The centenary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln was observed at Dartmouth in simple but impressive services in Rollins Chapel, Friday morning, February 12th. President Tucker presided, and introduced in turn members of the faculty, Mr. Lingley, Professor Bartlett, and Professor Wicker, who in the sincerity of their words and the succinctness of their tributes, held the appreciative attention of the College.

Mr. Lingley, speaking upon the simplicity of Lincoln, said :

The great statesman is ordinarily appreciated by a somewhat narrow circle of followers. The student of government cares to read the statesman's writings in order to estimate his effect on history and to study the working out of his theories. But the great body of the - people know only the name of the statesman and suppose in a vague sort of way that he must have been a great man.

The hold of Lincoln upon Americans has been of a different kind. The grip of his personality has reached the trained and the untrained alike. The flood of books about Lincoln which has come down upon us in the last few months is abundant testimony to the love of present-day Americans for the great president. The men of his day, too, were coming to estimate him at his true worth. The soldiers loved him and knew him as "Honest Old Abe" and "Father Abraham. " The Southern leaders, even, were getting an inkling of what Mr. Lincoln might mean to the South. General Sherman tells us that he was negotiating with General Johnston for the surrender of a Southern army when he received a despatch telling of the assassination of Lincoln. General Sherman read the telegram and handed it without a word to General Johnston. As the Confederate leader read it the beads of perspiration came out upon his forehead, for he realized that in the death of Lincoln the South had lost the one man at the North who was most inclined to be merciful to the Confederacy. But after all the most touching tribute of the people to Lincoln is the belief of the superstitious Illinois farmers who told Nicolay and Hay when they were writing their life" of Lincoln that the brown thrush did not sing for a year after the great president was assassinated.

Nobody would attempt to explain the hold of Lincoln upon Americans in a single phrase. The contrast between his earlier and his later career, the crisis which called him forth, and the tragic manner of his death, all helped to make prominent a man of many extraordinary characteristics. Of these characteristics a fundamental one was his simplicity. Whenever Mr. Lincoln faced a great problem he thought long and earnestly upon it, first that he might find the truth of the situation, and then that he might state that truth in the simplest language. This was, to be sure, but a reflection of the man himself, for Lincoln was one of the plainest and simplest of men.

A cloud of witnesses might be called to testify to Lincoln's simplicity of heart and of speech. Of the plain way in which he met the men who came to see him, the late Carl Schurz tells a good example. The great executive power which the president exercised during the war is well known. He could, for example, cause the arrest of any man from Maine to California, and cause his indefinite imprisonment without trial. In a word the president was a sort of military dictator. It was to a man clothed with such executive powers that Carl Schurz wrote a letter blaming the president because the war had up to that time been unsuccessful The president him to his office and bade him sit down. As he did so Lincoln slapped him on the knee and said with a smile, "Now tell me, young man, whether you really think that I am as poor a fellow as you have made me out in your letter. " Such a reception disconcerted Schurz. As he looked into the president's face he felt a big lump come up in his throat, but when he had regained his composure he told the president the criticisms which were being made of him, and the president told Schurz some of the trials and embarrassments under which he was working. And so the military dictator and the German soldier had an earnest talk of an hour and parted better friends than ever. Incidents such as this showed the people that dictatorial powers were safe in the hands of a plain man like Abraham Lincoln.

A good illustration of the simplicity with which he spoke to the people comes to us from 1858. Between 1850 and 1860 the country, was in a turmoil of debate over the restriction of slavery. One party claimed that Congress could constitutionally debar slavery from the territories, another party claimed that Congress could not do so, while yet a third thought that Congress should allow the people of the territories to settle that matter for themselves. Each party claimed that its plan would put an end to slavery agitation. Mr. Lincoln's prophetic speech in the midst of this turmoil is one of his simplest and most famous

"If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year since a policy was initiated with the avowed object and confident promise of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation not only has not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and .passed. 'A house divided against itself cannot stand.' I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved,—I do not expect the house to fall,— but I do expert it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other."

Some of Mr. Lincoln's letters to his generals were remarkable for their directness. A well-known example of this is the letter to "Fighting Joe" Hooker, giving him command of the Army of the Potomac:

"General,—I have placed you at the head of the army of the Potomac. Of course, I have done this upon what appears to me to be sufficient reasons; and yet I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and skilful soldier,—which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, —in which you are right. You have confidence in yourself,— which is a valuable, if not an in- dispensable quality. You are ambitious,—which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm; but I think that, during General Burnside's command of the army, you have have taken counsel of your ambition and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer I much fear that the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the army, of criticising their commander and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can to put it down...... And now beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but, with energy and sleepless vigilance, go forward and give us victories.

But the great monument to the simplicity of Lincoln is the Gettysburg address. Several states had purchased land on the site of the battle of Gettysburg for a cemetery which was to be dedicated in November, 1863. Edward Everett was to be the orator of the occasion and the president was to be called upon to say a few words setting apart the ground to its sacred use. Mr. Everett was well fitted for his task and for two hours he held the audience bound in the spell of his eloquence. The president then arose to perform his share of the ceremonies. It was a trying or deal. The simple little speech which Mr. Lincoln delivered took but two minutes in the saying and contained but twenty words of more than two syllables. Yet it is universally called a masterpiece and even today, more than forty-five years after it was delivered, it has a grip on our emotions. Small wonder is it that the next day Mr. Everett with fine courtesy wrote to Mr. Lincoln, "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes."

During the present week and for many weeks to come we shall hear much of Lincoln. We shall hear of the great role which he played in the drama of the Civil War and of the great complexity of the problems with which he dealt. But running through them all and fundamental in them all we shall find the simplicity of Abraham Lincoln.

Professor Bartlett followed, in description from personal recollection of the day of the assassination, and spoke further upon the growth of Lincoln's greatness. Mr. Bartlett said:

It was Saturday morning; and as I brought the newspaper from the door I read aloud the headline. "President Lincoln shot in Ford's Theatre." My father cried out as did many others that black morning, "My God, it can't I forgot that I had no breakfast and at once went down town where the bulletin boards by this time announced the death which had occurred at about seven o'clock. The streets were packed with humanity at the white heat of emotion,— grief, and immeasurable, power- less wrath from which little whirlwinds went forth to the swift undoing of a few who gave hints of ill-timed sympathy with the shocking deed.

As swiftly as the work could be done the city was draped in black.

The Easter Sabbath gave assurance that there was yet a government in Washington, but brought nothing to lighten the universal mourning. The churches were crowded, but not for their usual services. The minister came from the pulpit and sat with the people and m a few choked and broken sentences brought what comfort he could to a congregation who bowed their heads and wept whether he spoke or was silent.

About two weeks later, in the darkness of the very early morning in order to avoid the pressure of the vast throngs. I walked with my father to the court-house, and passing between the motionless sentinels whose watchfulness was over late, I looked upon the serene face of Abraham Lincoln. My father said I would be glad to remember it all my life.

And that evening, to funeral music that I have heard a few times since and that always brings to sight that torch-lit march, the body of the great president went to its entombment in Springfield, while his life went on to be the richest inheritance of the American people.

This was the city where the great Wigwam had re-echoed to the shouts approving his surprising nomination nearly five years before. Lincoln was a large man in 1860. His blameless character was established; he had debated with Douglas on the gravest national issues before as many as 20,000 hearers; he had shown discerning men in the East a little what manner of man he was by his addresses at Cooper Institute and elsewhere; and he had made the great choice between principle and policy, when, with full warning of its probable cost, he had in the senatorial contest gone on with the speech best known by the words, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot permanently endure half slave and half free;" but he was not the great man who, in 1865, with character ground exceeding fine in the mills not of the gods, but of God, with one stupendous task accomplished, and another before him, was suddenly caught from the sight of the people. In 1860 he was the favorite son of Illinois, Honest Abe, the Rail-Splitter; in 1865 he had become "Father Abraham" to a nation. His early call for 75,000 troops, in a war that enlisted nearly two and one half millions on one side, -fairly scales both men and measures of the earlier and the later days. When he entered upon his office it was the best hope of many that he might happen upon good advisers and be docile enough to accept their leading, but he discovered his own task to save the Union for the people and grew for it to such purpose and power that as the terrible days went by the strongest as well as the weak were ready to join in that poet's cry, "0, Captain, My Captain."

Three forces refined and remoulded him to the later Lincoin - his ever-growing reliance upon a God who revealed himself as be. nevolent but just, and active in the affairs of men, and to whom the distressed president went because, as be said, at times he had nowhere else to go; a colossal and slowly crushing burden of responsibility, which in its variety, its complexity, its ceaselessness, its cruel and needless chafing, can hardly be imagined by us now; and a sustaining current from and to the heart of the people. It was not the populace shouting and throwing their caps in the air, or clamoring for quick results that touched him,—though he always preferred them to shout for him rather than against him - but the people by their firesides thinking a matter out, and with slow, perhaps, but trustworthy consciences choosing the right and making the sacrifices the choice demanded —not the people of one section of the country, but all the people, whose children and children's children, as some of you are, should inherit and restore the storm-swept land.

He felt himself to be the servant of the people as thus defined, responsible to them as to a great personality, and on them as on a lesser providence he laid the essential decisions.

Mr. Lincoin's character, hardly clear to us now through a whole library of interpreters, was too unique and too many sided for well balanced contemporary analysis. And swift moving events were constantly disclosing new phases. While lawyers were showing the insufficiency of his authority this inexperienced provincial made himself dictator with full war powers for eighty days, till Congress ratified his acts. When his accomplished Secretary of State marked out for him a policy, and a ruinous scheme of foreign relations, those who had been questioning whether he had the discretion to follow good advice saw him wise enough even to reject bad advice from a good adviser. Those who raged at the setting aside of Fremont's manumission of the slaves in 1861 did not then know of the emancipation proclamation so soon to follow. His apparent flippancy often protected deeply stirred feelings. The deputation of Chicago ministers to whose annunciation of a divine command for emancipation he replied that it was strange it came bv way of the awfully wicked city of Chicago, had not then heard his statement that to God alone belonged the events that had controlled him, and they had blundered into the center of his soul where the decrees of a just God, his own personal feeling towards slavery, and his sense of duty to the whole country were warring together. And it is doubtful if that other shocked deputation to whom he replied by a request to know what whiskey Grant drank that he might send a barrel to his other generals, knew what heart-sick longings a soldier of Grant's qualities was fulfilling, or recalled the quaint scene at his home when the committee waited upon him to apprise him of his nomination, and bow, announcing his principles, he gravely treated them to a glass of good cold water.

Who could understand a president who began a most important cabinet meeting with a selection from a phonetic humorist, who would sit on the coping of the White House grounds to write an official order, or who, after repeated abuse of his patience and added insolence, seized a petitioner by the collar and lifted him out of the room ? What an incredible scene it was when as he the President of the United States wrote in his office an order for the release from the service of one of the two remaining sons of a widow, old and poor, she stood stroking his rough hair while tears ran down the cheeks of each.

He was elemental and the elements were rarely mixed in him. His patience with the needy and even the critical was nearly boundless; it stopped well within human limits with the obstructive; against the advice to save his strength he took his "bath of public opinion" as he called it, by hearing all who came, four times a week; he was masterful with men like Stanton and Grant and sympathetic with the humblest of the sorrowful ones who sought his aid; he was shrewd and simple; slow and hesitant when the situation made action doubtful; confident and unyielding in the ripeness of opportunity; ' wise for the future, as when he shared with Seward the unpopular surrender of the confederate commissioners taken from the Trent, held back the emancipation proclamation until the fulness of time justified it as a war measure, and turned a deaf ear to overtures of imperfect peace. He was hungry for the approval of the people and yet rock-fast to any principle to which his slow and accurate reason and his approving conscience had lead him. He was sore at heart at the cruelty and ravage of war, and unwavering in its prosecution. He called himself timid yet lived under constant threats of death with no outward sign of concern. At the time when he wanted most the approval of the people, politically, he imperilled it by ordering a new draft of 500,000 men, saying "What is the presidency worth to me if I have no country?" He was a thinker and a dreamer, yet had always ready his parable of homely life. Of nine months schooling, he had achieved the art of transparent speech and has left us masterpieces of thought and style. He never indulged in political or personal revenge; if he had animosites he hid them away and used men for their strength; he let no stinging word creep into his utterances to poison the concord for which he was ever hoping.

A man of these qualities was one who would grow into the love and trust of the people all over the land even if the qualities were only working their way to the light, and the character which was there was not yet fully formulated in words.

Large expression of the love never came until after his death, but the confidence was his when he needed it, never more manifest than when it swept like a tidal wave over the politicians who, in 1864, were determined upon his destruction.

Much nearer his time, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who can not be called over sentimental, these fine words of appreciation:

"He grew according to the need; his mind mastered the problem of the day; and as the problem grew so did his comprehension of it. Rarely was a man so fitted to the event. It cannot be said that there is any exaggeration of his worth. If ever a man was fairly tested he was. There was no lack of resistance, nor of slander, nor of ridicule. — Then what an occasion was the whirlwind of war! here was no place for holiday magistrate nor fair weather sailor; the new pilot was hurried to the helm in a tornado. In four years—four years of battle days—his endurance, his fertility of resources, his magnanimity were sorely tried and never found wanting. Then by his courage, his justice, his even temper, his fertile counsel, his humanity, he -stood a heroic figure in the center of a heroic epoch. He is the true history of the American people in his time, the true representative of this continent—father of his country, the pulse of twenty millions throbbing in his heart, the thought of their minds articulated by his tongue."

Professor Wicker was the last of the speakers, and spoke upon Lincoln as a practical idealist. Mr. Wicker said:

As mountain lovers eagerly debate the merits of different outlooks on some favored peak, so men to-day meet to exchange opinions as to what was the best, the strongest, aspect of the man Lincoln. And just as it is a distinguishing character of certain mountains that they present many interesting and beautiful aspects, so,as I think,is it a distinguishing mark of Lincoln.

To many he stands as an example of serious mindedness; to the world of the unlettered, on the other hand, I suspect that he is above all known for his broad humor. And both views of the man are just. "Fondly do we hope, fervently do" we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil-shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said: 'the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.' " Yet it was the same Lincoln who, in replying to a delegation from the National Union Leaeue, said of his recent second nomination to the Presidency: "I do not allow myself to suppose that either the convention or the League have concluded to decide that I am either the greatest or the best man in America, but rather they have concluded that it is not best to swap horses while crossing a river, and have further concluded that I am not so poor a horse that they might not make a botch of it in trying to swap. "

Lincoln was dignified: Lincoln was undignified. Again both views are right, according as you define your terms. If dignity lies in the unbending figure, the unseeing eye, the unsmiling face, and in pedantic restraint of phrase, then was Lincoln not dignified; but if dignity is a thing of the heart and mind, if it consists in sincerity and wholeness of vision and of purpose, then few ever had better title to dignity.

And so one might go on to multiply instances of varying, even of contrasting, aspects. But I wish especially to speak of what is at once an instance, and at the same time the finest result, of his many sidedness. I mean his practical, constructive idealism, especially as illustrated in his political life.

There is a bitter saying that a statesman is a dead politician; and the saying, though bitter, is so far true that in many cases time and death are needful before we can surely know whether the man was the one or the other. There were many who, in the lifetime of Lincoln, thought him a mere politician. I think that it was possible to know better even then. I feel certain that no one to-day, having full knowledge of all that he said, and wrote, and did, can or will deny that he was a statesman.

The word idealist is a much abused word. With some hesitation, I venture to define an idealist as one who finds his compelling motives in ideals whose objects are remote. Men tend to divide themselves into two groups : those who play the game of politics,— or, for that matter, the game of life, - for the game's sake or for immediately personal ends; and those who refuse to play the game at all, because to do so might mean the loss of some of their ideals. Lincoln was in neither of these groups.

He had ideals. It was because of his ideals that he entered into the great struggle at all. It was because of his ideals that he took advanced ground on slavery in the famous debate- with Douglass,- and his "house divided against itself" became later with Seward "the irrepressible conflict." It was because of his ideals that he was chosen candidate for the Presidency over many who were then supposed to know, better than did he, how to "play the game." It was because of his ideals that he put away all suggestion of unworthy compromise when the South answered his election with the threat of secession.

But he was a practical idealist. His ideals- had perspective; they had. balance. They were not to him of equal weight; of equal validity; of equal practical importance. He was always willing to sacrifice the less, if such sacrifice was necessary to attaining the greater. He realized that political achievement must wait upon political majorities; that political majorities are possible only when men will to sink lesser differences in the pursuit of a great end; and that he must in fairness be ready to lay by some of his opinions and wishes,— even to see them overridden,— if he would ask others to join him in fusing the many into political unity.

I think that it is not difficult to trace in his letters and speeches this perspective of ideals; this ordering of motives. His ultimate ideal was human progress. Only less important was his ideal of the American Union, with its Constitution. But that the Union and the Constitution were ideals of a lower order is evident from the fact that he more than once openly upheld the right of revolution. And as to the Constitution itself, he expressly declared his readiness to violate that instrument, if such an act were necessary to its preservation. Another of his ideals, early formed, cherished through life, was that of industrial liberty for all men. Lincoln hated slavery. He may well have hated it as bitterly as did John Brown. Yet, had the South not seceded, he would have resisted any attempt to abolish slavery by law, because in his view the Constitution forbade such a course. He would have preserved the Constitution as a chief bulwark of human progress and the American Union, confident that within it slavery must soon exhaust itself and be no more.

Much of this is evident in the well-known letter to Horace Greeley, called out by fault-finding that, in . another than Lincoln, would have passed the bounds of patience. I quote a part of the letter: "I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored, the nearer the Union will be to 'the Union as it was.' If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and t.he colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors, and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

"I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

"Yours, "A. Lincoln."

I have cited these ideals of Lincoln merely as illustrations of the usual working of his mind. What is true of him here is true of him throughout. It was his many sidedness that made him whole.

And so, I think, there is excellent political training, and training for the whole of life, in a careful, sympa thetic study of the man Lincoln. Nowhere will you more surely find incitement to adopt for yourselves, as the rule and guide of your faith and practice, that ultimate ideal of Lincoln, the ideal of human progress. and that due ordering of ideals which is necessary to their realization. To Lincoln, no other service is so great as that which urges mankind onward; nothing of the past is of practical importance, except as it lights the path up which our further steps must pass. May I then leave this thought with you, cutting it in words of Lincoln's own choosing, changed only as our need requires:

We have met to-day in memory of one who gave of the best of his thought and life to the task of making actual our forefathers ideal of liberty, fraternity, equality. And it is altogether fitting and proper that we should so meet. But he would wish that we should use this meeting, in the largest sense, in honoring the cause for which he worked, rather than in eulogy of him. His name and fame have a luster far beyond our poor power to add or detract. The world will not note what we say here. It is for us, the living, rather, to dedicate ourselves to the unfinished work which he so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the task before us,—that from his life we take increased devotion to those ideals for which he gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that he shall not have lived and worked and died in vain; that this nation, —and all mankind, shall have ever a new birth of freedom ; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDuring the first week of February public announcement was made,

February 1909 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

February 1909 -

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES' MEETING

February 1909 By W. J. TUCKER -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

February 1909 By WM. H. GAEDINER '76 -

Class Notes

Class NotesNORTHWEST ASSOCIATION

February 1909 By WARREN UPHAM '71

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRACK

February, 1912 -

Article

ArticleSome Books for Alumni Readers

November 1961 -

Article

ArticleDixon Appointment Makes Two '41 USAF Generals

October 1973 -

Article

ArticleVoce

February 1993 -

Article

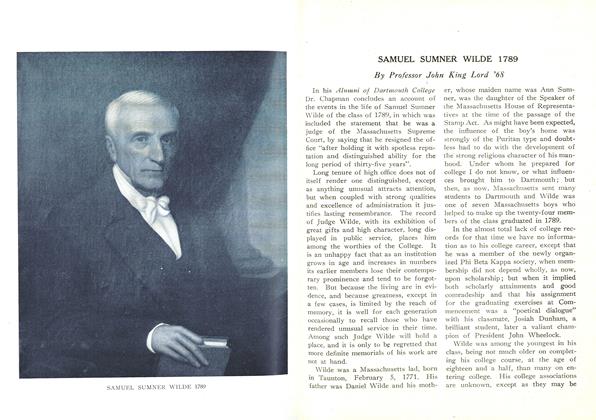

ArticleSAMUEL SUMNER WILDE 1789

March 1920 By John King Lord '68 -

Article

ArticleTallying the Alumni Fund

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49