on November fifth, and the press of the country announced the next morning the distribution which was made of millions of dollars, a considerable portion being bequeathed to colleges and universities. Dartmouth is given one hundred thousand dollars, and the bequest is without trammel of any sort,— the kind of a gift which gives double portion of joy to college administrators and affords opportunity to make the money of maximum service. Before enumerating the long list of institutions to which he gave so generously, Mr. Kennedy wrote these words: "Having been greatly prospered in the business which I carried on for more than thirty years in this, my adopted country, and being desirous of leaving some expression of my sympathy with its religious, charitable, benevolent, and educational institutions, I give * * * the following legacies." One cannot but reflect that a considerable responsibility ought to attach to the colleges and universities to whom Mr. Kennedy's gifts go, not only to train masterful men but also to train to such effect that the colthus use it with recognition of his obligations, welcome of his opportunities, and withal in consummate wisdom.

Meanwhile, the fact is interesting that this, the first considerable gift to the College for some little time, comes from a banker having slight personal knowledge of Dartmouth, and from a resident of the city where the College is less known, perhaps, than in almost any other city of the country. Probably, as in the Fayerweather bequest, the honorable history and current repute are the sources of interest and confidence which have made their appeal to this generous benefactor. And the words of Doctor Tucker, in his report to the alumni, assume new importance:

"The antecedent conditions on which a well-established college may appeal to the larger public are the assurance that its earning capacity has been properly developed, and some clear evidence of the generous support of its alumni."

In addresses, magazine articles, inaugurals, the educators of the country have, of late, been trying to achieve a clear statement of the purpose of the American college. This is well; for if the college can once discover precisely what it is trying to do, it may in time evolve a satisfactory method of doing. And if educators are at last coming to realize that method is of no particular value save as it operates definitely, the world may rejoice as in the face of a new and valuable discovery. Still, clear statements as to the purpose of the college, — or better, clear conceptions of it - can not fully satisfy the inquiring mind. Once that purpose is established, what is to be the test of its accomplishment, and when and how applied ?

The crusty magnate who takes in the ambitious young Bachelor of Arts to be sweeper-out of his office, is often inclined to scoff at higher education as calculated to incapacitate for vigorous and skilful wielding of the dustpan. This is hardly fair. Whatever the estimable features of the dustpan, that instrument is not really qualified to provide an educational test. And, even if it were, the first few months of fledgling A. B.dom provide no true horoscope for the future and imply little concerning the past. College training is, after all, mainly a seed sowing performance whose results can not well be estimated until the fruit has had time to ripen:— a fact lost sight of by those wise critics who, on the basis of its product, contrast the college of a generation since with that of today only to discover the latter a dismal and heartrending failure. As well try to reach a logical conclusion from a comparison of the full blown pippin with the greenest shoot.

Even so, sooner or later, a test is pretty sure to be applied and the college judged,— not by its output of theses, but by its output of men. Power, influence, leadership,— these should properly be found emphasized in the careers of men graduated from an institution that stands pre-eminently for the training of keen and unerring intellects. Yet somehow the world is growing a little wary of power, for it has come to recognize that the robber baron who uses his more active faculties for the fleecing of his fellows, while no doubt politer than his mediaeval prototype of the active bludgeon, is but little more desirable. And the world, too, is losing patience—with influence; too often pronounced "inflooence", and carrying connotations born of dirty politics and venal justice. As for leadership, there is now question as to whither it may point: where the ribbon is, there too often may be heard the clinking handful of silver. The college that trains the mind only may provide the tools of great mischief. From before Abelard until now, mere scholarship has afforded no guarantee of character; and to whatever intellectual gruelling we may subject our aspiring teachers of youth, the truly great educators will always be those who first reach the heart, and after that the head, of young manhood.

The ideals of sport in England and America are discussed in charming and most informing way in the December magazine number of The Outlook, by Mr. H. J. Whigham, who as an Oxford graduate and later as an American newspaper man has had abundant opportunity for comparing the pastimes of the two countries. He takes no stock in the oftrepeated statement that the American amateur is more eager for victory than the English. If possible, the Englishman is the more avaricious, in his opinion, and the logic to the Englishman of losing his place as the first amateur sportsman of the world is so much a calamity that he will not allow himself to believe that he is squarely beaten if any other possible explanation can be invented. In the method, however, of going about the achievement of victory Mr. Whigman finds many differences between the two peoples. Both believe in amateurism, for instance, but the definition is of necessity very different in one country from what it is in the other, for in one country the social system is so unlike that of the other. The emphasis all the while is put upon-the sentiment against specialization in England in contrast to the American method, and he says: "It was Herbert Spencer who, after being thoroughly beaten by a casual acquaintance at billiards, remarked severely: 'A certain skill in the game of billiards argues a well-balanced mind; but such skill as you, sir, have- exhibited, argues a misspent youth'." It is granted that the English attitude is to a considerable extent a pose, and that the idea of unpreparedness is more affected than real, but the writer evidently -feels that so long as even the pose can be kept, English sports will be free from what he conceives to be the deleterious effects of the American seriousness in preparation for games. Mr. Whigham writes in such pleasantly tolerant vein that it is hardly fair to speak of him as making points against our athletics, but in his criticism of specialization he speaks with evident admiration of the ability of the English gentleman to participate in several branches of sport, and his preference to do so, with an evident assumption that few of the American athletes can do this. Whatever the fact in regard to the. athlete at large, this is not a point against the college athlete in America, however, for it is the natural athlete who excels in one game who is generally the mainstay in as many branches of sport as his time will permit him to undertake. The college problem is much more how to keep one group of all-round athletes from too much participation than it is' to find men capable of high-grade accomplishment in all the forms of sport. This very fact, though, substantiates his further criticism that the American system of specialization eliminates all but the fittest who survive the specialization. The writer's criticism of this phase of American athletics is fair, but it is a question how far correction can be made without sacrificing the principle that what is worth doing at all is worth doing well. In his sports more than anywhere else, at the present day, the American youth learns this lesson, and until this is as well taught in some other way sports in their present form, admittedly with many weaknesses, can be spared only at heavy cost.

In like vein with this article Mr. F. Schenck'writes from Oxford to The Nation. At a time when our American game of football is under just criticism for the records of this fall, and at a time when changes must be made, it is vital that we secure the right changes. In earnest desire for the best, some have asked would not a substitute such as Rugby or Soccer be the surest benefit?

In these games, it has been thought, we had a known quantity. But the writer from Oxford disputes this :

"Those who have followed football on both sides of the Atlantic believe it would be a useless retrogression to attempt a modification of American football in the direction of either Rugby or "soccer." It is not the rules that make the English game safe. The excessive softness of the ground, which is covered with very thick turf and rarely freezes or even dries out in the football season, is one explanation of the comparative freedom of English players from injuries more serious than sprains and bruises. But the great reason is the different spirit in which the games are played. * * * * Increase of efficiency at the cost of time and comfort would not appeal to him (an Englishman) at all, for the English athlete has other interests outside his game, and would not think of sacrificing his studies, his social pleasures, or his leisure to a sport.

"It is this calm, casual, excessively amateur spirit, incomprehensible to many American athletes, which makes English games comparatively safe. Rugby, "soccer," and hockey might be dangerous indeed if played "for God, for country, and for Yale." If we wish to obviate the perils of American football it is not the rules we must Anglicize, but the temperament of the players."

The football season has come to a close and as has been the case each fall in recent years Dartmouth has high rank. It makes little difference whether the ranking of one authority or another is taken, or whether we stand relatively to the other colleges in third place or fourth,— the record of excellent accomplishment endures. It was not to be expected that Dartmouth could put the freshman rule into effect and cut herself off from any additions to the not brilliant material of the year previous—mean-while graduating more than half of last year's team—and produce a better team than was produced this year. It was a misfortune that the Princeton game had to be played as an entre'acte set between two scenes of railroad mismanagement actually brilliant in inefficiency. In that game the Dartmouth team was unquestionably outplayed, when is should have won without difficulty under normal conditions, but what-might-have-beens have as little place in football annals as elsewhere, and the result was a tie. The Harvard score is not to be quarrelled with, for Harvard had the stronger team. The results were excellent as they stood, and especially so when all the handicaps

are taken into consideration. If as much is realized in the future in proportion to the resources at hand as has been this year, we shall have greater and greater cause for satisfaction.

William Arnold Shanklin, L.H.D., LL.D., was inaugurated president of Wesleyan University on Friday, November 10. It is interesting to note that Wesleyan is the second New England institution to seek its president from the West; for Doctor Shanklin is by birth a Missourian. His college training was, however, obtained at Hamilton. He began his career as a Methodist minister, serving several pastorates in the West before he was called to the presidency of Upper lowa University. His success as head of that institution led to his appointment to Wesleyan.

In his inaugural address President Shanklin shows himself thoroughly conversant with modern educational thinking. After affirming his belief in the value of the American college, despite the attacks which are being made upon it, he declares its purpose to be training for service. To this end the faculty is of chief importance, above all a faculty of teachers; for in the university "the function of teaching is necessarily subordinated to investigation." Hence President Shanklin inclines to favor the small college which enables the personal touch between professor and student. He further congratulates Wesleyan upon having avoided the wiles of the elective system already discredited and ejected from the house where it was born. Yet the faculty and the curriculum exist of necessity for the undergraduates. Those of Wesleyan present much the same types and much the same problems as those of other institutions. President Shanklin would eliminate the loafers; but he expresses optimism with regard to the others. Student self-government he considers essential, and finds satisfaction in the large measure of its success at Wesleyan. He comments favorably, too, upon the usually sane vision which students display in choosing the leaders of their activities. As for athletics, while he admits the possibilities of evil in them he unhesitatingly declares his belief in their ultimate benefit. His conclusion amplifies the thought that "the education that forgets God omits its major premise"; for "to the college which maintains that 'the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom' the nation must look for its leaders."

A prophet is quite likely to remain without honor in his own country until sudden and unexpected events bring him into illuminating contrast with a vaunted rival from over the border to the revealing of local virtues hitherto unaccounted. Those Dartmouth folk who a few weeks since, by virtue of the complete paralysis of a transcontinental railway were trailed through all the side aisles of Jersey's classic suburbs returned to Hanover to find welling up within their breasts mingled feelings of affection and respect for the hitherto often anathematized Boston and Maine. Delay, disappointment, and distress frequently provide opportunity for reflection, and of reflection thoughts are sometimes born. Come to think of it, in the light of experience, the Boston and Maine treats us very well. To be sure it does not run trains from Boston to Hanover at five minute intervals, its locomotives are not always free from asthmatic disturbances, and in winter are sometimes subject to chills. Nor do the architectural details and public conveniences of the Norwich-Hanover "depot" vie successfully with those, say, of the Pennsylvania Station in New York. Nevertheless the Boston and Maine gives this community all that the community pays for and probably a little more. Our demands upon it are variable and uncertain, but they are, at nearly all times, met with courtesy and promptitude. Indeed, it is doubtful whether any place of size and situation similar to those of Hanover can boast of better rail and mail accommodations than we enjoy. But whatever else may be said, one fact stands beyond dispute or peradventure: the Boston and Maine never forced a Dartmouth football team to resolve itself successively into cross-country club and starvation squad on the eve of an important contest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

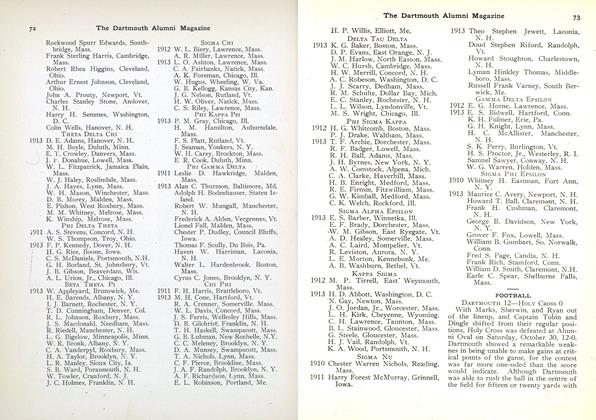

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1909 -

Article

ArticleSHALL OUR COLLEGES BE REORGANIZED ?

November 1909 By Ashley Kingsley Hardy -

Article

ArticleAN EDUCATIONAL TRACT ON THE PH.D.

November 1909 By E.M.H. -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY ELECTIONS

November 1909 -

Article

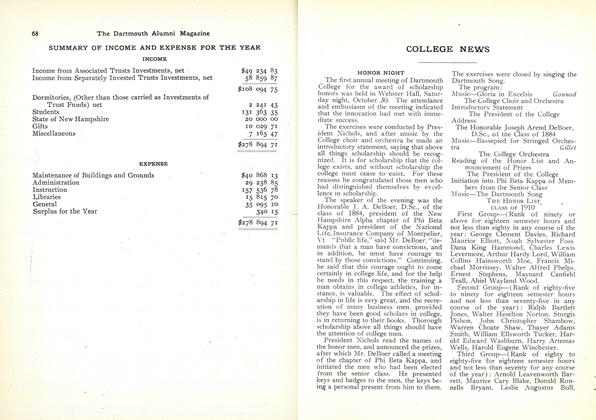

ArticleHONOR NIGHT

November 1909 -

Class Notes

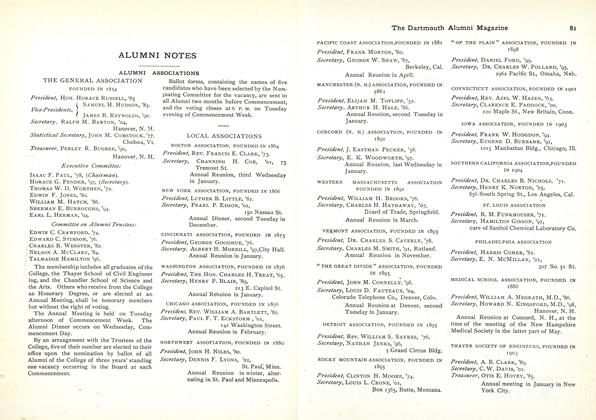

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

November 1909

Article

-

Article

ArticleSOME INTERESTING GIFTS

November, 1915 -

Article

ArticleA Banner Year for the D. O. C.

October 1937 -

Article

ArticleExtra Payments Made

January 1949 -

Article

ArticleMaking dormitories "more than just places to crash"

June • 1985 -

Article

ArticleCLUB HOUSE REMODELED

February 1940 By Edward Fritz '40 -

Article

ArticleTrials, Tribulations, Success

March 1942 By RALPH SANBORN '17