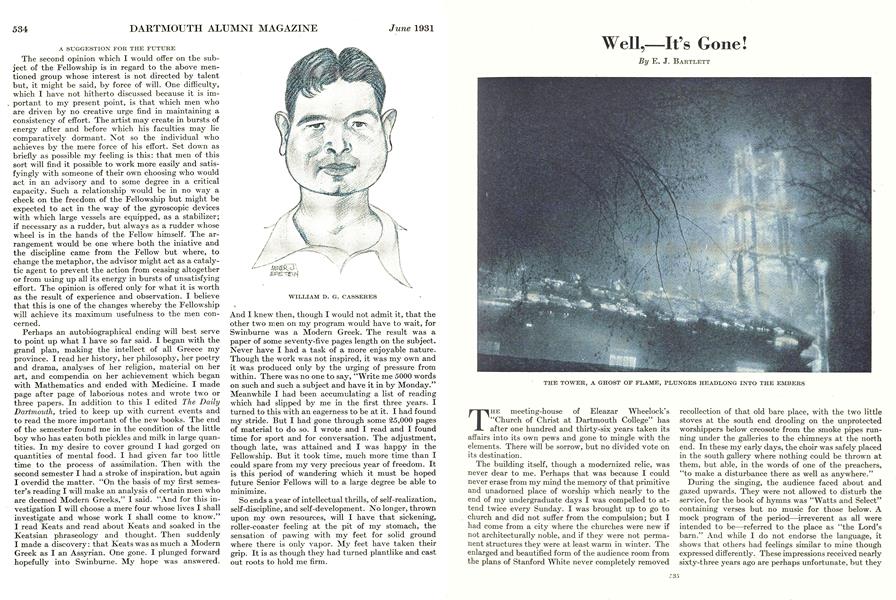

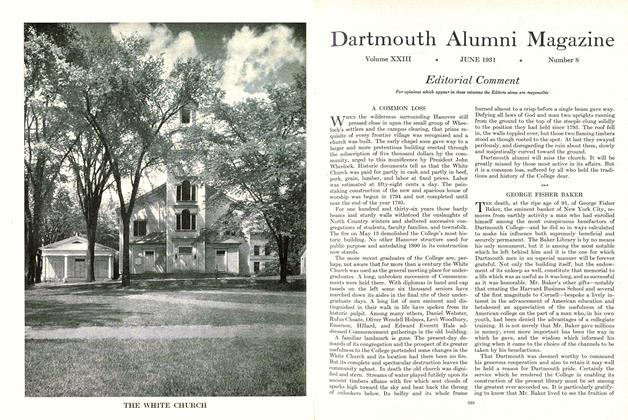

THE meeting-house of Eleazar Wheelock's "Church of Christ at Dartmouth College" has after one hundred and thirty-six years taken its affairs into its own pews and gone to mingle with the elements. There will be sorrow, but no divided vote on its destination.

The building itself, though a modernized relic, was never dear to me. Perhaps that was because I could never erase from my mind the memory of that primitive and unadorned place of worship which nearly to the end of my undergraduate days I was compelled to attend twice every Sunday. I was brought up to go to church and did not suffer from the compulsion; but I had come from a city where the churches were new if not architecturally noble, and if they were not permanent structures they were at least warm in winter. The enlarged and beautified form of the audience room from the plans of Stanford White never completely removed recollection of that old bare place, with the two little stoves at the south end drooling on the unprotected worshippers below creosote from the smoke pipes running under the galleries to the chimneys at the north end. In these my early days, the choir was safely placed in the south gallery where nothing could be thrown at them, but able, in the words of one of the preachers, "to make a disturbance there as well as anywhere."

During the singing, the audience faced about and gazed upwards. They were not allowed to disturb the service, for the book of hymns was "Watts and Select" containing verses but no music for those below. A mock program of the period—irreverent as all were intended to be—referred to the place as "the Lord's barn." And while I do not endorse the language, it shows that others had feelings similar to mine though expressed differently. These impressions received nearly sixty-three years ago are perhaps unfortunate, but they have value as experience. They carry me back into the 18th century and nothing can quite efface them. Of those in that meeting house at my earliest time four women are living, all residing in Hanover. Of the men who were there in 1868 I think there are only the few survivors of college classes.

ASSOCIATIONS AND TRADITION

But any feeling, or, more correctly, lack of feeling, I may have for the habitation is more than balanced by the memories and associations that cluster around it. They are many and varied. Far back in my college days, as an Exhibiting Junior I there told a waiting world how to manage some of its affairs. And through a freak of memory an incident recurs from Commencement, 1872. In those days bouquets, real bunches of garden flowers, were presented to young gentlemen by iadmiring friends. In my simplicity I thought of them as gifts from heaven like the rain, and no preparation was made for any token for me. A good kind lady, who has long ago gone to her reward, noticed the omission and hastened from the church to her garden and then back with a bunch of posies, which reached me only a little late.

When I came back to teach, in 1879, I no longer had to sit where misbehavior, if any, would be conspicuous, but soon had a pew on the center aisle. All about me were "the good gray heads whom all men knew," and Others. My father and mother were there almost to the end of their lives. And the very air is rich in the spirits "of just men made perfect." I can see in my mind's vision most of them now,—the doctors Frost, and Smith (who gave the communion table), when duty permitted them to be there, Professor Sanborn's massive head, Professor Noyes's silvery beard, the dignified and, as I thought then and do now, admirable Senator Patterson, Professor Proctor, learned and shy (we thought), the keen-brained and keen-eyed Charlie Young, before and after his years at Princeton, N. S. Huntington, our village banker and statesman, Charles P. Chase, who never missed a chance of helping a worthy student, good Dr. Peaslee at times, Frederic Chase and J. K. Lord (in the gallery) who wrote the large history of the College, Wells affectionately called "Stub," Dr. Leeds in the pulpit. I cannot name them all; nor do I follow any special order.

Many mothers will share the feelings expressed in a letter which has recently come to my house,—"I really was terribly upset, for that old church brought up so many memories. I can see my little children on the platform and in the seats at the Christ festivals and all the old friends sitting in their pews."

Of regular ministers I think there have been eight in my time, and countless "supplies."

It soon appeared that I was to take over the duty of receiving and disbursing the funds of the church, that is to be treasurer; and I served for several years. Then I was drafted into the Sunday School. It became a pleasant job, because Mr. Chase was superintendent, and I had a class of bright school girls. I fear it would not be polite to guess their average age now. Then, or about then, or some other time, it seemed that I (from lack of a competent person) must organize a summer choir. Thanks to the components of this choir—summer visitors and a few college men—it was a joy for several years. I wish I could again hear them sing "Hark, hark my soul" as arranged by Shelley. Later I had a class of college students in the church school; and, as perhaps the last of my services to the organization, I presided a few times at its business meetings.

For many years the church was the only audience room of adequate size in the village, and the number and variety of entertainments was considerable, mostly lectures and concerts. The Dartmouth Choral Society had its rehearsals in the vestry and its concerts in the church. Miss Sarah Smith was the leading soprano and in the earlier days long took charge of the church choir. I should like to be able to give a list of speakers of distinction to whom we had the opportunity to listen. I recall at once Matthew Arnold, Walt Whitman, Edward Everett Hale, D. L. Moody, Dr. Grenfel. Speakers from away were more distinguished but less numerous than now.

LINK WITH THE PAST

If from the time I entered college, nearly sixty-three years ago, I had gone back, another sixty-three years I do not think it would have mattered much to me if the building was only ten years old, or that John Wheelock was still president, or that Daniel Webster was but four years out of college. So I am aware that the period from which I start my knowledge of the building, three years after the close of the Civil War, may not deeply interest the college man of today. Still the experiences during nearly twice the average three score years and ten stimulate the imagination.

IMPROVING THE THEME

And its passing calls for reflection. Can it mean that the great educational institution needs no longer the inspiration of religion, and that science takes its place? Neither science nor religion have taken permanent form. But so far, science has made poor work of the application of the Golden Rule. Religion has moved towards it with painful slowness, but we can say with Galileo, as we look back only a few years, "It does move." Perhaps we shall find a way to do to others as we would have them do to us even in our business, national and private. But science has done an amazing work in making incredible things possible. How can we say "Contrary to the laws of Nature"? We can photograph a bullet or a fracture through all the surrounding tissue. We can listen to a speech in London or music in New York without visible connection. If a scientist can believe it possible that in the course of time a speck of inorganic matter can work itself into an assimilating reproducing mass of the most complicated chemical structure in nature, why may I not believe in the Resurrection? When astronomers tell us, and we believe them, that light from certain nebulae has been traveling 140 millions of years to reach us, why may I not believe in immortality? When we receive on good authority from the great telescope information of the incomprehensible speed, size and number of bodies within our heavens, must we discredit the simple words "In my Father's house are many mansions"? If Professor Jeans says that the Mind that presides over the universe is undoubtedly that of a mathematician, might not it be the mind of a father also? When physical philosophers reason that the universe is limited and that time might flow backwards does it remain much of an argument that a statement beyond our understanding is therefore untrue?

Churchly thoughts may travel far.

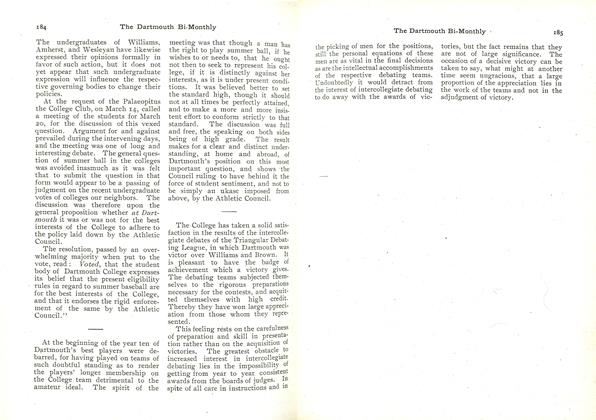

THE TOWER, A GHOST OF FLAME, PLUNGES HEADLONG INTO THE EMBERS

BAKER CAUGHT THE GLOW

QUICKLY RESOLVED TO BLACKENED BEAMS

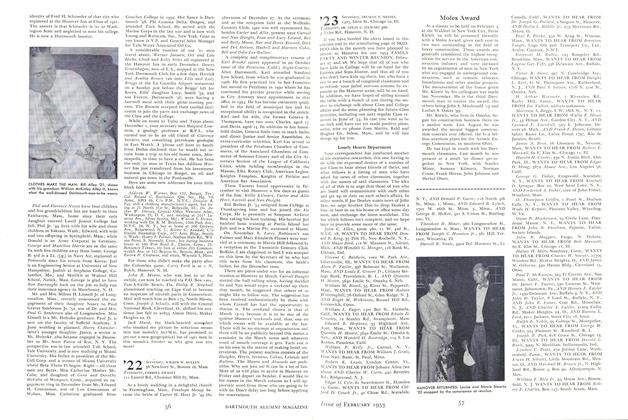

BEFORE'THE'REMODELING OF 1877

EARLIEST PHOTOGRAPH BY BLY (ABOUT 1869)

AFTER THE REMODELING BY STANFORD WHITE (1889)

DISSOLVED INTO ETERNITY

BOBBY HIMSELF

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleA Senior Fellow's Journey

June 1931 By John Butlin Martin, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Article

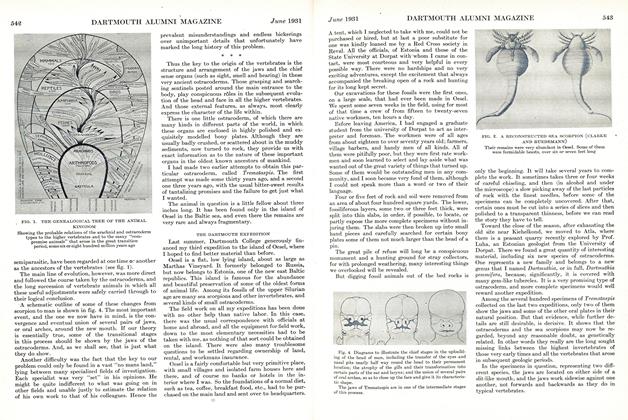

ArticleThe Dartmouth Expedition to the Island of Oesel

June 1931 By Wm. Patten -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931