The man must be bold, and presumably bad, who commits the sacrilege of entering into the temple of higher learning and touching with profane hands that fetish of modern education, Ph. D.ism. He must come in no impersonal way, lest his associates suffer for his impiousness. If his dwelling be in the classic precincts in which a college administration holds sway, in justice he must declare his detachment from it in his irreverence, that it be not defamed. And further he may be sure, whatever his beliefs and protestation thereof, that in not worshipping this image of knowledge he will be considered to be without reverence for the knowledge which it assumes to represent.

Nevertheless it is not failure to recognize the need 'of at least three years of advanced work that causes now and then one to declare that the training for a doctorate of philosophy is not a training of maximum efficiency for college teaching; and it is not lack of conviction that advanced work would be best done underthe expert guidance of those who have explored the realms of knowledge that causes doubt as to the efficacy of the Ph.D. training to lead prospective teachers along the highways of learning, except the road be very narrow and very straight. The lamp of learning presumably radiates light and illumines all about itself, but the tendency at most universities is for the doctorate of philosophy to become a bull's-eye lantern, searching out by its straight and garish rays the minutest objects which lie before it, but leaving all else in a deepened darkness.

After all, the American college cannot spare the type of the old-time teacher without undesirable change, and the loss of one of these in the present day occasions expressions of deep regret far beyond his local field. The New York Sun says editorially of Professor Packard's recent death, for instance, after reciting his honorable service at Dartmouth and Princeton:

"As translator, editor, and historian, as memorialist of Princeton's great men of the past, as essayist and reviewer, Professor Packard was known to his contemporaries. As scholarship progresses and new knowledge replaces old theories, this work passes with its day ; but the routine work of the classroom endures longer in the lives of the pupils, and passing from one to another partakes of the nature of immortality. Professor Packard not only knew and loved the classics, but knew how to make others love them; and the memory of his personality, full of the charm of ripest acquaintance with the poets and philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome, is a better monument than boisterous renown won in wider fields of activity."

New ways are not old ways, and modern needs are different from those of past decades, but the increase of intellectual acumen in modern training ought not to be so often accompanied by atrophy of the bowels of compassion.

Those skeptics who are also optimists believe that in the fullness of time either the requirements for the doctor's degree will be fundamentally broadened, or that a new degree will be devised requiring a like amount of work but of different scope. Indeed the former is even now the case in some'departments in some of the best American universities, and colleges seeking teachers are so much the gainers.

"The Making of a Professor" by Grant Showerman in The AtlanticMonthly for November is a novel tractdealing with this subject in considerable detail. The Professor, by his dissertation on Sundry Suffixes in S, had five years before earned his Ph.D. Since, he had been hard at work on Terminations in T, and he projected another volume on Prefixes in P in the Plays of Plautus. But now something was amiss.

"The fact is that the Professor had for some time been wavering in his faith. Not his religious faith,— I don't mean that, for Consonantal Terminations had so far crowded that out that it claimed small share in the Professor's cogitations, —but his faith in the importance of terminations in general, and particularly of Consonantal Terminations in the Comedies of Terence. He had been losing indeed he had lost—the reposeful sense of equilibrium and stability which had been to him the peace that passeth understanding so long as he had entertained absolutely no question as to the claim of Terminations to be his mission in life. And now a crisis was at hand.

"For you must know that the Professor was, or had been when he came home from Europe to occupy his chair, a strictly approved product of the Great Graduate System of Scholarship. The appreciation of that fact, and of the process of its, achievement, will help you to understand his present frame of mind."

He had been an eager student of classics in the secondary school, and his enthusiasm had grown during his college course. In' enthusiasm for literature, and desire to lead others to the fountain of whose waters he had drunk so satisfyingly he determined to teach. "He must be a scholar sans peur et sans reproche, and to insure against the possible failure of the world to recognize his genuineness, he must be approved by the System, and be stamped Ph.D.; and because the value of the stamp depended very much upon the imprimeur, he must go to a university which enjoyed an unassailable reputation for Scholarship."

At first he was not pleased with his training. "He had expected to continue the study of the Latin Classics,— to read, interpret, criticise, and enjoy; but what he was actually occupied with was a variety of things no one of which was essential to literary enjoyment or appreciation, and whose sum total might almost as well have been called mathematics, or statistics, as classical literature. When he thought of his college instruction, he wondered whether the end and the means had not in some way got interchanged. He felt that now he was dealing with the husk instead of the kernel, with the penumbra rather than the nucleus, with the roots and branches, and not with the flower. In his gloomier moments, he suspected that his preceptors and companions were actually ignorant that there was a flower; if they were aware of it, they were at least strangely indifferent to its color and perfume. * * * * * He found himself thinking of five-legged calves, two-headed babies, and other sideshow curiosities. But he had always been docile, and did not fail to reflect that scholars of reputation surely knew better than he what stuff scholarship was made of. He put aside his own inclinations, and dutifully submitted to the System; its products were to be found in prominent positions throughout the land, "and what better proof of its righteousness than that?"

But he soon learned his lesson and looked with pity on his former sentiments. "It was a trifle tedious at times, and he found himself wondering what there was about learning that it should be so stupid. He was the least bit surprised to find that it seemed expected that he would wonder; for it was explained to him more than once that it was all for the best, and he would soon get used to it. Every fragment of truth was important, he was told, and the slightest contribution to knowledge a legacy of inestimable value, whatever its apparent insignificance; and besides, this was the way it was done in Germany. He soon learned that the appeal to Germany was considered final, and even made use of it himself when it came handy."

In time he became a prize product of the System and fame preceded him home. His dissertation was published, and the reviewers praised his method, his thoroughness, and his accuracy. That the intrinsic value of his work was not mentioned troubled him not at all. When his beloved Alma Mater called him to herself he tasted all the joys of success, and returned to enter upon his life-work. "The Professor felt keenly the responsibility of his position. As he remembered it, the atmosphere of his Alma Mater had not been scholarly. * * * * * The institution and the department needed a standard-bearer of Scholarship. So the Professor had raised the standard and begun his march. He set out to cultivate the scientific temper among his students and to set an example to his colleagues. His accuracy was wonderful, his conciseness a marvel, his deliberation unfailing, his thoroughness halted before no obstacle, his method was faultless. His recitations were grave and serious in manner and content. He never Stooped to humor, for Scholarship was a jealous goddess. * * * * * Being really sympathetic and sensitive, the Professor noticed more and more the glances of his students. Once he detected two of them simultaneously touching their foreheads, and passing a significant wink. This came as a shock, and set him vigorously to thinking. It began to suggest itself to him increasingly that what was so fascinating to him might not be even mildly interesting to younger people who had not enjoyed his advantages of study and association."

Following a summer of doubt he returned to his work, but with less confidence than heretofore in his method, and in those things learned from the System. With himself he had frequent debate, and his other self, as Mr. Homo, said to him, "To be able to commune with the souls of the world's great poets,— who are, after all, the world's greatest creative scholars,;— and to interpret their message to humanity, is a higher form of scholarship than the capacity for collection and arrangement of data about them. That is the work of a mechanician, and requires ingenuity rather than intellect. It doesn't really take brains to do that. Remember that you are a teacher of literature, and that the very highest form of creative scholarship in literature is to produce new combinations in thought and language, just as in chemistry it is to discover new combinations of chemicals. If you cannot create, the next best is to interpret and transmit," and the Professor accepted the thought. "His conviction and conversion were only the natural result of a long process. The trammels of the System should no longer be on him. Nature, the good friend whom the pitchfork of the System had expelled, should henceforth be allowed a voice in the direction of his effort. He would know more of great books, of men, of life; his tongue and pen should flow from inspiration as well as industry; he would tell not only what was, but what it meant."

The end of this morality play of education is that the Professor, glowing with pleasure at the promise of the future, surrounds himself with the works, long neglected, of his favorite poets, novelists, historians, and essayists, and looks forward to teaching, gratifying to himself and profitable to his students.

If the writer had been speaking of the college instead of the teacher, perhaps he would have said that the institution was fortunate in that the Professor regained his perspective so quickly. To the layman, certainly, the fact that so many men of high worth emerge from the training with disposition and sense to utilize its benefits and to be uninfluenced by its defects makes for great respect for the individuals of college faculties rather than for esteem for the methods of graduate school curriculums.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1909 -

Article

ArticleThe will of John Stewart Kennedy of New York was filed on November

November 1909 -

Article

ArticleSHALL OUR COLLEGES BE REORGANIZED ?

November 1909 By Ashley Kingsley Hardy -

Article

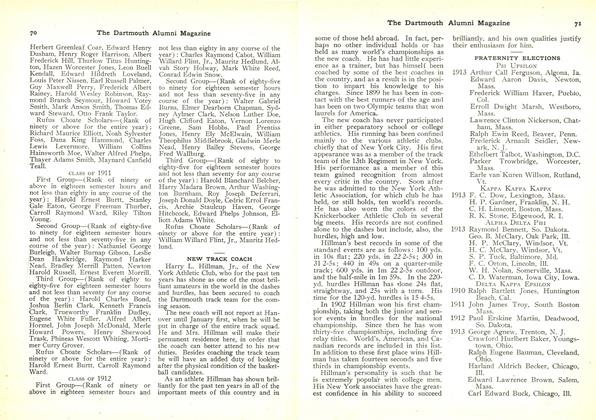

ArticleFRATERNITY ELECTIONS

November 1909 -

Article

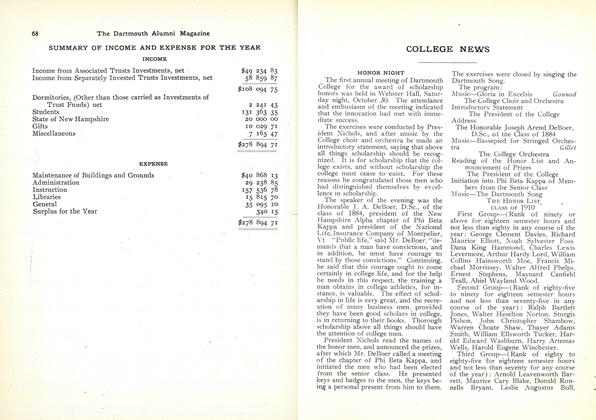

ArticleHONOR NIGHT

November 1909 -

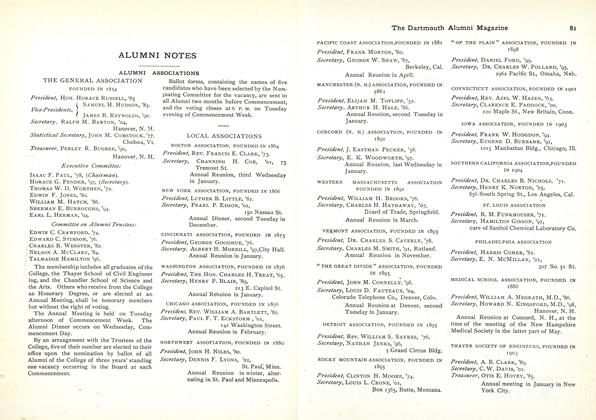

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

November 1909