerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1887

April 1906 By Emerson Rice -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1894

April 1906 By Charles C. Merrill