during the holiday season has read of meetings here, there, and almost everywhere, of learned societies and associations. If one has had anything of curiosity concerning the subject, he has discovered doubtless that the membership lists of these were really rolls of college teachers from the different institutions of higher learning throughout the land. The gatherings have drawn men alike from McGill and the University of Texas, from Bowdoin and the University of California. Wherever there are colleges and universities, thence have representatives gone to meetings for the discussion of their subjects and for the meeting of men of their kinds. It is probably not far from the truth, moreover, to say that to those colleges which have been proportionately the better represented in these gatherings will come in subsequent months the greater inspiration in the class-rooms. It is becoming increasingly recognized that no teacher can inculcate enthusiasm to a degree beyond that which he has himself,— some student may go on to a higher level, but not through the leadership of the man who accepts the mission of leading him. It becomes every teacher's duty to himself, therefore, to keep his inspiration strong and his ideals clear-cut, for only thus can his individual advantage be conserved. Likewise it becomes the responsibility of each college to afford every opportunity within reason for its teachers to have access to the springs whence enthusiasm is derived. It is in this conviction that provision has been made at Dartmouth for supplementing to an extent the resources of faculty members to. attend these meetings, and it is likewise in this conviction that satisfaction comes in finding the College so largely represented on the various attendance rolls. The tonic effects in meeting with one's fellows in zest for given work is not to be lightly regarded, and excellent as are the papers and discussions of any group of meetings, the benefit lies not more in these than in the mingling of men seeking the same ends, meeting similar difficulties, and striving alike for methods of overcoming or neutralizing them.

Another thing which such assemblages are accomplishing is making college teachers known to the outside public as they are, rather than as they have been conceived to be. While one Boston paper speaks of an individual of a small group of men as attired with a "dress tie under one ear as befits a professor," there has been expressed rather widely in the papers a somewhat surprised opinion that after all these college men are as other men are. Not only in outward dress but in less superficial ways they are not to be distinguished from the citizens of ability in other walks of life. It is perhaps true that there has been some change in the outward appearance of college teachers, and it is possible that a period of comparative stagnation in institutional development bred sartorial and mental affectations which no longer are bred. But the fundamental fact is that the colleges are now accepted as a constituent part of the national life, and not things apart from it. About the only access to the professions is through the schools of higher learning, and each year an increasing number of business men is recruited from the same source. College ' men are more and more prominent in the major government offices, and from the various faculties department experts are being chosen for government work. Mutual appreciation between the colleges and the outside life is greater than ever before in this country, and in this status the position of the college teacher acquires even added dignity and importance. From time to time we read, as in the New York Times of last year: "There have been and are many noble teachers, while about the importance of teaching in every sense there can be no question.

"Nevertheless, one cannot help remembering that between the ideal teacher and the majority, the very large majority of teachers, there is an easily measurable difference, and reflection upon the characteristic habits of teachers as a class is calculated to inspire dubiety whether teaching has upon its exponents an effect as ennobling and enlarging as would reasonably be expected if all the praises it has received were true. As a matter of fact, the world has always looked more than a bit askance at its schoolmasters has been more than a little dis- posed to smile at their peculiarities—has never manifested what could fairly be called a strong inclination to seek advice from them in emergencies or on the practicalities of life."

But under the influence of modern tendencies, though we have to grant at present much truth to such a statement, still we believe more and more surely that the words of President Angell to the Association of American Universities will be accepted by the public at large, "Teaching is the noblest of professions; I believe it leads all other works."

The "chinning season," which came to a close early in December, appears to have been productive of much dissatisfaction among the fraternities. However apparently well guarded by rule and agreement against premature influence, the guileless Freshman nevertheless seems to fall victim to illegitimate devices. If current reports are to be trusted, it is evident that the fraternities of the College have formed the unfortunate habit of pledging themselves to one line of conduct while secretly operating upon a quite different one. This is not as it should be. If college men can not deal honorably one with another, then higher education presents some faults not generally recognized, perhaps, by the educational reformers, but far more dangerous than those which critical individuals are wont to decry. A lack of intellectual acquisitiveness may be tolerated where underhand dealing may not. There has been some talk of meeting the situation either by holding the "chinning season" at the very opening of the college year, or by postponing it until late in the second semester. Each of these devices has been tested in the past, and each has been found unsatisfactory. In theory, the present system is very nearly perfect. The lack of a proper attitude on the part of the men concerned is all that prevents its proving perfect in practice. For some, however, it is always necessary to be assured that it pays to be good, and that to be bad brings disaster. For influencing such as these, the existent court of last resort, the interfraternity council, which is not certain to be free from offenders, is a source of weakness rather than of strength. If there could be chosen a thoroughly impartial body with power to investigate alleged violations of the rules and to punish violators of them, much would be done toward allaying the mutual suspicion and distrust which are largely responsible for the present deplorable situation. Yet the system which will be entirely satisfactory to all the fraternities will, of necessity, never be evolved. Those which from time to time secure the delegations that they want will be pleased; those which are disappointed will naturally complain. In any event, there is one custom which the spirit of self-protection should cause the fraternity to root out: that is the habit of a few world-wise Freshmen in each entering class of banding together into a group of callow homogeneity with a view to forcing some fraternity to take all or none. The process of "chinning" as now sanctioned carries with it sufficient humiliation for the upperclassmen without this added touch of the ridiculous.

The changes being wrought by the new administration at Harvard are the subject of no small amount of favorable notice from the press. Especially upon the sudden turning away from an unrestricted elective system has attention been centered. Yet Harvard's move in this matter, if viewed in the light of general educational tendencies, is less revolutionary than the casual newspaper reader might suppose. Whatever local peculiarities the system now in process of adoption may exhibit, in its essence it is the "group system," which has for some years been in successful operation at Princeton, Yale, Dartmouth, and many another institution. Harvard's eventual conversion to the idea that has elsewhere been so stoutly maintained in the face of considerable pressure will be none the less welcome, no matter to whom the dis covery of the idea is credited.

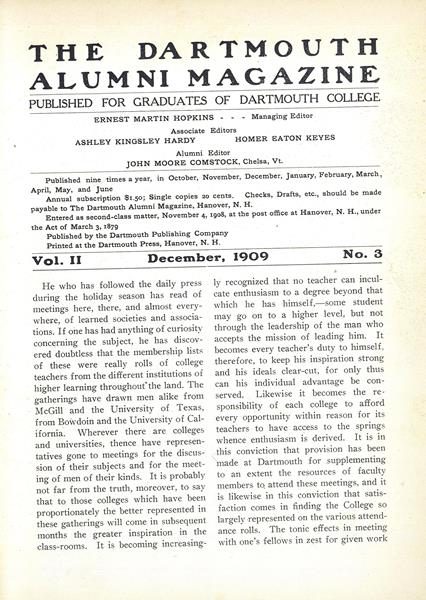

That the new administrations of other colleges should have obtained less publicity than that of Harvard does not necessarily imply less activity on their part. Harvard, in choosing her President, chose a member of her own faculty, a man well acquainted with existing conditions and with a policy definitely formed on the basis of intimate knowledge. To him, further, was open an opportunity not open to others unless, perchance, they were minded to champion that which he was last to cast aside. In the case of Dartmouth, indeed, it may be doubted whether any violent change in administrative policy would have been well received by the alumni or by the friends of the College. To those who have followed the work of President Tucker it has long been obvious that whatever changes his successor might make must be those of gradual evolution through things already established, rather than revolution through disestablishment. And such changes are wrought neither rapidly nor with opportunity for display. Hence the attitude of President Nichols has been one most gratifying to all concerned.

With a secure sense of peace and well being, the College is going about its appointed tasks! Meanwhile the President is devoting himself to mastering the individuality of Dartmouth. Until that is accomplished we need hardly expect definite public pronouncements. This, however, does not mean that President Nich ols is doomed to silence. Since his inauguration he has made frequent addresses before a large variety of audiences, and in every instance has carried a convio tion of sane judgment, clear purpose, and lofty idealism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Article

-

Article

ArticleHelp

September 1979 -

Article

ArticleAROUND THE GREEN

Sept/Oct 2006 -

Article

ArticleVISITING VOICES

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 -

Article

ArticleUniversal Military Training

March 1952 By BRIGADIER GENERAL HARRY H. SEMMES '13 -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Takes To Water A Revival of Crew & Aquatic Sports is Under Way

May 1934 By Phil Sherman '28