When Stuart V. "Mike" Smith '57 was a Dartmouth undergraduate, the Connecticut was an abused and polluted river.

Two years after Smith graduated, in 1959, Dr. Joseph Davidson, then the president of the Connecticut River Watershed Council, and his wife Madeline, traveled from the source of the river on the Quebec border to where it empties into Long Island Sound at Old Saybrook, Conn. They had to don gas masks at times to filter out the stench of the raw sewage that spilled into the river from many towns along its 410-mile course. In addition, pulp mill liquors and paper mill dyes contaminated the river in its northern reaches, and industrial offal fouled the river where it passed through the mill towns below.

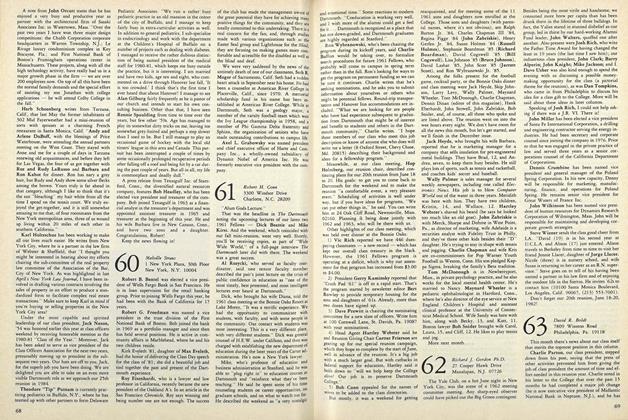

Early this summer, Smith and other members and friends of the Watershed Council recreated the original source-to-the-sea expedition, but went Dr. Davidson one better by canoeing the entire length of the river. Davidson had traveled by motorboat, plane, car, and canoe.

Smith, a resident of Lyme, N.H., and the president of Dartmouth Printing in Hanover, was one of two people to make the entire 23-day trip. He is a C.R.W.C. board member.

Six voyageurs, including Mike's daughter Jen- nifer, C.R.W.C. Associate Executive Director Bob Linck, and Executive Director Terry Blunt, began the trip on Mt. Prospect, where the Connecticut River is less than two feet wide as it spills from the outlet of tiny Fourth Connecticut Lake.

Other C.R.W.C. members drifted in and out of the expedition according to the demands of shoreside life.

The trip was undertaken both as a fundraiser to support C.R.W.C. programs and to dramatize 'he progress that has been made in cleaning up the Connecticut.

The canoeists found the river pristine in its upper reaches, except where clearcutting had scarred the land along its banks, causing the thin soil to erode with every rain.

Up north, the Connecticut is not the tame river that flows past Hanover. Between the Se- cond and First Connecticut lakes, the river drops more than 100 feet per mile, creating ten- and 20-foot waterfalls and rocky rapids too dangerous to run. Smith and the rest of the group lined the canoes through this stretch, then portaged across the logging slash from a clearcut to avoid a series of falls. In addition, the rains of early June had created mile after mile of Whitewater that challenged the canoeists and broke the monotony of paddling on the lakes that the many hydroelectric dams have made of the river.

The group tested water quality along the way and found that in most places the Connecticut was clean enough to support trout and the salmon that are making their way upriver over the newly-installed fish ladders at Vernon.

With more than 100 sewage treatment plants having been installed in the valley and regulations governing industrial effluents having been tightened, the Connecticut is coming back to life. Seventy per cent of the river now carries a class "B" swimmable rating. Dissolved oxygen levels throughout the river were between seven and nine p.p.m. suitable for trout.

More cleanup work remains to be done, however. In places, raw sewage still rides the rapids, and where the river passes through Bellows Falls, Holyoke, and Springfield, it is still badly polluted.

Twenty-three days after the group had set out, they arrived at Old Saybrook Light at the river's mouth. They had canoed the entire length of the Quinni-tuk-qut, the "Long Tidal River," dis- covered by Adrien Block in 1614 and paddled by Dartmouth drop-out John Ledyard in 1773. And they had found a river that may have been more like the one of Block's and Ledyard's day than Davidson did 22 years ago.

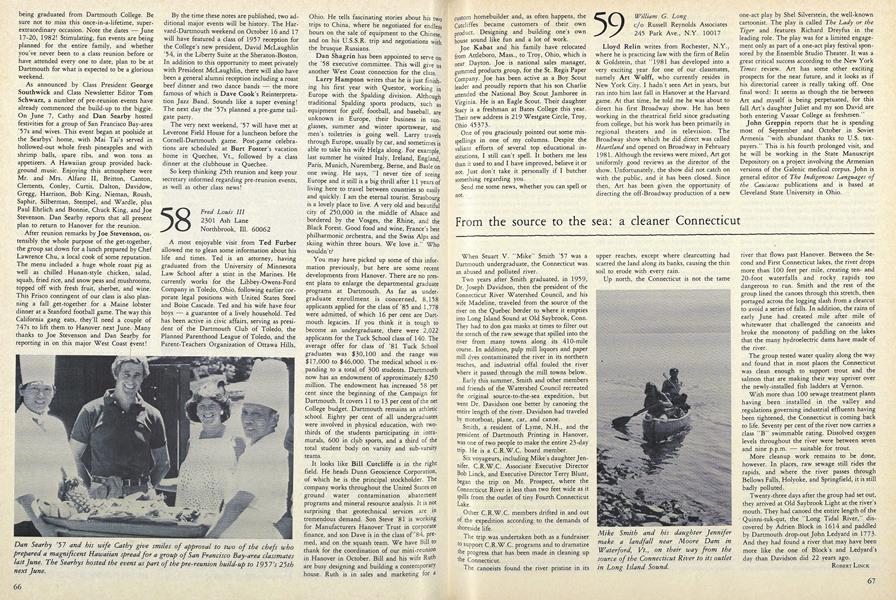

Mike Smith and his daughter Jennifermake a landfall near Moore Dam inWaterford, Vt., on their way from thesource of the Connecticut River to its outletin Long Island Sound.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

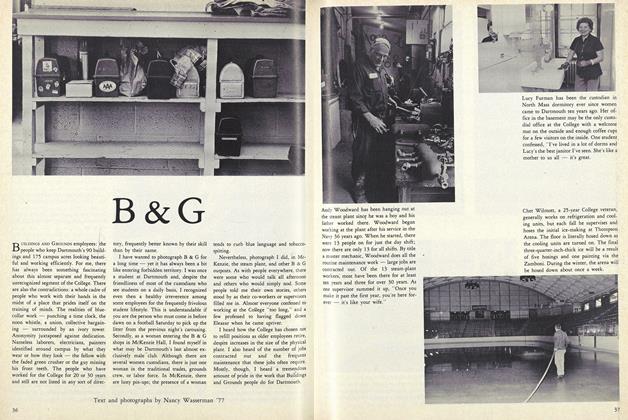

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn