the complete proceedings of the Inauguration of President Nichols will be published by the College. Meanwhile the ALUMNI MAGAZINE has pleasure in printing the President's address and the cornerstone address of Professor Bartlett. All that was said on this day should be read by every man of the College, — but these especially!

In the spring of 1907. after a decade and a half of work in co-operation with a beloved leader, the Trustees of Dartmouth College were suddenly called upon to face the greatest of a multitude of large responsibilities which had been theirs in recent years. President Tucker had resigned because of failure of health, and had asked for early appointment of a successor. In accordance with the urgent and reiterated request of the Board, he at length agreed to remain in office until such time as the Trustees should be able, without haste, to study the educational field, and to make choice of a president for Dartmouth with full knowledge of the qualifications of the men from whom choice should be made, and with soberness of judgment as to what qualifications should be considered vital.

From early in the quest, the Trustees turned again and again to the name of one, the initial confidence in whom grew even still larger and stronger the more his work and his sentiment became known. And when in the fulness of time election was to be made, the Trustees gathered without division of judgment, and with enthusiastic unanimity elected Ernest Fox Nichols, who was inducted into the Presidency of Dartmouth College on October fourteenth.

At this time no comprehensive review of the past is necessary, nor is any adequate survey of the future possible or even desirable. But here and there a fact appears which invites renewed statement.

Dartmouth College has completed one hundred and forty years of corporate life, under a charter of remarkable sort, which still justifies Mr. Webster's praise, that '"a charter of more liberal sentiments, of wiser provisions, drawn with more care, or in a better spirit, could not be expected at any time or from any other source." According to this charter "in the case of the ceasing or failure of a president by any means whatsoever the said Trustees shall elect such qualified person as they shall think fit to be President of Darmouth College to have the care of the education and government of the students." It is to all the multiform responsibilities and opportunities covered by this phrase that the Trustees have elected Dr. Nichols as the "qualified person whom they deem fit to be President of Dartmouth College."

The College in the modernization and evolution of recent years has been strengthened and made confident by the closer grouping and affectionate devotion of the hundreds and thousands of her sons which has come to be known as the alumni movement. Through the new zeal of this loyalty among Dartmouth men progress has been made which otherwise would have been impossible. Moral support has been given to the insistence upon the highest ideals and standards ; material support has" been given to the rebuilding of the plant; and individual support has been given by every Dartmouth man to what he conceived to be the best interests of the College, whenever opportunity has offered":

The interest and co-operation in behalf of the College which has grown up as a result of organization and intimacy of the administration with the alumni of the College is to-day one of its strongest assets. And the statement made by Mr. Streeter at the Inauguration, in behalf of "the Trustees, would not have been complete if he had not said that they had knowledge of Dr. Nichols, that though an adopted son of the College, he was in appreciation of the fellowship of the sons of Dartmouth and in devotion of sentiment toward the College not to be distinguished from Dartmouth's own sons. Indeed, it should be further said that this knowledge of his pride in his relationship to the College and its graduates was of vital import to all members of the Board of Trustees, of whom five hold membership through nomination of the alumni, and that in this together with knowledge of the quality of his scholarship and his administrative ability enthusiasm was engendered in the Board even as for a Dartmouth man in course.

It is impossible to forecast the problems that are to arise for settlement by American colleges in years to come. It is likewise, too, impossible to know the opportunities that lie before. Plainly the Trustees of the. College have no wish nor even willingness, in ignorance of conditions which may arise, to dictate a policy upon which to insist, perhaps to future harm. Their fundamental policy is that the development of the College shall be under the guidance of those who love her life and her traditions, and have efficiency meet for the opportunities which may appear. To the new President, whom they know to embody these qualities, they have intrusted the leadership in full confidence for the future of the College whose interests are to their hearts, and to the hearts of all Dartmouth men, of vital concern.

The exercises of the day of the Inaugural were not only an auspicious beginning ]for the new administration, but they were also the constituents of an academic event of grade conspicuously high. By testimony of many of the delegates, written in terms of unusual warmth, the day to them was one of consequence and pleasure. For the College the' significance was greater probably than can be appreciated fully. The advantages of coming into personal contact with the most modern educational thought and discussion are manifest. Hardly less important was the opportunity of knowing co-workers and being known of them within our own gates. It afforded genuine pleasure to hosts that guests in Hanover found so much that interested them.

The events of the day were carried through with full dignity of academic ceremonial, but yet with simplicity and naturalness. The heartiness of the confidence of the retiring administration in the new was equalled by the respect and affection of the newly inaugurated president for him who relinquished his trust. Herein was the human touch,— a delight to all.

Perhaps no utterance has been more eagerly awaited at Dartmouth, certainly not in recent times, than the address of President Nichols. And the satisfaction that it gave to sons of the College in its proof of love for those things which Dartmouth men hold dear was equalled by the conviction of those from away that the onward march of the College would be without a halt and under the direction of a leader of wisdom and of force.

The spirit of the exercises of the afternoon was well expressed by the President at the laying of -the corner-stone of the new gymnasium, his first official act after his induction: "In the name of God the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, I declare this stone to be the corner of a house devoted to that training of the body which shall make it the sturdy and obedient servant of the mind and spirit of man." The program was under the guidance of that member of the alumni whose time and strength have so conspicuously been at the service of the College, and whose untiring activity is responsible so largely for the means wherewith to build the greatly needed new gymnasium. The address was by him of the faculty who with all his other work has yet made himself preeminent in all that concerns strong bodies and clean sport. The history of the conception and evolution of the plans was given by him with whom they originated. And inspiring all and surrounding all was the enthusiasm of the student body.

Again, the evening was of especial delight. Nearly five hundred sat down to to the dinner in College Hall. Distinguished delegates, guests, and alumni from all parts of the country assembled. The representative of the Trustees who presided was .at his best, and academic discussion has rarely reached as high a level as it reached in this, the closing event of a memorable day.

On October sixth Dr. Abbott Lawrence Lowell was inaugurated as President of Harvard University. Eight days later, Dr. Ernest Fox Nichols was inaugurated as President of Dartmouth College. It is but natural that the inaugural addresses of these two men, the one undertaking leadership of America's most venerable university, the other that of its largest college, should have been awaited with interest by the educational world as providing opportunity for comparison and contrast of proposed policies in the government of a great university on the one hand and of a great college on the other. To some, therefore. President Lowell's address may haVe caused a degree of disappointment; for, studiously avoiding the large aspects of the problem before him, he confined himself to that presented by the college, and particularly by Harvard College. To those, however, who look upon the college as a most essential part of the country's educational fabric, and who had feared its elimination in favor of the university, President Lowell's attitude must bring optimistic satisfaction. Further, the similarity of his theme to. that of President Nichols, gives opportunity for interesting comparison if not for strong contrast.

On the whole, President Lowell seems less optimistic than President Nichols: He feels that "college life has shown a tendency to disintegrate both intellectually and socially." There is something here of implied yearning for the things that were. President Nichols feels this less keenly. "Any dissatisfaction with college life does not find its basis in comparison with earlier years," he says. "We are not quite satisfied with, the college because it does not realize our later ideals of education, not because it falls short of earlier ones." Yet he agrees with President Lowell that the intellectual standards of the undergraduate are lower than they should be, though he suggests somewhat different causes for the condition; agrees with him, too, in laying part of the blame for the uncertain educational standards of the past quarter century upon the transition from the old, restricted curriculum, to the later, more or less unrestricted one. President Lowell »elaborates at some length an ideal course which should ensure to the student mastery of some one subject and reasonable acquaintance with a number of others. Here again he and President Nichols are in agreement, though while one suggests a goal to be sought, the other points to the "group system" as an accomplished fact. As to the means to the desired end of making studies vital to the undergraduate, both men lay some stress upon the small class and the intimate relation between instructor and student.

So much for the comparison of isolated opinions; in general plan the two addresses are quite unlike President Lowell begins by granting that the present day college is in many ways defective, and frankly points out its defects. Having so done, he outlines his ideal of what a college should be, particularly with reference to the end which it should achieve, and then, naturally, suggests the means to this end. President Nichols deals with his subject perhaps more concretely. Speaking from a twenty years' experience as a teacher, he waives the specific problems of Dartmouth in favor of the problems of the college at large. Briefly stating his conception of the function of the college, he considers the three elements chiefly concerned : . the curriculum, the student, the teacher. Each of these three he examines critically in its present aspects, defends its virtues, points out its weaknesses, and suggests measures of improvement

But whatever the differences in the plan of their addresses, both Presidents voice a similarly high ideal in their closing words. Says President Lowell:

"A greater solidarity in college, more earnestness of purpose and intellectual enthusiasm, would mean much for our nation. It 'is said that if the temperature of the ocean were raised the water would expand until the floods covered the dry land; and if we can increase the intellectual ambition of college students the whole face of our country will be changed. When the young men shall see visions the dreams of old men will come true."

Says President Nichols: "Sound learning, wisdom and morality are the foundation of all order and progress, and these it is the aim of the college to foster. If we can send into the world a yet larger number of strong young men — men clean in body, clean in mind and large of soul, men as capable of moral as of mental leadership, men with large thoughts beyond selfishness, ideas of leisure beyond idleness, men quick to see the difference between humor and coarseness in a jest — if we can ever and in increasing numbers send out young men of this sort, we need never fear the question — 'Can a young man afford the four best years of his life to go to college?' "

For those subscribers to THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE who preserve their files, an index has been published for the volume for 1908-1909. This will be sent to any subscriber, upon application.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS

October 1909 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS AT THE LAYING OF THE CORNERSTONE OF THE NEW GYMNASIUM

October 1909 By Edwin Julius Bartlett -

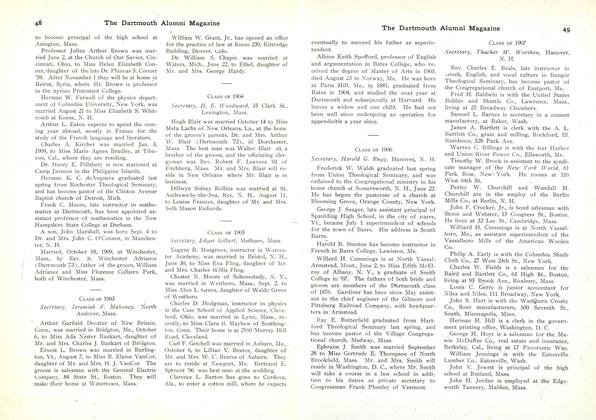

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1844

October 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1907

October 1909 By Thacher W. Worthen -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

October 1909 -

Class Notes

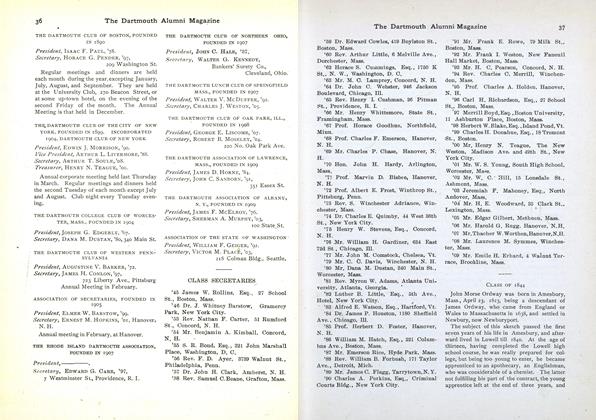

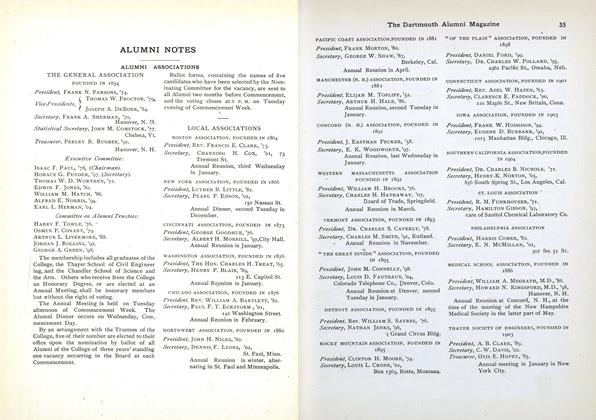

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

October 1909

Article

-

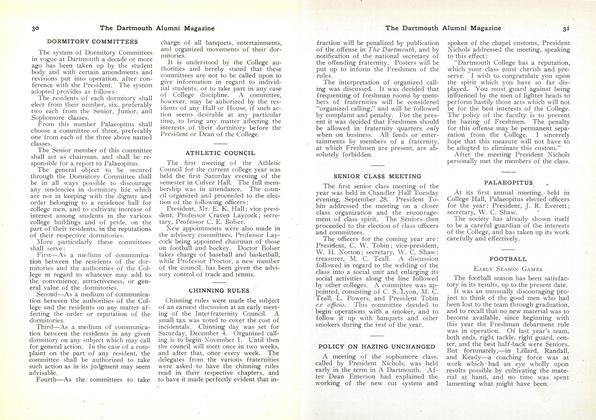

Article

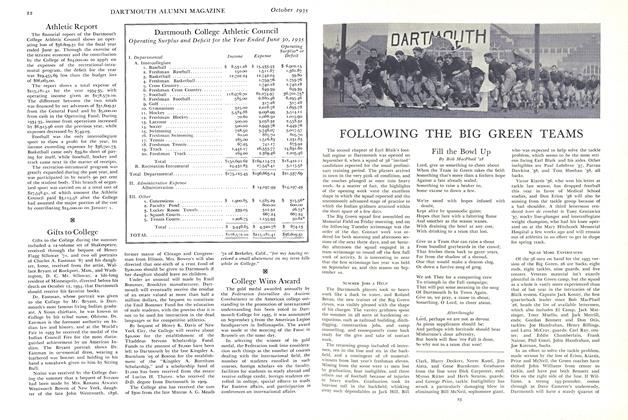

ArticleDartmouth College Athletic Council

October 1935 -

Article

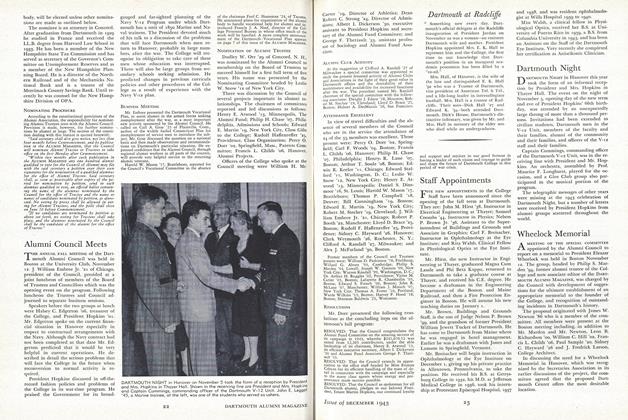

ArticleWheelock Memorial

December 1943 -

Article

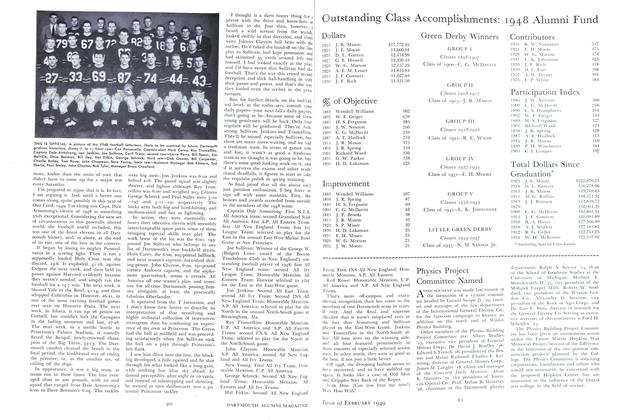

ArticlePhysics Project Committee Named

February 1949 -

Article

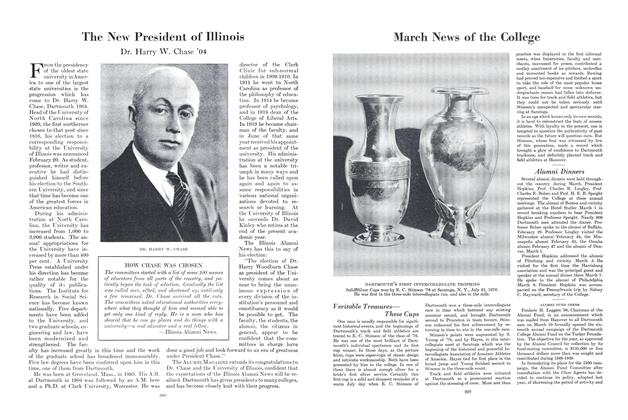

ArticleThe New President of Illinois

APRIL 1930 By Dr. Harry W. Chase '04 -

Article

ArticleMan of Dartmouth

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53