The annual undergraduate upheaval known as "chinning day" passed into history early in December. As a result the bosoms of some fifty per cent of the freshman class have expanded an inch or so for the better display of cabalistic jewelry, while the fingers of the same number have begun to adapt themselves to the serpentine convolutions of mystic hand clasps. It is difficult to avoid wondering a little about the other fifty per.cent. What are the qualities that make some men the palpitating centers of frenzied chinners, while the other fellows roost unnoticed and forlorn in studious seclusion ? Have the men who are selected as eligible canditates for fraternity membership better brains, better manners, better antecedents, than those who are not selected? It is more than doubtful. That they have a greater degree of superficial attractiveness must probably be admitted. Woe to the reserved man,thequiet chap, theimmature youth — his chance of unanimous description as a "dead one" is one hundred; his chance of a fraternity invitation, — just about zero. But the chances are that a fraternity made up exclusively of "dead ones" might shortly prove a power to be reckoned with.

Another peculiar feature of the fraternity situation is the relatively small number of fraternity members who realize the responsibility that their membership implies. They owe their election, let us hope, to the fact that something may rightfully be expected of them. They made a brave show up to the hour of pledging. After that, having won the prize, they settle back to bask in the radiant illusion that since the fraternity wanted them so badly, they have done it and themselves sufficient honor in joining.

But the tendency to estimate a prize as the ultimate and rest-inviting goal, instead of a mere milestone in the Marathon, is not confined to fraternity brethren elect. That it is somewhat generally characteristic of humanity was shrewdly pointed out by President Hadley of Yale, in his recent address to Harvard's scholastic prize winners. How is it, he inquires, that the public takes so little apparent interest in the winners of classroom honors, while the athlete never fails of his due meed of recognition. His answer may best be quoted in his own words:

"It is because people are willing to go anywhere, in any number, to watch the first public appearance of men who are likely to be the leaders and heroes of the next generation. The way to make the American people more interested in scholarship than in athletics is by proving that our prize scholars, even more than our prize athletes, represent the type of men for which there is public need. If our scholarships and prizes are so arranged that the prize is an end in itself, nobody, but the prize winners themselves and theirimimediate, friends, is likely to be interested. If the competitions are so arranged that the prize winners justify their selection by their subsequent life, then a college prize day becomes an occasion of moment to the nation."

This is a view of course open to some criticism ; but it possesses a sufficient element of truth to make it eminently and valuably suggestive. As a matter of fact the quality which inevitably demands and receives recognition is the quality of efficiency. When scholarship translates itself into terms of visible accomplishment, it seldom passes unrecorded. Scholarship which represents little but industrious accumulation is intellectual hoarding ; scholarship that directs itself to prize winning for what there is in it is akin to professionalism in athletics. To quote again:

"When, as sometimes happens, the money recognition is more than commensurate with the honor, it attracts competition of the wrong kind — competition of men who seek the money rather than the honor, and who are never likely in after life to do public service corresponding to the distinction which has been accorded them. We talk about the evils of professionalism in athletics. There is ten times more immediate danger from professionalism in scholastic prize winning than there is in all the intercollegiate contests with which Harvard and Yale are likely to have anything to do. A man becomes a professional when he enters into a competition designed to show what he can do, and uses it to see what he can get. It is this kind of professionalism which, to quote an expressive phrase of your president, has honeycombed our graduate departments ; it is this which constitutes the greatest menace to true scholarship in America."

One of the many delightful characteristics of Judge Cross is his ability, while clearly, often reverently, recalling the past, to yet live joyously and approvingly in the present. Hence his article on "Dartmouth College and the Class of 1841" in the preceding issue of the MAGAZINE assumes a double value, since it is not merely interesting as history, but illuminating as comparison. Two passages stand out as unusually suggestive to the perplexed latter day teacher: "I think the student who is well fitted for college in the best high and preparatory schools today is better educated and better prepared for a professional or business life than the graduates of college from 1837 to 1841." This smacks somewhat of criticism of that erudition which most of us assume crowned the brows of our grandfathers. Can it be that the present degenerate generation of football playing youths are doing more, gaining more in college than did their ancestors? It is a most disquieting thought. And further, if with no very considerable advance in the age of our students, we of the modern college faculty are trying to cram their craniums four years fuller than of yore, have we a right to complain if, somewhere in the hasty process, the packing is badly done ?

Again: "It was expected that every college graduate at that time would enter one of the 'learned professions', so-called, and it was considered unnecessary and a waste of time to ob- tain a college education for mercantile, manufacturing, or other business outside of the professions." In the good old days, then, men could interpret their college course in precise terms of professional preparation. With the advent of the future business man in undergraduate circles this condition has changed. Perhaps it is the large measure of inability to perceive the relation of specific courses to future activities that accounts for present low ideals of scholarship. Perhaps, then, the often desired elimination of certain superficial aspects of modern college life, disturbing as these aspects may be, would not reach the real root of the difficulty. Other, brand-new, equally alarming, and still more problematical manifestations might arise which would demand the invention of a further series of formulas as useless as the old. Why then risk taxing our ingenuity. Quite possibly it is better to endure the ills we have than to fly into the necessity for perpetual operations.

Ex-libris has received little attention at Dartmouth. A single exception, of the early period, is an engraved plate for the library of the Social Friends. It bears the design of a heart, supported by flowers, and surmounted with a figure of the sun, centred with a human face, while a scroll beneath carries the motto, "So/ sapientiaenunquam occidit." Some of these plates bear the name of "Noyes", but it has been impossible to fix the name of the engraver with certainty. A tradition that it was Nathaniel Hurd is to be doubted. With this exception, printed labels, sometimes bearing an impression of the College seal, generally have been used.

The Mellen Chamberlain bequest contained a provision for a bookplate. A design was drawn by Prof. F. G. Moore, and engraved by the late J. W. Spenceley. This plate, which has been much admired, has for its design an interior view from the Daurentian Library in Florence, surrounded by wreaths containing the names of the most illustrious librarians of the world. Professor Moore also designed a plate for the Lewisohn Fund, which was reproduced in halftone.

After various efforts to secure a plate for general use in the library, a design by the librarian was accepted, and was engraved by Mr. Spenceley. The aim of this design — which is reproduced in this issue — is to tell the story of the college" in heraldic language. On a background of pine needles and cones, suggestive of the forest origin of the early College, is placed the escutcheon of the College seal, drawn by Hurd, one of the early New England engravers, while at the four corners are the escutcheons from the Berkeley, Dartmouth, Wheelock, and Webster arms. The Berkeley shield is a suggestion of the intellectual and spiritual origin of the College, through the Bishop's efforts at colonial education, and his founding of the Berkeley Fund at Yale, of which Wheelock was one of the first beneficiaries, and which well may have inspired him to succeed where his benefactor failed. The Dartmouth shield suggests the material source of the College, while the Wheelock stands for the Founder, and the Webster for the Re-Founder.

The Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of Teaching, the object of which is to provide retiring allowances for professors in undenominational colleges and universities in the United States and Canada, has by reason of its relations with such institutions unequalled opportunities for collecting statistical and other material relating to higher education.

The second bulletin issued by the Foundation bears the title, "The Financial Status of the Professor in America and in Germany," and contains a mine of hitherto inaccessible information on this subject. The accompanying comments, which are incisive and at times of refreshing candor, gain much in weight the fact that they proceed from neither the administrative nor the professional circles of our colleges.

The study, so far as American conditions are concerned, is based on data furnished by one hundred and three institutions in this country and Canada, each one of which has an annual salary-roll for instruction of forty-five thousand dollars or over.

It appears that the average annual salary of a full professor in these institutions ranges from $1,350 to $4,788, but only eight institutions pay an average salary to their full professors of less than $ 1.800, and also only eight give an average of $3,500 or over. "Allowing for the varying numbers of professors in the different institutions, the average salary of a professor in the hundred strongest colleges and universities of America may be safely taken to be close to $2,500." The average age of appointment to a full professorship is found to be thirty-four years.

The bulletin rightly emphasizes the fact that in comparing the income of the full professor with that of the lawyer, the physician, and the engineer, the professor in these hundred strongest institutions must be regarded as the successful man in his calling. His income must therefore be compared with that of men in other professions who have attained at least an average measure of success. The average salary of a full professor at Columbia is $4,289 and at the College of the City of New York $4,788. In the opinion of competent men, according to the bulletin, the average good lawyer, physician, or engineer would be earning between four and five thousand dollars a year in New York at the age of thirty-four. But the income of the full professor is practically at a standstill, while that of the man in law, medicine, and scientific occupations rises in later life to ten, twenty, thirty thousand dollars. The same proportion will doubtless be found true for the rest of the country.

Thus far we have dealt only with average salaries. If the maximum rewards open to men of extraordinary ability are considered, it appears that only thirty-eight of the one hundred and three institutions announce a maximum salary of three thousand five hundred dollars or more. In five of these (Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Chicago, and Pennsylvania)the maximnm is fifty-five hundred or over. In the cities in which four of these are situated "a lawyer, a phvsician, or an engineer does not have to attain extraordinary eminence to receive several times the salary which is the utmost hope of the college teacher. Good, plodding men, who attend diligently to their profession but who are without unusual ability, often obtain in middle life an income considerably higher than a man of the greatest genius can receive in an American professor's chair."

The grade of associate professor, which in many institutions does not exist, carries an average salary of about 51,900. Only four of the forty institutions reporting this grade pay over $2,500, among them Harvard, which has the highest average, $3,400.

In the grade of assistant professor the average salary is about $1,600; the highest average salary in any institution is $2,719.

The variation between institutions in regard to the salaries of professors of all grades corresponds somewhat to the variation in the cost of living in different localities. A salary of $4,000 in New York may be hardly as good as one of $2,000 in some parts of the country. In general it is shown by the statistics that the salary of a full professor is not much above or below what the bulletin expressively calls the "line of comfort" in the locality in which he lives. The salary of an assistant professor, who usually has a heavy responsibility for the conduct of undergraduate courses, is with very few exceptions hopelessly below this line. In neither grade can a man in most cases support a family and live with that degree of comfort and freedom from financial worry which is necessary if he is to give the best that is in him to the institution by which he is emploved.

The bulletin considers that the two main causes of low salaries are the multiplication of small and weak institutions and the expansion of the curriculum over too great a variety of subjects. Fewer subjects, thoroughly taught by competent and adequately paid men would, it is argued, produce better educational results. The fact seems to be overlooked here that it is often desirable to stimulate scholarship by offering advanced courses, even if but few men take them. And again, it is doubtful if most institutions could materially reduce their teaching staff and thus increase salaries, by eliminating a few small courses, which are often given by an instructor at the sacrifice of time which would otherwise be at his own disposal.

In regard to the attitude of college authorities toward an increase of salaries the bulletin says : "If academic authorities approached their constituencies emphasizing that a college is really only its teachers, those teachers would not long be regarded as of less importance than buildings and athletic fields. But the providing of adequate salaries is generally the last item on the administrative program and the items ahead of it win at the teacher's expense."

The Carnegie Foundation has done much to free college teachers from anxiety concerning their declining years, and there are not wanting evidences that the authorities of the better institutions are becoming awakened to the economic necessity of paving the instructing staff sufficiently well to secure its thorough efficiency.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT TUCKER'S SPEECH AT THE NEW YORK ALUMNI DINNER, DECEMBER 8, 1908*

December 1908 -

Article

ArticleGEORGE TICKNOR AND THE COLLEGE LIBRARY

December 1908 By Sidney B. Fay -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1873

December 1908 By Rev.S. W. Adriance -

Article

ArticleCHINNING SEASON RESULTS

December 1908 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

December 1908 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1908

Article

-

Article

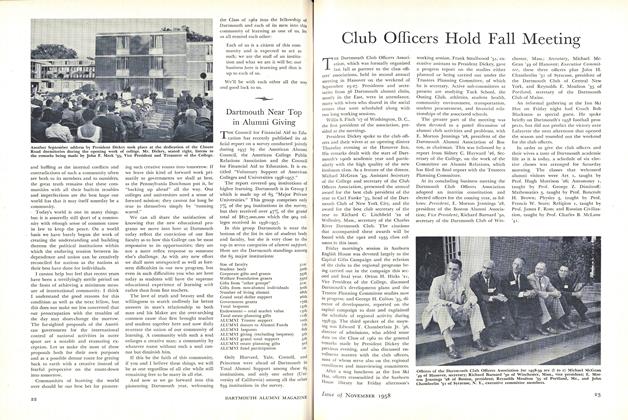

ArticleClub Officers Hold Fall Meeting

-

Article

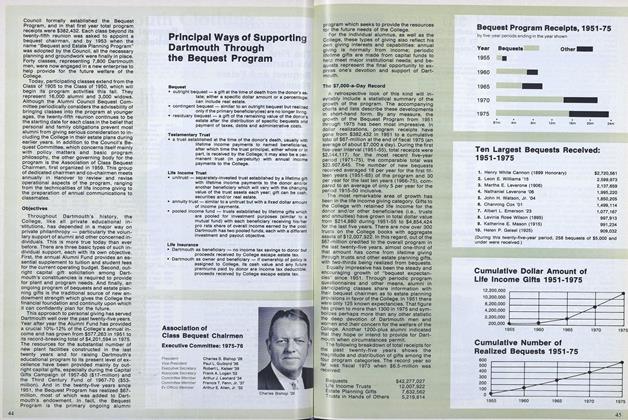

Article1975 Fall Reunions

September 1975 -

Article

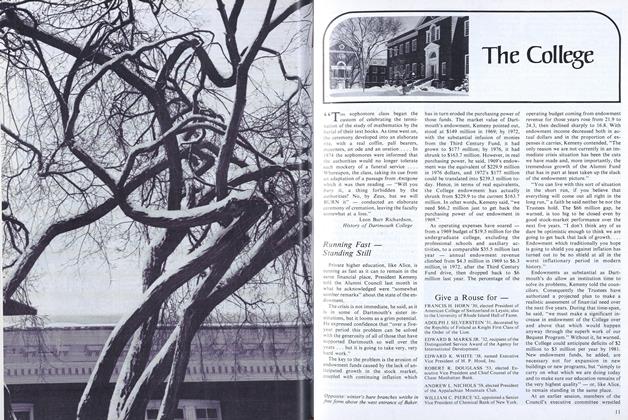

ArticleGive a Rouse for —

January 1977 -

Article

ArticleSOME CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDENT LIFE IN CAMBRIDGE

FEBRUARY, 1907 By G. F. -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

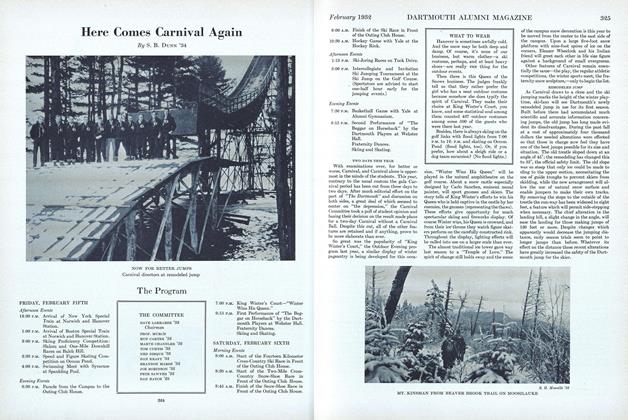

ArticleHere Comes Carnival Again

FEBRUARY 1932 By S. B. Dunn '34