in the dispatches from Washington, that the committee of the Trustees had formally asked Mr. Samuel W. McCall '74, to accept the presidency of Dartmouth College. Immediately following the statement of this fact, the press of the country with unanimity indorsed the action of the trustees and bespoke confidence in Mr. McCall's ability successfully to take up the duties of college administration, should he decide to transfer his activities from his chosen field in public life. During the time which elapsed from the first announcement until Mr. McCall's final letter, given to the press by Mr. Streeter upon its receipt, the hope constantly grew among Dartmouth men that the great opportunities of the presidency would suffice to induce Mr. McCall to undertake the responsibilities of the position. Under date of February twenty second, however, he wrote to Mr. Streeter, expressing his appreciation of the honor done him, and stated in detail the reasons which held him to the work which he had chosen, in which he believed it to be his duty to remain. The letter is as follows:

House of Representatives U. S. Committee on the Library, Washington, D. C., February 22, 1909

GENERAL FRANK S. STREETER,

Chairman of the Committee of Trustees of Dartmouth College.

MY DEAR GENERAl STREETER:

While I expressed to you my impression when you first mentioned to me the subject of the presidency of the College, yet its very great importance, the impressive manner in which it was presented, and the widespread interest in the decision, as shown in the many letters I have received from graduates of the College and from others, imposed upon me the duty of giving the matter my most serious thought. That duty I have made a sincere effort to perform and whether right or wrong I have reached a conclusion.

if I never had been at all connected with the College, I must yet have been stirred at the suggestion you have made me. There could be no greater distinction than to be thought of to lead one of the great intellectual armies of the country, to be associated with so noble a past and with such a splendid present in which the old and the new are so richly blended. But I had long known the charm of Hanover, so beautifully seated among the hills and so completely dominated by the college spirit as to make it, one might fairly say, the most characteristic college town in America. No one could be more sensible than myself of both the attractiveness and the distinction of the proposal, the value of which was enhanced by the fact that I had been thought of by a board of trustees who personally knew me and containing among its members two of my classmates with whom I had been bound by ties of intimacy since we were boys together at Hanover.

The chief work of my life has been only in the most general way related to education. One's habits of thought tend to become fixed and more or less adapted to the pursuit he is engaged in and he should hesitate before transplanting himself to a new field. The difference in the work I have been doing and that you propose may not really be one of kind and I should not wish upon that point to set my opinion against your own and that of President Tucker, who is a master in his calling, and is giving an administration, in brilliancy conspicuous in the history of colleges. And to decide upon that ground too would be merely to take the view of caution and conservatism, something scarcely to be thought of when there is an influence more positive operating upon my mind.

The work which I am trying to do was not entered upon by accident and if I have not pursued it with success it at least is not because my vows were lightly taken. And since I did not lightly take it up I cannot, in what I believe to a very grave crisis, drop it easily and shift to something else. I may be accomplishing little of value, but I should indeed be a sorry soldier nicely to weigh causes and to decide at this moment to step out of the ranks. This is not the place for political discourse but perhaps I should say to you that the crisis I refer to is in my opinion full of peril to our institutions and how soon the movement is to begin towards sanity and safety Ido not know. I am far less concerned by particular theories than by general methods of government—methods which have been carrying us swiftly towards a condition under which limitation upon governmental power would be done away with and the favoritism and caprice of an autocrat would take the place of constitutional restraint. And some chance barbarian as an autocrat might overturn our temples and do more harm in the direction of uncivilizing the country than all our colleges together could possibly repair.

It may be that I have an exaggerated notion of the relative importance of my present work but if so the teachings I received at "the college on the hil" must bear a part of the responsibility. Her traditions are vital and throbbing with inspiration to public service. I need only mention to you the supreme causes of constitutional stitutional government and the preservation of the Union. With both of those causes her name is imperishably identified.

government and the preservation of the Union. With both of those causes her name is imperishably identified. I have decided therefore to continue in the service of the most tolerant and generous of all constituencies, which has just honored me by a re-election to Congress, and accordingly I ask that you do not consider my name when the time comes to choose a President.

In conclusion let me say that I should deem myself a quite unworthy son of Dartmouth to deny her anything that would help her and that she might fairly ask, but I cannot, but think my decision the wiser one even for her. She has sons highly fitted for her service, skilled in administration, with a special training and scholarship to which I can lay no claim, and under some one of them she will continue to grow and prosper. Planted even before the nation was born, she has been through every crisis of our history, has had her own special stress of storm and has emerged from every trial more lovely and more strong until today she is confronted with no grave problems unless with such as prosperity often imposes. Those problems whatever they may be will trouble her but little, when she comes to face them, as she surely will, her heart filled with the great memories of her past and her fair eyes looking hopefully upon the future.

Sincerely yours,

S. W. McCALL

A spirit of educational unrest seems to be moving throughout the civilized world. Though the problems vary in different countries, the is everywhere manifest to criticise existing systems and institutions as either inefficient in themselves or ill adapted to the needs of the age.

In this country the college, the most specifically national element in our whole educational system, is being subjected to a searching examination. As typical of the movement for reform may be taken a recent book by Abraham Flexner, "The American College, a Criticism " (The Century Co.). Mr. Flexner proceeds from the assumption, which is pretty generally acknowledged to be true, that our colleges are not giving the great majority of their students the thorough training and sound foundation of knowledge which they 'ought. Between the attitude and resources of the college and the product which it turns out there is a startling incongruity. "On the one side, a formidable array of scholars and scientists, libraries, laboratories, publications; on the other, a large miscellaneous student body, marked by an immense sociability on a commonplace basis and widespread absorption in trivial and boyish interests. How are we to account for the disparity?"

The beginning of evil Mr. Flexner sees in the fact that the college pays no attention to elementary education, but on the other hand rigidly prescribes what and how the preparatory school shall teach. From the point of view of the latter, education thus becomes a matter of fitting pupils to pass entrance examinations. There is no time left for drawing out and developing the capabilities of the individual, which should have begun in the elementary and been continued in the preparatory school. After a prescribed grind of four years the student comes face to face with the elective system. How is he to choose wisely? Some colleges give him a little perfunctory advice, others restrict his choice within certain limits or do not throw open the door of free election until sophomore year. All these devices avail little, however, for the student's individuality is undeveloped and a really purposeful choice therefore impossible. The student elects wildly, not forgetting snap courses. Thus the rigid prescription of preparatory work defeats the object of the elective system—the education of the student along individual lines.

Mr. Flexner may with pardonable zeal overestimate the function of the school as compared with the family in arousing a serious purpose in life, but it is nevertheless true that the present relation between college and preparatory school produces a more or less violent break when there should be educational continuity. The harmful effects of this break are, however, reduced to a minimum in institutions which like Dartmouth, require the student to continue in his first year certain studies which are offered for admission. The value which experience has shown this arrangement to possess is not properly appreciated in the present book.

Mr. Flexner is not an opponent of the elective system in the sense that he would return to the old prescribed course or reduce the number of branches of knowledge which can be pursued in institutions of college grade. But he does demand that the system be differently employed.

The instruction in colleges is next taken up, though the consideration is practically limited to institutions in which a graduate school has been superimposed upon a college of liberal arts. A strong case is made out against the presence of graduates and undergraduates in the same courses, against the diversion of money and energy from college to graduate school, and against the lecture system with its corps of assistants unskilled in teaching. Since in such institutions the president is too busy and the dean otherwise engaged, it is suggested that a new official be appointed to have general oversight over instruction. There is no doubt that Mr. Flexner has here touched the weakest spot in our colleges today: the lack of adequate, efficient instruction, adapted to the needs of the normally intelligent youth of college age. And the greatest neglect in this respect is to be found in the large universities.

In his last chapter, "The Way Out," Mr. Flexner attempts to point the way to a better state of things. As for the relation between the preparatory school and the college he says: "The examination system cannot be at once wiped out; but it can be gradually reconstituted. Entrance to college can, whenever the colleges so desire, be treated as a privilege. The range, seriousness, and cohesiveness of previous study may be made the main factor in deciding to which of the excessive number of applicants further opportunity shall be extended." A higher standard of actual attainment in preparatory work is thus demanded than the one now in force.

Under the new conditions the preparatory school has already "laid bare the individual, has started up vital and characteristic activities, the college has something to build on." The student is supposed to know what his object in life is to be. "The college must then organize for him the intermediate steps to his chosen end. For this purpose it is worse than useless to maintain a diffuse and practically endless course of study. A compact, related, and organized body of instruction in each of the fields which the college undertakes to cover, must be substituted for the disjecta membra of the present catalogue." It might be objected that this plan involves beginning vocational or professional training, i.e. specialization, too early.

If the vocational work is begun early, however, there is plenty of opportunity to pursue a liberal training at the same time, resulting in a broad but consistent college course. Under the present system two or three years may be wasted in aimless electives and then be followed by intense specialization without a proper basis.

Finally a plea is made for the establishment of institutions outside the present ones, where problems in education may be worked out. One may differ from Mr. Flexner's ideas in detail, but the substantial truth of his main contentions can hardly be called in question. Not the least significent thing about the book is the genuine enthusiasm for the college as the dominating factor in American education.

The most maligned institution at Dartmouth is the winter season. By a majority of the undergraduates it is looked upon distrustfully as a period of enforced and very unexciting hibernation: by the faculty it is merely tolerated by virtue of a traditional hope that its dreariness may turn the student —as a last resort—to his books. Not many have realized that in its long, white winter Dartmouth possesses a valuable asset, almost unique among eastern colleges. Variably, to be sure, Boreas, who grips us early in December and seldom loosens his hold until March is well advanced, provides us at our doors the things that city folk journey miles to find : skating, sleighing, tobogganing, skiing—all the sports that ice and snow afford. It may be that the success of the college hockey team has in some measure increased an appreciation of these things : certainly an unusual number of enthusiasts has this year made Hanover's surrounding hills populous with ski and toboggan parties. This is most encouraging : in fact, some keen observers are beginning to argue that, for novelty of entertainment, February offers opportunities unknown to May, and that a prom week in snowdrift time might easily prove more attractive then the one held during the presumably more romantic days of spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleLINCOLN MEMORIAL SERVICE

February 1909 -

Article

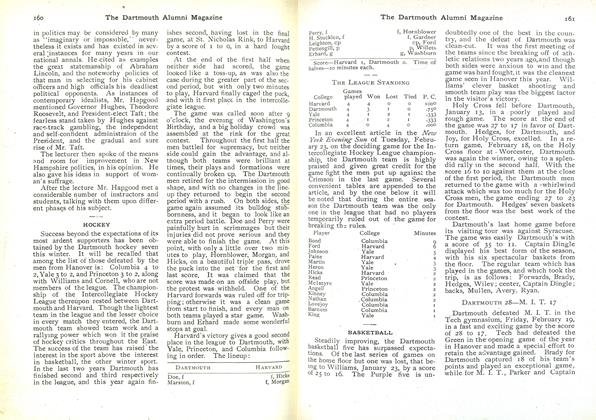

ArticleBASKETBALL

February 1909 -

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES' MEETING

February 1909 By W. J. TUCKER -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

February 1909 By WM. H. GAEDINER '76 -

Class Notes

Class NotesNORTHWEST ASSOCIATION

February 1909 By WARREN UPHAM '71

Article

-

Article

ArticleKIRKLAND '16 DECORATED FOR BRAVERY

March 1918 -

Article

ArticleOnly Twenty Years Ago

April 1934 By Charlie Griffith ' 15 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

APRIL 1973 By J. J. ERMENC -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND THE CHURCH

January 1922 By JOHN KING LORD '68 -

Article

ArticleMEN OF DARTMOUTH

MARCH 1997 By Mary Stewart Donovan '74