by the faculty,looking toward doing away with the injuries to scholarship which came from the attempt on the part of many men to carry more than a just burden, of work, under the influence either of past failure or the desire to discount future weakness. It appeared indisputably that men failed to exert needed .effort to make passing grade even, secure in the optimism which allowed them to trust in the opportunity to load upon themselves, in the future, extra hours to compensate for courses failed. Likewise it was shown beyond cavil that men of indifferent scholarship, in the effort to make up failures past, crippled themselves by the election of extra hours, and in the end failed more. In like position also were those who elected beyond their capacity to do good work, in order to guard against future failure. The Registrar has worked out the results of the election of extra hours. Freshmen have not in the past been allowed to take extra hours, except in very unusual cases, and under the new rules Seniors will be allowed to a certain point, to elect extra hours, if needed for degrees ; the classes to consider, therefore, are the Juniors and Sophomores. Figures from a semester last year, typical of any semester, are as follows : 178 were granted permission to elect additional hours ; of the 178, 124 failed to make the extra courses, 58 withdrawing and 66 failing ; of the 66 who failed, 33 failed in hours beyond the number of extra hours elected. There is little of gain and much of disadvantage, therefore, to the very men who elected the greater number of hours. But the vital injury was to the more than 900 men whose courses were weakened by the incubus of men without ability or serious purpose to keep the pace. Rules were therefore passed, after careful investigation, requiring evidence of at least medium ability before any man should be allowed to elect hours beyond the point at which he had before failed. These regulations have not been understood, either by alumni or by undergraduates, but their purpose is to benefit the College and the individual student. The theory urged by some is all right—that the College must not let the individual student suffer — but in a question between the privileges to be extended to the fag-end of the College, something over a hundred flunkers, and the rights of the rest of the students, nearly a thousand men, there can be no question, even if the regulations fall heavy upon the man who fails. But in these rules the real interests of the backward men also are conserved, as consultation of the records will show.

At a meeting of the faculty, held March 29, a vote was passed which is really complementary to the regulations referred to before. The system of college honors, in effect since 1895, was done away with, and substitution was made of one arranged with the intention of making the widest possible appeal through the stimulus of recognition of excellence in general or special scholarship. The new honor system has grown out of a careful study of conditions and methods in this and other colleges. The former scheme failed in its purpose, as, either because of excessive requirements or for some other reason, it did not influence a sufficient number to make it effective as a stimulus to the College at large. In comparison with other colleges fewer men of the same grade of work received recognition in the assignment of college honors. The new scheme attempts to make honors possible and attractive to a large number of men, and to make an equitable basis of comparison with other colleges. A careful estimate indicates that without allowing for the effect of any stimulus that may be exerted by the scheme, about twenty per cent of the College may be included in its operation. The scheme provides for an extension of the present "Honorable Mention " and of " Honors," which are changed to "Departmental Honors." "Degrees with Distinction" are greatly enlarged in their scope and rest upon general scholarship. An " Honor List" has been added,which recognizes general scholarship and also successful work in the departments. Its details will be seen by comparing it with the former scheme on pages 217-221 of the last catalogue.

For excellence in special departments of study, three grades of honors shall be awarded by the faculty: Honorable Mention, Departmental Honors, and Highest Departmental Honors.

Honorable Mention shall be awarded to students who shall attain an average rank of 90 in the courses specified, instead of 92 as heretofore.

Departmental Honors shall be awarded to students who attain an average rank of 90 per cent in courses specified in the past for Honors, for which 92 per cent has been required.

Highest Departmental Honors shall be awarded in departments specified, to those who fulfil the conditions hitherto attaching to the requirements for Special Honors, but on the basis of a 90 per cent requirement, instead of a 92 per cent.

At the close of the college year an Honor List shall be made out for all the classes, based upon the work of the year, and divided into three groups.

The First Group shall include those who have attained a rank of 90 or above in 18 semester hours of the work of the year, and have not fallen below 80 in any course in either semester, and also those who have obtained Honorable Mention in two departments during the year and have not fallen below 80 in any course in either semester.

The Second Group shall include those who have attained a rank of 85 to 90 in 18 semester hours of the work of the year, and have not fallen below 75 in any course in either semester, and also those who have obtained Honorable Mention in one department during the year, and have not fallen below 75 in any course in either semester.

The Third Group shall include those who have attained an average rank of 80 to 85 in the work of 18 semester hours in the work of the year and have not fallen below 70 in any course in either semester.

Students who attain a rank of 90 shall be designated " Rufus Choate Scholars".

Six members of the graduating class shall be appointed to speak at Commencement. To the two who attain the first and second ranks shall be asigned the orations ranking as the valedictory and the salutatory. The other four speakers shall be selected by the Committee on Commencement from those who receive degrees with distinction.

Any student who shall have an average rank for his entire course of 80 percent shall receive a degree cum laude.

Any student who shall have an average rank for his entire college course of 85 per cent shall receive a degree magna cum laude.

Any student who shall have an average rank for his entire college course of 90 per cent shall receive a degree summa cum laude.

The Honor List of the senior class, and also all other Honors which members of that class may receive, shall be printed on the Commencement program. The announcement of the Honor Lists of the other classes and also of their other Honors shall be made at a meeting of the College to be held in Webster Hall within the last ten days of October in each year, and all Honors shall be printed in the annual catalogue.

By two votes at recent meetings, the trustees have added materially to the attractions of life upon the Dartmouth faculty, and the action at the same time makes for increased efficiency throughout the whole instruction corps. An annual appropriation has been promised by which it shall be possible for the various departments of the College to be represented at the meetings of the learned societies ; and the plan for sabbatical year leave of absence has been supplemented by authorization of an option of semester leave of absence, at full pay, once within seven-year periods. Both of these plans are of particular advantage to a college situated as is Dartmouth. The isolation, which in so many ways is its strength, is in remoteness from library facilities and inter-collegiate fellowships a handicap to faculty achievement, and even to professional enthusiasm. The plan for a somewhat general representation of the faculty at meetings where associations with fellow-workers at other colleges will be possible will make for wider acquaintanceships and consequent benefits. The provision for semester leave of absence at full pay, where preferred to the provisions for sabbatical year leave, opens possibilities for advantages heretofore denied to many men. Under this, it becomes feasible for a man without independent means to take periodically seven to eight months for special work upon his subject. The satisfaction with which the announcements of these two votes have been greeted indicates the needs which have been met.

A communication of unusual viewpoint in criticism of undergraduates appears in the correspondence columns of The Nation for March 25. Written by a Princeton junior, it may be taken either as a bit of frank confession or as a brief jeremiad from one who, while in the undergraduate world, is not wholly of it and for the nonce has donned the prophet's robe to reveal his fellows to the world and to themselves. The spirit of his criticism is apparent in the following quotation :

"The undergraduate regards himself as a mature and important personage, who, for reasons of his own, has elected to live for a few years with some hundreds of thousands of personages almost as mature" and important as himself, in a community where the conditions of life are as favorable as, and in some cases much more favorable than, those he has been accustomed to. The only drawback to the delightful scheme, with its great freedom from disciplinary restraint, lies in the fact that each of these communities is encumbered by a number of men, called the faculty, who are so far advanced in age, or so biased in opinion, as to be utterly incapable of comprehending the ambitions of the full-blooded college man. As far as possible, the undergraduate ignores this superannuated body and applies himself with vigor and enthusiasm to the real affairs of life — the making of a team, the election to a club or fraternity, the aquisition of a reputation as a good fellow or a hard drinker, according to his tastes and talents — in short to becoming a 'big man' in some branch or other of the college activities. That expression 'big man' nearly every one can remember having used at the boastful age when one dons his first trousers and scalps his sister's doll as a proof of manliness. 'l'm not a baby, I'm a big man.' Likewise, the undergraduate, 'I'm not a callow boy with an unformed mind and a half-formed character, but I'm a big man with important matters on my mind.' "

It would doubtless be an advantageous thing all around if undergraduates would weigh this criticism of one who is of themselves, for the spirit criticised exists in the colleges with such constancy as to be always in evidence when either discontent at life in general or a lull in usual activities occurs. The tendency is not absent among students to believe that the theories of the undergraduate body, which at most has not been studying college conditions for as long as four years, should govern the actions of administrations and faculties which are making a life-study of such conditions. It is not always understood by students that failure to allow undergraduate opinion to govern official action does not necessarily mean that undergraduate opinion has been ignored. But in the end college men are fair, and for this reason the generalization of the Princeton undergraduate should be taken as a protest against exasperating tendencies rather than'a comment on fixed conditions.

As a matter of fact the undergraduate is neither the boy who '' dons his first trousers" nor the "mature personage," but he is in varying degree an inconsistent, sometimes irritating, and always interesting combination of the two. He is a complex of warring tendencies; full of conscious independence and subconscious timidity, of outward indifference and inward ideality, of apparent inflexibility and actual plasticity. Hardly any two of them have the same interests, capabilities, mental or moral characteristics. Few of them are moved by definite purpose, beyond that of securing a college degree and of becoming in some intangible way that indefinable but yet distinct product—a college man. The perplexities of the problem thus presented are clearly enough recognized. Failure of successful solution seems to lie either in placing too much responsibility upon the undergraduate or of placing too little. Very few of those far older and more experienced than he are to be trusted with freedom from fixed requirements. On the other hand, severe compulsion easily begets indifference or even revolt. It is a wise father who, as his son reaches the verge of maturity, ceases to lay stress upon parental authority and assumes the attitude of counselor and friend ; so too is it not a wise faculty that, in the midst of the claims of scholarship, perceives that the student is a very human being, in need now of stimulation, now of repression, and usually ready enough to accept them when applied with a kindly firmness, free from any spirit of contempt or distrust?

Exaggerated as the undergraduate statement before quoted seems, both in its expressed opinion of the students and in its interpretation of student attitude toward the faculty, there is enough truth in it to provide a helpful side light upon definite troubled situations in the college world. For if the undergraduates in any considerable number look upon the faculty as a herd of antediluvian donkeys ; it is safe to assume that a fair proportion of this faculty sharing the belief of this ironical correspondent, will look upon the undergraduates as an aggregation of undisciplined small boys. It is a matter of cause and effect ; though which is cause and which effect would be difficult to determine. In any event, given such a situation, the end of education is bound to suffer. There can be no common ground of friendly or profitable intercourse ; the small boy will carry stones in his pocket, and the donkey will present a stern pair of heels to every approach.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SIXTY-FIVE YEARS AGO

March 1909 By Harvey C. Wood, '44 -

Article

ArticleREMINISCENCES OF A GRADUATE OF 1812

March 1909 By Clinton H. Moore, Esq., '74 -

Class Notes

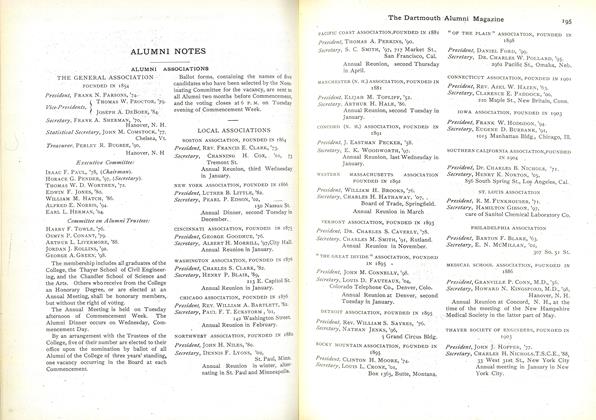

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1909 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

March 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1846

March 1909 By J. W. Barstow, -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

March 1909