The current discussion of ways and means to improve American colleges has aroused a more widely-spread interest in their internal problems than has ever existed before. Perhaps the most important study of college questions by one not professionally connected with higher education has been made by - Mr. Clarence F. Birdseye, a graduate of Amherst and successful lawyer in New York, in his two books "Individual Training in our Colleges,'' and "The Reorganization of our Colleges."

In his earlier book Mr. Birdseye attempted "to show the history, content, and purposes of our older colleges, and the evils and shortcomings of our present institutions and their lack of system and foresight—all from the standpoint of the undergraduate." In "The Reorganization of our Colleges" (New York: The Baker and Taylor Co., 1909. pp. IX+ 410) Mr. Birdseye advocates the introduction of modern corporate business methods into the administration of the college as the only means of removing present evils and assuring proper educational efficiency.

Mr. Birdseye divides all college activities' into "six great departments or classes: (a) finances, (b) instruction or pedagogy, (c) administration, (d) the executive, (e) the trustees or board of control under whatever name, and (f) the student life, or that portion (about ninety per cent) of the undergraduates' time not spent in recitations, lectures, or other personal contact with their instructors. The student life must be further subdivided into the college community life and the college home or family life."

The student life and administrative departments are the ones primarily involved in the scheme of reorganization, though instruction is indirectly affected to a large extent.

Part II of the book is devoted to a consideration of the importance of student life, which Mr. Birdseye finds has been uniformly and culpably neglected by college authorities. The point is first made that the college is no longer a school based upon the home, but a quasi public corporation, most nearly akin to a municipality, in which the students bear a threefold relationship like citizens in a community, (a) to the college authorities, (b) to each other in the college community life, (c) to their intimates in their college homes. The two last named relations comprise the student life department and occupy ninety per cent of the student's time. It is here and not in the ten per cent of the student's time spent in classroom, that character is chiefly formed and the future citizen prepared to play his part well or ill in the community and the home. The college ought, therefore, to study this department, obviate its evils, and use its. good influences as a positive educational force of great value. The importance of student self-government in producing good citizenship is urged, and reference made to the systems in use at Columbia and Amherst.

Physical education and training are rightly assigned a high position, but "we must not overlook the fact that college athletics are primarily for relaxation, recreation, and health, and hence, indirectly, for better intellectual work in college and for greater efficiency in after life. We are too apt to think that they are for the honor and advertising of Alma Mater."

The significance of the student's college home lies in the fact that "it largely determines, possibly throughout life, the purity or impurity of his thoughts, habits, and language; his personal power over his fellowmen, or, in college phrase, his ability as a 'mixer'; his intellectual and moral attainments; and his readiness to receive and assimilate religious impressions. In other words, it affects, in every plane, his life as a citizen in college and in after years." The policy of providing no dormitories, followed by most state universities, which forces the students to live in private houses, is justly condemned. The neglect of the colleges to furnish suitable homes has been met by the fraternities. Mr. Birdseye is an enthusiastic advocate of the fraternity house which affords living and boarding accommodations, as being the best type of college home. He calls upon the alumni to take steps to make and keep these college homes clean and uplifting, and instances one fraternity which employs a traveling secretary with excellent results. Dormitories Mr. Birdseye refers to, somewhat unjustly it would seem, as "barracks." While modern dormitories probably offer more comfortable quarters than the average young alumnus will find awaiting him at once in the cold world outside, it must be admitted that they lack a nucleus around which home-like associations and definitely elevating influences may gather, and therefore are by no means ideal college homes, For non-fraternity men Mr. Birdseye would have the colleges provide homes modelled on the chapter houses. We hardly think Mr. Birdseye has spoken the last word in this question, which has not been settled satisfactorily anywhere, and, through having been neglected so long, must probably be met by different colleges according to local conditions. The ultra-luxurious fraternity houses found at some institutions certainly complicate the problem rather than help to solve it.

The plain-spoken chapter on "College Homes and College Vices" treats one of the most difficult matters with which college authorities have to deal, and yet one in which their responsibility to the state and the home is of the greatest.

Summing up his study of what he calls the student life department, Mr. Birds-eye finds that colleges may be classified in three groups according to the dominant influences in each. There is "one class of colleges or college forces which places an undue emphasis upon what they are pleased to call scholarship, but what may too often be merely rank, and a diploma under a vicious marking system." Most commendable is the statement : "I would gladly double the amount of solid intellectual work done by the average student, but at the same time I would make it perfectly plain to him that I was not aiming to raise his college rank but his future effectiveness— and the average student would respond most heartily."

But the difficulty is that the average student doesn't respond heartily, because he considers the instructor is aiming at something too indefinite. Hence the demand in many quarters for a more vocational form of college with courses definitely adapted to the future career of the student.

Another class of colleges has placed undue emphasis upon the college community life, chiefly as seen in intercollegiate athletics, with results which have been disastrous in many ways.

A third class has unduly developed one side of the college home life, as seen in the fraternity and the club.

If we study the college carefully, however, "we shall then perceive that the trouble has not been with those new elements of the college, but rather with the way in which these elements have been handled; that electives, and Germanization, and the new college-university, and intercollegiate athletics, and the fraternities, and scores of other things, are essentially right and necessary in the new college state—although they were not in the older college based upon the home—and that the trouble has been that, in all these cases, we have allowed the means to become the end, the servant to become the master; and then the pedagogical department has suffered accordingly."

The one thing needful to weld these various and often conflicting activities into a force for the prpduction of a high type of citizen, is according to Mr. Birdseye; the reorganization of the college by the introduction of a separate administrative department such as is found in a modern business corporation. This department would be coordinate with the department of instruction, independent of it, and responsible to the executive, thus leaving the faculty free from general administrative burdens. The remainder of the book is given to an exhaustive exposition of the need, place, and probable effect of this new department. Administration, Mr. Birdseye explains, has now become a science in itself and may be applied to any form of commercial or manufacturing enterprise. Colleges have not taken advantage of this science, because "they mistake questions which are administrative in their nature for pedogogical questions, and then imagine that if new problems of administration arise within their walls, their pedagogical experts must master and solve these questions." The college is as it were a factory in which a corps of instructors is engaged in producing intellectually trained men for future citizenship. The primary unit of the reorganized college should be the capacity of its "plant," that is to say of its teaching force, taken in connection with its material equipment. Under this system each instructor would be considered "(a) principally and primarily as to the amount of time which he must have to himself to conserve and develop to the utmost, and keep in repair and highest working order, his intellectual and teaching powers; (b) how much time in addition he can, to the greatest advantage, spend upon teaching; and (c) how many students he can teach most efficiently within the time allotted to teaching." At present colleges overload their machinery: "Every year we turn out a fine crop of prospective college instructors of great promise and with high ambitions and gifts. They feel capable of doing good original work and of bettering the methods of the average professor under whose instruction they have sat. But thirty years before, that average professor had had the same capability and ambitions, until these were killed out of him by the poor administrative methods and bad factory practice of our colleges." At present there is much jealousy in colleges in regard to administrative reforms, because they are not under the charge of a separate and coordinate department of administrative experts, but under pedagogical colleagues who are deputed to do some extra and muchneeded administrative work."

The duties of the new department are shown by Mr. Birdseye's tentative division of it into bureaus: (1) Bureau of statistics and.forms. A much larger use is to be made than at present of blanks, and statistics of various kinds are to be collected and made available. (2) "The second bureau will be that of the college waste heap. Its duty will be carefully to examine and rectify the educational of other factors which, before, during, and after a student's course, tend to produce bad work or prevent good work." (3) "A third bureau must be that of college activities, which will study and be responsible for the college community life and the general student atmosphere." This bureau works with (4) "That of the college home life, which must have charge in a large yet intimate way of the college homes and their highest inter- ests." Other bureaus are those (5) of health and physical exercise; (6) that of the graduate field, which will aid alumni and prepare students for outside conditions; and (7) that of the college plant, which "will have a general oversight over the work of the teaching staff."

It will be noted that a number of these bureaus are already present in some form or other in all large institutions. What is really new in Mr. Birdseye's plan then is, first, the addition of new bureaus whose duty it is mainly to study and oversee student life and the relation between instruction and students outside the classroom; and second, the union of these and other bureaus into an administrative department, with a new college official at its head. There is certainly need of sympathetic investigation and wide control along the lines of the new bureaus proposed, though it is by no means clear just what or how much they could accomplish. The subject could at least be illuminated by the methods of modern social study and certain facts perhaps established, e.g. as to the influence of fraternities or intercollegiate athletics, where now we have really only personal opinion. This seems, however, a field for the trained student of social conditions rather than the administrative expert, for the problems involved are not business ones. There is no more need of factory superintendents here than of factory operatives in the instruction corps.

It would probably be to the advantage of all concerned to relieve the faculty so far as possible of general administrative duties, and this could perhaps be best accomplished by the establishment of a separate department.

We do not think it would prove a panacea for all college ills, or be able to perform all the functions Mr. Birdseye expects it to, for it is not so easy to draw the line between instructional and administrative questions as he assumes it is. The most important problems before the colleges, aside from student life perhaps, which is primarily social, involve both elements inseparably, and will, therefore, be best solved by men equally familiar with both.

One does not have to agree, however, with all Mr. Birdseye's conclusions to give his work high credit as a sincere, and it is to be hoped, fruitful contribution to the study of higher education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

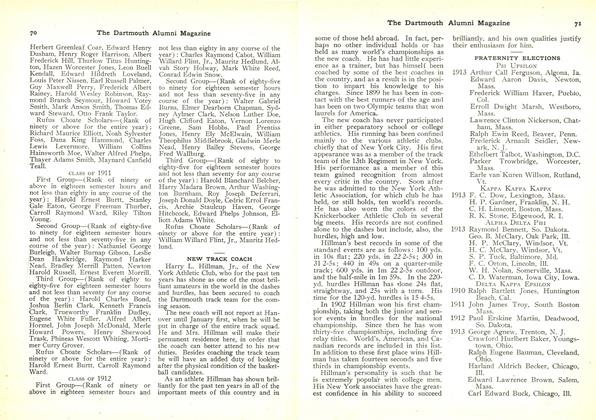

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1909 -

Article

ArticleThe will of John Stewart Kennedy of New York was filed on November

November 1909 -

Article

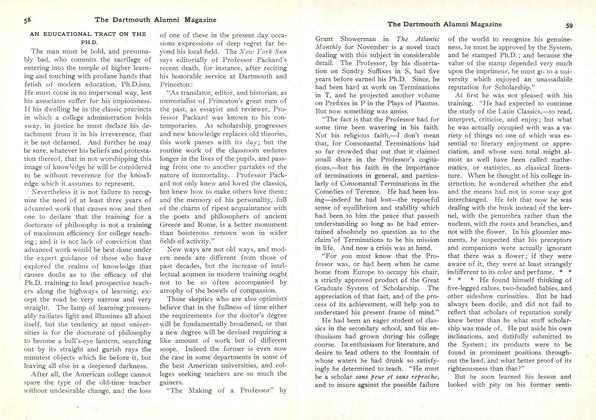

ArticleAN EDUCATIONAL TRACT ON THE PH.D.

November 1909 By E.M.H. -

Article

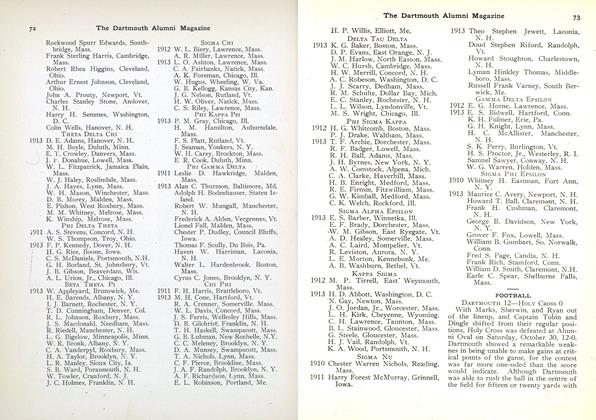

ArticleFRATERNITY ELECTIONS

November 1909 -

Article

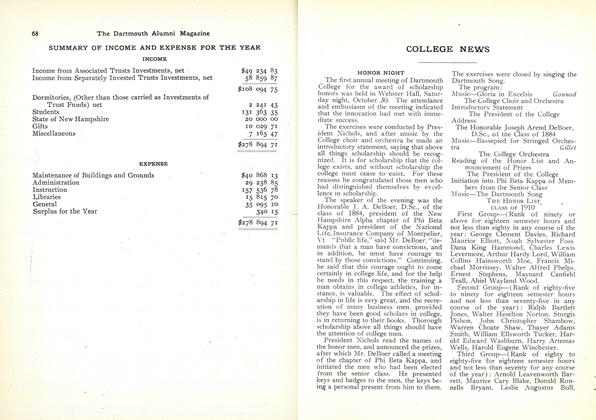

ArticleHONOR NIGHT

November 1909 -

Class Notes

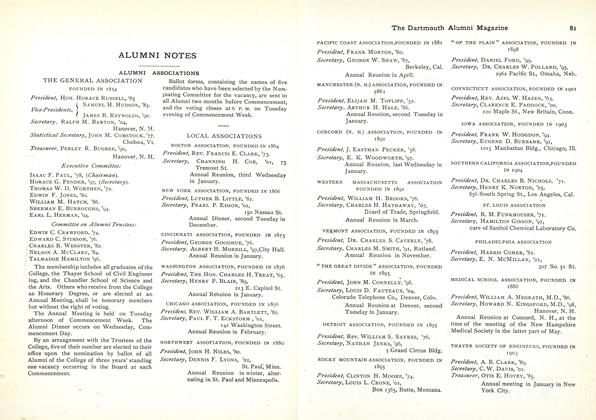

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

November 1909