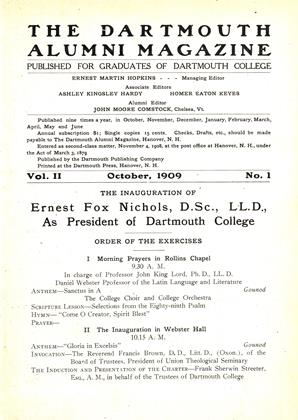

The past sixteen years have been and ever will be notable years in the history of Dartmouth College. In that time the number of students has all but quadrupled; and the material equipment of the College has expanded in proportion. The College has added to its libraries, built laboratories for its scientific departments and modern dormitories for its students. Its teaching staff has grown in size and advanced in quality. In every direction the growth of. the College has been rapid and great, but at the same time normal and balanced. The student body has changed in more ways than numbers, for if we believe with William of Wyckham, "that manners maketh man," and to a very considerable extent they undoubtedly do, Dartmouth is not only graduating more, but a better average of men than in earlier times. Dartmouth's development in these years has been due in an extraordinary degree to the work of a single leader, arid that leader is Doctor Tucker. His winning, alert, and earnest personality, his wisdom, foresight, and his moral, mental, and physical energy, have carried the College forward over many obstacles which to others, at the time, seemed insuperable, and so they might have been under other leadership. The College has been truly blest with an intrepid and farsighted pilot who has brought her safely over rough seas and through some narrow and dangerous channels. The College, the State, and the Nation have just reason to take pride in Doctor Tucker s great achievement.

„ That grave problems still face the College is but evidence that Dartmouth is thoroughly alive, for in death only are all problems solved. It is not, however, of Dartmouth's individual problems that I wish to speak today—l am not yet sure I know them all. I want rather to speak of some of the problems common to all our American colleges, and ask permission to speak of them not as an administrator, but as a college teacher—a calling in which I have some background of experience.

The college is the latest phase of the institutional life of our country to -be assailed by the reformer, and it cannot be denied that we have been unfortunate in some of those who have hurried in to tell us our faults. All angles of the complex problem are gradually coming into view, however, and the public once awake may be trusted to do its own thinking.

To open the whole subject in one address is manifestly impossible, yet there are some fundamental matters here which should be better understood. I shall speak briefly first of the place and intention of the college in our American education and later on certain aspects of the curriculum on undergraduate life and some of the problems of teaching.

The college rises on the finished foundations of the secondary school and leads to the professional and liberal departments of the university on the one hand and directly into the open fields and the branching highways of life on the other. It offers a quiet space for the broadening, deepening, and enriching of the mind and soul of man, a home of mental industry, and moral growth, a season for "the austere and serious girding of the loins of youth," and an inspiration to that other life of refined pleasure and action in the open places of the world.'

To those approaching graduate studies the college should offer those fundamental courses which serve as points of departure for the higher branches of theoretical and practical knowledge pursued in the university. To all it should give sound training in those analytical powers of reason upon which sane judgment must ever rely for its validity, and it should offer that knowledge of economic, social, and political problems essential to enlightened and effective citizenship. The college should aid its students to understand what man is today by filling ill the background, physical, mental, and spiritual, out of which he has come in obedience to law. The whole current of college life be so directed as to foster the finer qualities of mind and spirit which give men dignity, poise, and that deeper sense of honorable and unselfish devotion to the great and common good.

Whatever knowledge and trained faculties a student may have acquired at graduation depend more upon the man and less upon the college. Colleges may provide the richest opportunities and the fullest incentive, but that which lies beyond is work the student must do in himself. College, like life, is whatever the man has industry, ability, and insight to make of it. "They also serve who only stand and wait" was written to console, blindness and advancing years, not as an apology for strength and youth.

The Curriculum

To attack the curriculum seems to be an easy and rather stimulating task for most reformers, but to grasp its whole significance and deal fairly by it require more thought and pains than many a magazine or newspaper writer is accustomed to give to the things he so often whimsically approves or condemns. To understand the recent history of our colleges, from any point of view, the intellectual development of the world during the past half century must be taken into account as well as the rather lagging response which has come from school and church to its widening demands.

The middle of the last century saw the beginning of several intellectual movements. Natural Science got under way earliest by establishing the doctrines of evolution and energy. The bearing of these broad principles soon became as necessary to our modes of thought as they were immediately recognized to be for our material development. Today there is no branch of knowledge which has not in somewise been extended and enriched by the philosophical bearing of these wide sweeping laws which, at first, were the individual property of Natural Science. So intimately have they become the guiding principles of all modern constructive thinking, that steer how he will the man in college cannot escape their teachings. Although these principles are still most significantly presented in the laboratories in which they arose, the student will as surely find their progeny in Philosophy and History, in Theology and Law.

The progress of half a century in the social sciences (history, economics, sociology, politics), has been of equal importance. Though no such fundamental and far reaching doctrines as those of evolution and energy have there been discovered, yet social studies have become vital to the interpretation and upbuilding of modern life and service. •

What response did our colleges make to this revolution in thought, this sudden widening of intellectual and spiritual horizons, this modern renaissance? For a time practically none, for the curriculum was strongly entrenched m an ancient usage. Something called a "liberal education" was a kind of learned creed. The intellectual atmosphere outside the college grew broader, stronger, freer than m it. Forced by a rising tide, the colleges first made a few grudging and half-hearted concessions, but still held for the most part firmly to their creed. The defenders could always point in unanswerable argument to the men of profound and varied talents who have been trained under their discipline,— a discipline which all must freely admit has never been excelled. But times had changed, professional schools and real universities had come into existence in America, and more kinds of preparation were demanded of the college. Modern life in its vastly increased complexity had outgrown the straightened mould of a clerical, forensic, and pedagogical curriculum.

Finally in an awakened consciousness some colleges made the mistake inevit- able after too long waiting, and not only established the newer subjects in numerous courses, but took the headlong leap and landed in a chaotic elective system.

Under this unhappy system, or lack of system, for every student who gams, a distinct advantage by its license, several of his less purposeful companions seek and find a path of least resistance, enjoy comfort and ease in following it, and emerge at the other end, four years older, but scarcely more capable of service than when they entered.. Many another youth, neither lazy nor idle, but lacking both rudder and chart, angles diligently in shallow waters, goes no deeper than the introductory course in any department, comes out with many topics for conversation, but no real mental discipline and but little power to think.

During the revolutionary period in our colleges, in which the newer studies took equal place along side the older ones, Dartmouth moved more circumspectly than some of her sisters. In response to pressure from within and from without, required courses were reduced in number and crowded back into freshman-year. All other courses were grouped in logical sequences among which the dent had for every useful purpose all the freedom afforded by what I have called the chaotic elective system; but obstacles and hazards which required some serious thought and discipline to surmount were strewn in the path of least resistance. The incomplete angler also was compelled in some places to go deep enough to get the flavor of several branches of learning and acquire some sort of discipline.

Under this so-called group system, which has taken many forms in different colleges, our education is become liberal in fact as well as in name (the newer studies may be followed for their own sake as well as the older ones), and the college horizon has been vastly widened. The older and newer knowledges now stand on a footing of complete equality of opportunity, our education has caught up with the time and is in harmony with modern needs. Moreover the frame- work of the present curriculum is elastic enough to easily adapt itself to any changed conditions which may later arise.

In all this readjustment, many advocates of the classics have, it seems to me, been somewhat unduly alarmed and have lost sight for the moment of some of the sources of greatest strength in classical learning. They have emphasized the discipline of classical studies too much, and their charm too little. The undergraduate of today will not shirk disciplinary studies if he can be made to see definitely whither they lead and that the end is one which appeals to his understanding and tastes. He refuses to elect courses which are only disciplinary or are so represented.

The classics are as truly humane today as they ever were. Scientific studies have exalted observation and reason, we are gaining a sudden and surprising insight into nature and into social problems. We have grown in constructive imagination and the power to think relentlessly straight forward, but the vision has been mainly external. Spiritual interpretations embodied in the nobler forms of artistic expression, in music, in poetry, in art, have not kept pace with our purely intellectual progress. It was in a genius for adequate, free and artistic expression, it was in imagination, in poetry, in consummate art, and an exalted patriotism that the classic civilizations were strong. They had that in them to which man with a clearer insight and finer appreciation will one day gladly return. Their literatures give the fullest expression to the adolescence of the race, that golden time when men were boys grown tall, when life was plastic, had not yet hardened, nor men grown stern. Truth, Beauty, Goodness were still happily united; men did not seek them separately, nor follow one and slight the rest. Even philosophy with Plato was poetic in conception, and rarely smelt of the lamp.

Some of the deeper experiences of the race cannot be justly characterized as either true or false because they have no place in the logical categories, hence unfeeling reason cannot wholly find them out nor utterly destroy them. Much confusion and harm have come to man's most vital concerns through loss of balance and failure to recognize limits to pure reason as we now know it. Many a Soul has been beaten back or shrunk by rejecting all impulses which could not be explained or fitted into some partial scheme of things. In this both science and theology, in different ways, have at times offended. Both with an assumed authority have marred the spirit by attempting to crowd it into the frame of a procrustean logic or to square it with a too rigid dogma. That this was neither true science nor good theology is now becoming clear, boundaries are shifting and the thought of man is moving forward toward the freedom of his birthright. No education which does not arouse some subtler promptings, vague inspirations, — "Thought hardly to be packed into a narrow act, Fancies that break through language and escape" — can rightly interpret the real and deeper sources of human action and progress. Our present emphasis is warped and partial, education should be an epitome of the whole of life, not of a part of it.

The tendencies of our college life, whatever some may say, are neither irreligious nor immoral, but quite the contrary. Religion is a side of the student which the present formal curriculum does not touch directly. To fill out and complete our system, therefore, some broad and effective religious teaching should be provided. Yet just how can such instruction be given in a way to hit the mark and not invade an instinctive sense of individual privilege ? There is no realm of teaching which is more intimately personal and private than that which deals with religious convictions, and nowhere is the likelihood of good and ill result more dishearteningly tangled. Certainly such instruction in college could not be in the slightest degree dogmatic, and any special pleading would as surely defeat the intention. If courses broadly cast could be offered, in which the simple purpose was an impartial and sympathetic enquiry into the highest teachings of the several great religions, with emphasis laid on the ethical and social import of various beliefs, Christian doctrine would inevitably gain in authority and be seen plainly of all men to justify its place in history. It is in a comparative study of religious teachings that I firmly believe Christianity will soonest achieve its rightful and vital supremacy in the minds of college men. Such studies can but add fresh reasons for our faith.

As our colleges give courses in the classics and aesthetics, so they offer ethical courses, and some add a course in the philosophy of religion to their program of studies. Yet for some reason, possibly because the instruction is not simple and concrete enough, possibly the human side is treated too contemptuously, whatever the reason may be, courses in morality and religion are not now fulfilling their purpose because too few students elect them. To make such courses compulsory would be instantly to defeat their high purpose, and yet, somehow, the appeal of the college must be made to transcend the too narrowly intellectual side of man. Aesthetics, ethics, and religion are supremely rich in human interest; surely then courses of increased attractiveness somehow can be fashioned which students will more freely choose to their larger growth and lasting benefit. When this is done, and then only, shall we enlighten the whole man. "His heritage in a deeper life will then no longer be left wholly to time and chance which happeneth to them all."

Before entering upon a discussion of that most interesting and many sided person, the undergraduate, may I in behalf of true science, in which I am deeply interested, add a warning? Scientific studies just now are beset with some of the dangers of an unenlightened popularity. The public has lately taken a wide but too often untutored interest in natural science. A just appreciation of the enormous difficulties which fundamental investigation encounters, is rare, and the limitations of our present methods of analysis are little understood outside the walls of the research laboratory and the mathematician's study. The blazonings of the latest scientific achievements in newspaper and magazine, too frequently immature and incorrect, with emphasis all awry, are building up a quite unreasoning expectation in the minds of credulous readers. The study of science may do for the student other and better things than those he anticipates, yet many will be inevitably disappointed at the problems which the study of science will not solve. Enthusiastic parents, heedless of taste and fitness, too often urge their sons into scientific pursuits, not realizing that lack of intellectual preference in a boy is inadequate proof that he possesses that balanced mind which scientific investigation requires, and unusual pleasure at riding in an electric car is insufficient evidence of a marked capacity for the broader problems of electrical engineering. May not science be spared by some of her too enthusiastic publishers and over credulous admirers, who urge popular and sensational courses in science in place of the fundamental instruction now given. How much longer must newspapers and magazines give money and valuable space for worse than valueless matter only because it masquerades in the garb of science.

Undergraduate Life

From every point of view the undergraduate is the central figure of the college. Clever or dull, industrious or lazy, serious or trifling, he is the only apology the college has to offer for its life. Him our restless critics would give no peace and he takes a gentle vengeance upon his accusers by being unconscious of them. All their thrusts are lost on him, at whose shortcomings they are mainly directed, for the real miscreant rarely reads.

The reformer's indictment is much too long to discuss, here in detail, but he has discovered, for instance, that the average young man in college does not care enough for knowledge to pay proper attention to his studies. But this is not new. the average student never has. Again he finds that too many young men in college drift into a life of ease and indolence. But this is as true out of college as in, and worse, it is a failing by no means confined to the young. To the stress of modern athletics, he claims the average student contributes not his muscle but only a voice. Yet in the earlier days before athletics, which a few of us remember, some men in college were even voiceless. A very slow growth, well rooted in a time-honored past, of indifference to scholarship on the part of some students seems to him a deadly fungus which has sprung up over night, an evil which requires some immediate and drastic remedy if the college is to survive, and he chafes at our tolerance and slowness to act,

An unhappy requisite for any thorough-going dissection is that death must precede it. Thus many a recent thrust at the college is directed at conditions belonging to a past existence. An even greater weakness of the critical faculty, m our day, is in intemperance which loses all sense of proportion and puts things too stronglv — a weakness into which even those in the highest places have sometimes fallen." Thus evils which occur in the few receive a stress and false measure o emphasis which seem to attach them to the many. In the practice of the newer criticism "the exception proves the rule" in an unfamiliar sense.

What class of students in college, it may reasonably be asked, cause us most concern ? Certainly not the capable and energetic men who earnestly seek know edge. Such do not even require very skillful teachers in the pedagogical sense, for given the necessary facilities they teach themselves most things. Some guidance from scholarly men they need, and little else. The dull but hard working student, though less independent, knows quite well how to care for himself and becomes educated in doing so. The real difficulty comes with the indifferent, idle, ambitionless man who often, by reason of native capacity or sound early training easily makes the passing mark which technically puts him beyond the reach o formal discipline and he tempts envious chance no further. This man is no stranger to us, he has always been in college, but we have come recently to take more notice of him. He oftener come of well-to-do parents who also may 100 upon college as a polite formality in a young man's life. But too much emphasis must not be put on money, for the sons of the rich are by no means all idle, nor, alas, are the sons of the poor always industrious. To take an extreme case, he is a man lacking in ideals, or equipped with an unprofitable set. He often comes o college avowedly despising books and their contents. He longs only to study men, to build those life-long friendships which brighten later years, and he too often hearS much to encourage this attitude at home. How then does this youth go about so serious a business as the study of men? By closely observing the more earnest among his teachers and his fellow students who are using their college opportunities to fit themselves for life? No. But rather by seeking companions as passive as himself and drifting in the same sluggish current. I have no wish to give this wretched man more discussion than his flaccid and misguided purposes deserve yet as critics have made much of him and greatly magnified his numbers, surely we should give his weakened state a thorough-going diagnosis that the treatment may be carefully chosen and salutary.

For this class of men home influence, or the lack of it, is more often blame than the college. It is an open question whether the college has any obligation to help a small group of men who care so little to help themselves. In the English system the answer frankly given is that the college has none. The pass and Doll men of Oxford and Cambridge are present examples of a lifeless indifference to earnest scholarship in which the university has acquiesced. In England, however the indifferent are separated from the working students and are never a drag on their betters. In this country the number of this extreme type in most colleges is. as yet, small, but the range between it and the real student is long, and young men who are learning less than they might are scattered all the way between The problem is not new, but it perplexes us and disturbs our counsels exceedingly. It is difficult to conduct a college which shall be at once an effective training school for studious men and an infirmary for the treatment of mental apathy. If it is our duty to the public to "keep such men in college, and many think it is, the problem presented is how to wake them up, and a pertinent question arises — are we at present organized to get at them by the only open door ? Do we often enough get at the center of the man through his false ideals and the husks of his intellectual sloth? Can our teaching be made more direct and personal, not in a meddling way, but by methods vigorous and manly ?

In most colleges this problem has been complicated by numbers. The staff of teachers is not as large as it should be, and the human side of teaching, which requires the closest contact as well as breadth and sanity in the teacher, is in danger. That flint and steel contact between teacher and pupil, which many have reason to remember from the classrooms of their day, is now less frequent. The spark we have seen start mental fires in many an indifferent mind is struck less often. The hope of closer personal attention to students in college is in larger endowments which will sustain a more numerous teaching staff and permit classes to be further subdivided according to scholarly ambition. This is a change which few colleges can now afford to make, for colleges must do with the means they have and keep within their incomes, if they can.

As to how the much discussed decline in scholarship, the real existence of which I seriously doubt, has come about, there are widely different opinions. In the first place, it may justly be questioned whether it is not apparent rather than real. The average student acquires more and wider knowledge in college now than he did thirty years ago. Outspoken scholarly enthusiasm rather than the getting of lessons seems to have suffered. Many students appear to have relaxed a little in the seriousness of purpose with which they approach their work. They certainly show more reserve in the way they speak of it. Here it must be remembered, however, that fashions the country over have changed and the expression of interest and enthusiasm in some subjects is more stintingly measured than a generation ago. If anything we now often get a scant portion in expression where we used to get an over-weight. Nowhere is this change more striking than in the gentle art of public speaking. Yet fashions react on men and our time may have lost something in forcefulness from its often assumed attitude of intellectual weariness, from a painstaking effort at restraint and simplicity of utterance. Our present tendency is to speak on the lighter aspects of even grave matters — possibly a kind of revolt against a flowery sentimentalism, an unctuous cant, or a long face. It is not considered in the best of taste just now to get into heated discussions and controversies over man's most vital intellectual and spiritual concerns.

This habit of repression has come into the college from without. I do not think it began there. Science in the university may have misled the thoughtless to some extent by an emotionless discussion of facts, but facts should be discussed without emotion; it is the lifeless statement of purpose from which we suffer. The driving power of intellect is enthusiasm, and there is no lack of it in that passionate devotion to research which so painstakingly and properly excludes all warmth from its calm statement of results. It is nothing short of a divine zeal, an irresistible force, which urges the true investigator on to those great achievements, which are so profoundly changing the habits of our daily life and thought For any mental indifference, therefore, be it real or assumed, science is in no wise responsible. Science takes herself very seriously and is always in deadly earnest.

In only one phase of college life today may a student, other than shame facedly show a full measure of pleasureable excitement, and that is in athletics. What might not happen to him who threw up his hat and cheered himself hoarse over a theorem of algebra, or over the scholarly achievements of the faculty! Some young men appear to have grown shy and to feel that a show of enthusiasm over ideas reveals either doubtful breeding, a lack of balance, or small experience with the world. They would be like Solomon in saying, "there is no new thing under the sun," and profoundly unlike him in everything else,—an easy apathy to things of the mind and spirit so often passes for poise, and wisdom with the young! Thus some indifference in college and out of it is undoubtedly more assumed than genuine. But again we are in danger of utterance and manner reacting on thought and effort. Signs of such a reaction are already apparent. Thus the college atmosphere has seemingly lost, for the initially weak in character, some of its vigorous and wholesome mental incentive.

May we not henceforth live our college life on a somewhat higher plane, where real simplicity, naturalness, and downright sincerity replace all traces of sophistication and wrong ideals. Let genuine enthusiasm find freer and more fearless expression, that we may become more manly, strong, and free. Why can't some college men stop masquerading in an assumed mental apathy and be spontaneously honest?

Some who have sought an explanation of this slightly altered tone in college life blame intercollegiate athletics for the changed conditions, but I am not able to find the cause there, and believe, as I have already suggested, that it lies far deeper in the changed conditions of society and our national life. The outcry to abolish intercollegiate sports is rather hard to explain. Aside from the assumed injury done to studious habits, apparently no one really objects to sports kept within bounds. But our colleges by agreement may set the bounds wherever they choose. Where, then, is the real reason for complaint? On the other hand intercollegiate sports do more to unite the whole college and give it a sense of solidarity than any other undergraduate activity, and thus serve a worthy purpose. Moreover, the lessons of sport are lessons of life and it is the moral worth rather than the physical benefit of athletics which we can ill afford to lose from student life. They effectively teach a high degree of self control, concentrated attention, prompt and vigorous action, instant and unswerving obedience to orders, and a discipline in accepting without protest a close ruling, even if a wrong one, in the generous belief that he who made it acted in good faith. Sport, like faith, knows no court of appeal. A man's moral fibre comes out in his bearing toward his opponent in the stress of play and in the dignity with which he meets defeat or victory at the end of the struggle. By gallant conduct toward a victorious adversary a bodily defeat becomes a personal triumph. It is only when the spirit is defeated through the body that upright men cry shame! I believe one of the severest tests of a gentleman to be his ability to take victory, or defeat, with equal good will and courtesy toward' those against whom he has bodily contended. Whether we get all that we might out of our college sports is another question, but year by year we approach nearer and nearer to the higher standards of a true sportsmanship.

The problem of athletics suggests another problem which is its twin — What shall we do for the symmetrical bodily development of those who do not train on college teams but who need physical training far more than athletes do ? Here is a question which has not been successfully met and one which demands immediate and wider consideration than it has yet received.

To strengthen interest in scholarship by introducing a larger element of competition than at present is a suggestion which recently has come from several different sources. The competitive idea has long been in full force in the older English universities with what is now regarded there as a result to which good and evil have contributed nearly equal parts. Our own colleges have always offered some prizes for high scholarly attainment but the inspiration for a sufficient extension of the custom to make it a leading idea in our undergraduate life has been drawn from the extraordinary success of athletic contests in arousing student effort and enthusiasm. That a wider competition in scholarship than we now have would produce some useful results lies beyond question, but that those who expect most of all things from it, will be disappointed, may be confidently predicted. It seems to me that the larger part of the ardor students show for athletic contests is due more to the appeal which bodily combat always makes to the dramatic .sense than to the competitive idea in itself. It is the manly struggle more than the victory which men go out to see. I cannot conceive how we are to clothe scholarship contests with a dramatic setting — as well attempt to stage the book of Job, aptly called "the drama of the inner life." The drama of scholarship must ever be a drama of the inner life which will never draw a cheering multitude nor light bonfires. To call men to witness a contest in geometry is less strong in its appeal to human sympathies and interest than the bootless cries of Diogenes prostrated at the roadside, to those who passed on their way to the Olympic games. "Base souls," he cried, "will ye not remain? To see the overthrow and combat of athletes how great a way ye journey to Olympia, and have ye no will to see a combat between a man and a fever?"

Competition is a fundamental law of nature, and it may be a human instinct, but it can never be an ideal, for the virtue of an ideal is a willingness for selfsacrifice of some sort, while the virtue of competition is a willingness to sacrifice others. Competition, therefore, is not a moral force, and as a motive lacks the highest driving power.

Most that I have said of undergraduate life has been in analysis of its weakest members. The vast majority of college men are sound in mind and heart and purpose and no young men were ever worthier of admiration and respect than these. I have not dwelt upon them because their condition suggests no vexed pedagogical nor administrative problems. "They that be whole need not a physician, but they that are sick."

The Teacher

As with the undergraduate, so with the faculty, many a reformer has singled out the weakest member and has seemingly affixed this label to all. But has he forgotten that there are mediocre lawyers, physicians, preachers, engineers, business men, all making a living from their various occupations simply because there are not enough men of first-rate ability to supply the world's needs ? Teaching cannot stand alone, but must share the lot of other- professions. In a gen eration the monetary rewards in most occupations have advanced more rapidly than in teaching, where they never have been adequate, and colleges have felt a relative loss. In law, in engineering, in medicine, in business, the average rewards for corresponding successes are roughly double those in teaching. It is safe to say the colleges are getting far more out of their better teachers than they are paying for. Teaching is to many a very attractive career, not because of the leisure for idleness which it is supposed by some to offer but because of its. possibilities of service to the wholesome life and highest welfare of . society and the State. The teacher who takes his calling seriously and fulfills its high demands spends less time in idleness than his apparently more busy brethren in trade. That he must give many hours to wide-ranging thought and reflection has often misled the public into thinking him an idle dreamer. But dreaming and visions are a part of his business, though the dreamer to be worthy must dream straight-forward and the vision must be clear. How much do we not owe to the dreamer, in science, in literature, in art, in religion, to say nothing of his part in those unthought of benefits, those subtler influences grown up in tradition, influences which have lost or never had a name, which yet continue to inspire and brighten all our days—visions seen by earlier men whose lives must have seemed idle enough to an auctioneer ?

Judged by the higher standards, there are unquestionably a few uncertain and indifferent teachers in our colleges. There always have been. The proportion of men of first-rate ability has improved, but there is need of further improvement. As soon as the public will give the.colleges sufficient means to command the men they want, all cause for criticism will be removed.

We need special knowledge in college teachers, but not specialized men. Whatever the subject, it is the whole man that teaches. While being taught the undergraduate observes the teacher and takes his measure in several well defined directions : — the richness of his knowledge, his enthusiasm for learning, his way of putting things, his sense of humor, and the range of his interests. He shrewdly guesses whether or not his instructor would be an agreeable companion, if all restraints were removed, and the subject of the day's lesson swept out of mind. The student frequently knows, too, whether or not his instructors are producing, scholarly work which competent students elsewhere admire and respect. Nothing gives a teacher more authority and command over the imaginations of his students than a well-earned reputation for fundamental scholarship and research, and nothing so much stimulates the undergraduate's ambition for sound learning and intellectual achievement as sitting at the feet of a master who has travelled the road of discovery. Even as much as a virtuous example breeds virtue in others, so scholarly work breeds scholarship. Presidents and boards of trustees have not always seen the great advantage to a college of retaining a group of strong productive scholars with an instinct for teaching, on its faculty.

All these elements enter into the unconscious respect the student feels for his instructor, and increase or lessen a teacher's influence and worth in the college. The driving of men through college is not as reputable as it used to be, and real intellectual and moral leadership in teaching, is steadily taking its place. Students now largely choose their courses and instructors, for varying reasons to be sure, but some of them are good. Student opinion freed from mixed motive and superficial judgment is usually wholesome and sound.

The college in all its relations is the most human and humanizing influence in all our civilization; and year by year its gains in this direction are substantial. Taking the good with the bad our colleges have never been as well organized and equipped as now, nor have.they ever done their work more effectively than they are doing it today. Any dissatisfaction with college life does not find its basis in comparisons with earlier years, notwithstanding many find, in such comparisons, partial reason for complaint. We are not quite satisfied with the college, because it does not realize our later ideals of education, not because it falls short of our earlier ones. It is well to have ideals and to have them high, and it is a wholesome sign of intellectual vigor to be impatient at the long distance which separates the way things are done from the way we think they ought to be done. Beyond just measure, however, dissatisfaction paralyzes hopefulness and effort; we must keep clear of pessimism, if we are to go forward.

In twenty years of teaching and observation, I have become convinced of some things connected with teaching as a profession. No teacher can hope to inspire and lead young men to a level of aspiration above that on which he himself lives and does his work. Young men may reach higher levels but not by his aid. The man in whose mind truth has become formal and passive ought not to teach. What youth needs to see is knowledge in action, moving forward toward some worthy end. In nobody's mind should it be possible to confuse intellectual with ineffectual. Let it not be said:

"We teach and teach Until like drumming pedagogues we lose The thought that what we teach has higher ends Than being taught and learned."

t ought to be impossible, even in.satire, to say "Those who can, do; those who can't, teach."

The strong teacher must ever have the best of the Priest about him in the fervor of his faith in the healing power of truth. Let our teaching be sane, fearless, and enthusiastic, and let us not, even in moments of despondency, forget the dignity, the opportunity, the power of our calling. The teacher is the foremost servant of society and the State, for he is moulding their future leaders. Sound learning, wisdom, and morality, are the foundation of all order and progress, and these it is the aim of the college to foster. If we can send into the world a yet larger number of strong young men — men clean in body, clean in mind, and large of soul, men as capable of moral as of mental leadership, men with large thoughts beyond selfishness, ideas of leisure beyond idleness, men quick to see the difference between humor and coarseness in a jest, - if we can ever and in increasing numbers send out young men of this sort, we need never fear the question, — "Can a young man afford the four best years of his life to go to college ?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleADDRESS AT THE LAYING OF THE CORNERSTONE OF THE NEW GYMNASIUM

October 1909 By Edwin Julius Bartlett -

Article

ArticleBy vote of the Trustees

October 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1844

October 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1907

October 1909 By Thacher W. Worthen -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

October 1909 -

Class Notes

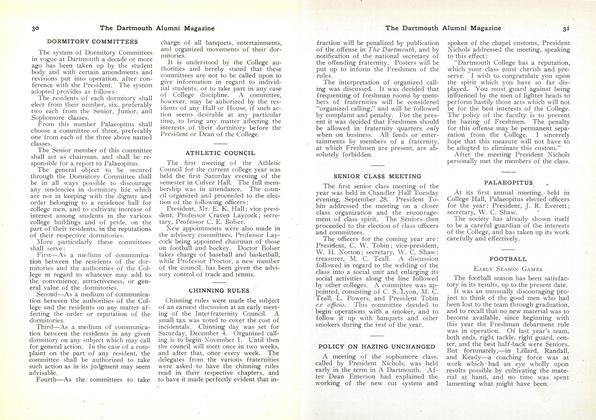

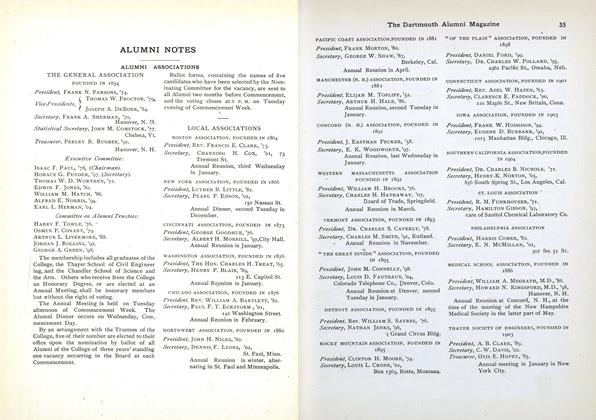

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

October 1909