In the Yale Courant of July 25, 1866, (Vol. I, No. 30) appeared the following plain sign of new and conscious adornment with brilliant hues:

" 'Show your colors.' At Worcester, day after tomorrow, every son of Yale and Harvard will be called on to show his colors. Yale is 'true blue,' Harvard is red. Last year Harvard was very profuse in this display up to the close of the race; Yale was lacking. Some wag remarked that Yale boys were ashamed to wear blue when every Harvard man wore it on his phiz. Though Harvard wears it, let every son and friend of Yale be proud to show their love and loyalty by wearing the blue. Hamilton College has just adopted orange as the college color. Williams has purple."

A Dartmouth boy, Alfred A. Thomas '67, now a lawyer in Dayton, Ohio, was one of the spectators at that regatta, two days later. He was to be one of the founders and early contributors of the Dartmouth, and in its second number (Feb., 1867) he published a delightful account of the brilliant scene and events at Worcester, over the signature of "Coila." It would be entertaining to quote the whole, but only two expressions bear upon the present inquiry. After a facetious description of a Harvard student the writer says:

"All" (clothes and manner) "say Harvard in plainer terms than the college color or lettered ribbon" ; and "on the foremost boat the red caps of Harvard."

In a recent letter, Mr. Thomas says: "At the Harvard-Yale boat race at Lake Quinsigamond in the summer of '66, I first saw college colors in use;and felt denuded because Dartmouth had none."

And Frederick G. Mather, also of '67, writes of Thomas:

"He was the originator, promoter, and executor of the idea. ... It was when he attended that regatta in the summer of 1866 that he noted that several of the colleges had selected their colors and that Dartmouth had none."

William A. Ketcham, of the same class, gives a different account of the source of the suggestion :

"As I recall it, Amherst had come up with flying colors in '66's senior year, to teach us how to play baseball,—and she did it to our sorrow. Every Amherst son sported, as I now recall it, mauve and white as their college colors, and we had none, and the absence of a color that we could claim as our own rankled within us. It looked as though we were not up to date*. Sixty-six did nothing about it, however, and it was not until '67 came to the front as the senior class that anything was done."

Evidently there were two sources of suggestion; Ketcham, a mighty man with the bat, received his suggestion from the Amherst team, while Thomas's came from the regatta which he had seen.

There is some uncertainty about the roles of the various participants in the action.

Thomas says: "When college session began in September, '66, the subject came under discussion; a meeting in college chapel, just after morning prayers, was held; I don't know who presided. There was no secretary. I was deputed to make the motion to adopt green as the college color, and to support the motion with brief explanation. This I did, and the motion was adopted. We had then no college publication. But the Dartmouth Magazine was begun in the January following, and in the February number the claim of Dartmouth to the color was published.

"Meanwhile we were apprehensive that Dartmouth's claim to the color would be jumped. Mather said he could bring about its publication in some college periodical; and he did so to hold our claim down."

Mather says: "I think Ketcham, of '67, was called to the chair. Thomas then mentioned the incidents, as noted above, at Worcester; showed the need of a college color for Dartmouth, and moved to adopt the color—green. This was carried without the suggestion of any other color. Indeed, it was the only decent color that had not been taken already."

And Ketcham's recollection is: "I do not recall who was president or chairman of the meeting. I feel quite sure that I was not,—I should say that I was chairman of the committee to whom the matter was referred, and made the fight for the color."

There is, however, little doubt about the time. "The action of Dartmouth was taken in September or October, 1866—" (Mather). "When college sessions began in September, 1866, the subject came under discussion—" 'Thomas). "I should say it was the latter part of September, or early in October—" (Ketcham). And we find that it was indeed brought to notice with no uncertain sound, in the HarvardAdvocate, Oct. 12, 1866, (Vol. II, No. 2):

"College Colors. Our correspondent at Dartmouth wishes us to notice that the Dartmouth students have adopted green as their color, their selection being Somewhat influenced by the fact that was necessary for their institution, 'as one of the original colleges of the country,' to be represented by one of the primary colors, and green was the only one left to them. He also suggests that any man who persists in 'cracking the feeble jokes so threadbare and hackneyed on this really beautiful color,' while our correspondent is 'a wearing of the green,' will be likely to have his 'head cracked' at that gentleman's expense. This had best not be forgotten.

"Perhaps it is worth while to mention what colleges have thus absorbed the primary colors. Harvard has always worn the various shades of red, one of which might well be assigned to each class. Yale wears blue. Brown is as sober in its aspirations as its name implies. Williams has taken purple, Hamilton orange, and Amherst, we believe, yellow.''

All agree that the adoption of the color was formal, in mass-meeting, immediately after morning prayers, in the Old Chapel. This style of massmeeting, often stormy and always uproarious, was in vogue many years later; unhindered and apparently unquestioned it abbreviated the morning recitation, or eliminated it altogether, thus bringing joy to the unprepared.

Mr. Ketcham adds some picturesque details of the discussion:

"If you will recall, this took place not very long after the Fenian excitement and the St. Albans Raid, and 'The Wearing of the Green,' except in Boston, was not especially popular, and I recall that objection was made that it would be thrown up to us that we were from the country, that we were Irish sympathizers, and all that. Personally I have always been fond of that color. The green hills of Vermont that our eyes looked out on every day and hour, were to me very attractive, and I insisted that if the College did not have standing enough to get away from the Fenian idea or the general impression of verdancy sometimes associated with the color, we were not fit to have a color at all. And in addition to this, as I recall it also, all the other primary colors had been selected, and it was either to take green or get some kind of a combination, and as the College was one of the older institutions. I think it was urged that to select a combination would be to put us in a class with the younger colleges. At any rate after a somewhat interesting fight green was selected, not with unanimity, but with enough of a majority to be entirely satisfactory all around. The color selected was just green, nothing else. There was no nile green, robin egg blue, invisible green, or any of the many shades of green with which my daughters are acquainted but I am not, but just simply plain green, and that is about all the information I can give you."

The Rev. Howard F. Hill, of '67, publishes in the Dartmouth, Jan. 28, 1898, an account of the selection of the Dartmouth color different in several points from the accounts cited. It is his recollection that in the early summer of 1866 Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Bowdoin, Williams had chosen colors (though it was Hamilton, and not Princeton as he thinks, that had chosen orange). About two weeks before Commencement temporary choice was made for Dartmouth of the color cherry, which he and others wore to the Worcester regatta that summer; but this was soon found to be too similar to Harvard's color, and in the fall the subject was reopened. "As chairman he presented the report and explained the choice (of green);" and in a letter to the writer declares that he is the "father of the green" and the correspondent referred to in the Harvard Advocate.

It looks as though the mother of the green might have been polyandrous. The time was ripe for suggestions from various sources, and it is not strange that the actors do not all remember alike; in the time and the final choice there is no conflict.

And we find in the second number of the Dartmouth—the number which con. tains Coila's account of the Worcester regatta:

"A connoisseur in delicate tints has favored us with the latest news respecting colors. The University of Michigan claims azure blue and maize as its distinctive badge. Nearly all the New England colleges have chosen their colors or combinations; many will doubtless follow the example set by the young Colossus of the West. Red, White and Blue yet remains for some patriotic institution to adopt; while lavender and yellow are at present disputed. We may add that Dartmouth claims green."

The question of the "green and white" — no longer a live one - was discussed in the Dartmouth by C. F. Mathewson, Dec. 10, 1897; by Mr. Hill Jan. 28, 1898; and editorially, Jan. 27, 1899. But if anyone has a lingering idea that green and white is Dartmouth's badge, let him consider in connection with the foregoing, that it is a discarded combination of Trinity's, and the present colors, according to Mr. Hill, of Bethany College, West Virginia, and of Illinois Wesleyan.

II

In the course of inquiries to establish the' exact time and occasion of the adoption of the Dartmouth color it became apparent that a wave of color-choosing swept through the colleges, at its height between 1865 and 1868, but with earlier start and later continuation. It was a little in advance of the present series of college magazines, as is shown in volume numbers of the Yale Courant,Harvard Advocate, and the Dartmouth already cited; and information in many cases must be sought from the memories of men rather than from the printed page. The scant and perhaps fragmentary information gathered here is no more than a starting point for chose who may be interested to follow to a conclusion the color selection of other institutions.

The earliest printed claim yet found is in the Williams Quarterly, August 1865:

"College Color—The want of some appropriate symbol by which the members of this college might be distinguished from those of other colleges, has at last been met by the choice of the Royal Purple as our college color. The college is indebted for the selection to the taste of some of the young ladies who have spent the summer with us."

Then follows the Yale Courant of July 25, 1866, cited above, which makes it plain that Harvard and Yale have colors so new that Yale's color at any rate needs to be brought to attention. The colors of Williams and Hamilton are the only others mentioned; and a recent note of inquiry to the librarian of Hamilton College brings the reply:- "there are no dates at hand concerning the question."

The Harvard Advocate, also cited, of Oct. 12, 1866, adds Dartmouth, Brown, and Amherst (with yellow).

From Brown, Professor Charles H. Hunkins (Dartmouth '95) writes, quoting Professor Wilfred H. Monro Brown '70:

"In 1868 Brown was playing baseball with Harvard and Yale. These two colleges had previously adopted magenta and blue for their college colors, Brown feeling the need of a color particularly at the time of these contests, the sophomore class, the largest and dominating class in college, decided to take action. Accordingly a committee was appointed by the class to consider the matter. Professor Monro was its chairman. The committee recommended Brown; it was adopted by the sophomore class in that year (1868) and 'then taken up by the whole college.' The color was first worn with 'Brown' stamped on the ribbon."

From the Advocate's allusion to Brown's color it appears that a color was in use and ascribed to Brown prior to the formal adoption detailed by Professor Monro.

Next in order is the note already quoted, in the Dartmouth of February, 1867, which adds only the additional item concerning the young Colossus of the West, and news of conflicting claims for yellow and lavender.

Later, there is a note in the YaleCourant, Vol. 11, No. 35, Mav 29, 1867:

"The students of Genesee College have adopted blue and orange as their color."

Prof. W. I. Fletcher writes from Amherst: "... the earliest information I can find here is the statement in Cutting's 'Student Life at Amherst' that the 'Students voted to adopt purple and white as College Colors, April 30, 1868.' Of course this is not inconsistent with those colors having been used, as your baseball enthusiast avers they were, by the ball team two years earlier.''

By this time great progress had been made and in April, 1868, the Dartmouth quotes from Qui Vive, the student publication of Shurtleff College, Upper Alton, Ill., first issued in January, 1868:

"College Colors—The list of colors now is as follows: Harvard, Red; Yale, Blue; Amherst, Purple and White; Brown, Brown; Dartmouth, Green; Bowdoin, White; "Hamilton, Orange; Williams, Purple; Union, Magenta; Michigan University, Azure Blue and Maize; Wesleyan, Lavender; Rochester, Magenta and White; Trinity, Green and White."

And Carmina Collegensia, Ditson, 1868, ed. by H. R. Waite, gives on page 251 a slightly modified list:

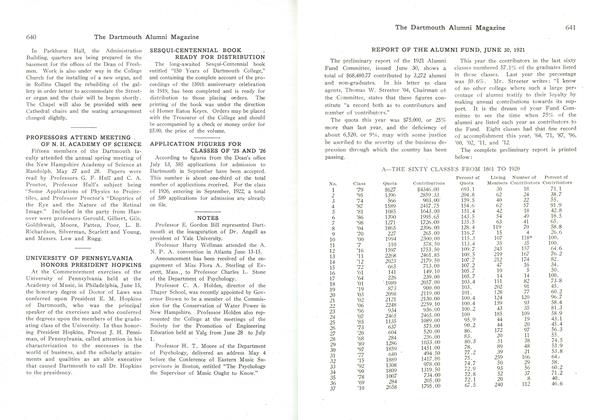

"College Colors—As a distinctive mark, fourteen of the foregoing colleges have chosen colors as follows:

"I Harvard, Red; 2 Yale, Blue; 3 Brown, Brown; 4 Dartmouth, Green; 5 Williams, Purple; 6 Bowdoin, White; 7 Union, Magenta; 8 Hamilton, Orange; 9 Amherst, Purple and White; 10 Wesleyan, Lavender; 11 Univ. of N. Y., Violet; 12 West. Reserve, Bismarck and Purple; 13 Michigan, Azure Blue and Maize; 14 Rochester, Magenta and White."

From 1868 until 1873 there is either quiet along the color line, or, more probably, a hiatus in our information; then follows the Renaissance of the Crimson at Harvard,and an inquiry into the origin and adoption of that institution's favorite pigment which seems to place it at the head of the procession.

The Harvard Magenta of Dec. 19, 1873,(Vol. II, No. 7), leads off with a beautiful specimen of speculative history :

"With whom the idea of a 'Collegiate Spectrum' first originated could hardly be ascertained now; but it seems the most natural thing in the world for a college, like other associations of men, to choose a color or colors to be the symbol of its individuality and of a friendly rivalry with other colleges. The custom has been undoubtedly borrowed from the English universities, and was probably adopted at once by all our prominent colleges, as soon as one of them had set the example. And is it not about time that it should be definitely settled what rays of the spectrum shall represent us? We do not know who selected our color, but we ought to know just what hue it is, which is to be our emblem. ... It is possible that we have had a representative color much longer than since 1859; and as the sanguinary magenta has come into existence since that date, it is reasonable that the former color was, what is now often attributed to us, crimson."

Notwithstanding this conclusion there is a note of perturbation when the Magenta again speaks, a little over a year later (Vol. IV, No. 10; Feb. 12, 1875):

"It becomes our painful duty to inform the H. U. B. C., the H. U. B. B. C„ the H. U. F. B. C„ etc., that the magenta which has graced so many victories, which was first displayed on Lake Winnipiseogee in 1859, and now adorns our Commons crockery, must be renounced. Union College has signified her willingness to enter the next regatta; Union College bears a Magenta standard; and Union College desires us to change our colors."

And two weeks of reflection do not improve matters, for on Feb. 26, 1875 (Vol. 5, No. 1), the Magenta adds:

"Again, Union claimed the color (magenta) in iB6O. Before what tribunal? Where was it widely displayed? The color was claimed only by being worn by some of the students of Union. ... The color of a college is determined when first worn in a race with other colleges."

The Harvard Advocate soon makes Harvard's claim definite, though without giving the source of its information (Apr. 16, 1875; Vol. XIX, No. 5):

"The color (Harvard's) came from the college boat crew in 1858. Before that no particular color was recognized in any American college as pertaining thereto. Boating men were the only collegians who had occasion to sport a uniform. .... Up to 1858 the crews usually wore straw hats, or sometimes caps, but in 1858 a handkerchief tied tightly around the head was used. ... The shade of red was very nearly a true crimson."

And on the 14th of May of the same year (Vol. 19, No. 7) the Advocate establishes the date of formal adoption from the records, which is evidently some years later than the actual use of the color:

"In the records of the H. U. B. C. for the year succeeding the Worcester Regatta of 1866, we find the following under date of Apr. 16, 1867: 'At this meeting there was also chosen a committee .... to confer with a committee from the H. U. B. B. C. and adopt a Harvard badge to be worn on all occasions when the college is concerned in either boating or baseball contests. The badge adopted by the representatives of these two clubs was intended to be common to both clubs and distinctive of our college. The color adopted was crimson."

And in the Harvard Crimson, the continuation of the Magenta, we find in June 16, 1876 (Vol. 7, No. 9,):

"A committee appointed to determine the shade of crimson reported in this issue of the Crimson. The report was adopted by the executive committee of H. U. B. C. and urged upon the college. "

The complement of this discussion is to be found in the records of a committee of Union men of which A. V. V. Raymond '75 (later, President Raymond) was chairman. It would seem that after comfortably talking it over by committee, Union established a claim to magenta that was courteously recognized, and Harvard gladly reverted to its original choice of red, or crimson.

NOTE: The writer gratefully acknowledges help in collecting material, from Mr. Eugene F. Clark 1901, Professors Wild of Williams and DeWitt Clinton of Union, as well as from those already mentioned.

E. J. Bartlett

Article

-

Article

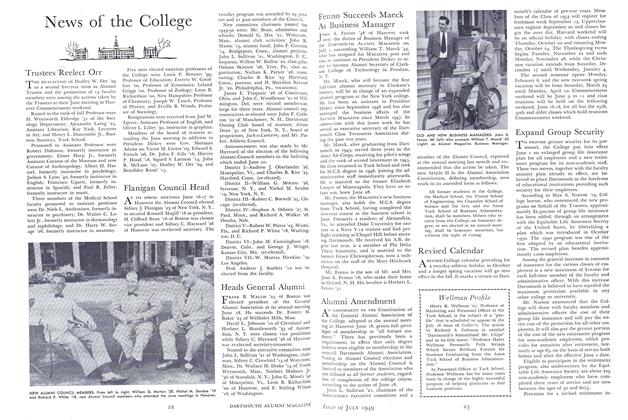

ArticlePROFESSORS ATTEND MEETING OF N. H. ACADEMY OF SCIENCE

August 1921 -

Article

ArticleWellman Profile

July 1949 -

Article

ArticleTHE HANOVER SCENE

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleBoys of Summer

MAY | JUNE 2014 -

Article

ArticleSOME CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDENT LIFE IN CAMBRIDGE

FEBRUARY, 1907 By G. F. -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

DECEMBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32