The entrance upon my ninety-first year, and the receipt of the BI-MONTHLY, have put me into a reminiscent mood respecting our beloved almamater as she was sixty-five years ago. I can tell better what constituted Dartmouth College then, than what it is now, though at the Webster Centennial I was present and saw the great improvements in buildings and equipment which had been made.

When I was there in '40-' 44 the buildings were Dartmouth, Wentworth, Thornton, and Reed, the Medical School and Moor's Charity School for Indians, only. In this school in 1839, a summer term of nine weeks, I received the most critical training under one Brown, that I ever received in Latin and Greek. That summer Reed Hall was built.

I entered college in the fall of 1840, after reading most of my preparation without a teacher.

It would be pleasant to speak particularly of everyone on the faculty, but space would not allow. Our President, Nathan Lord, we all respected and loved, — all at least who respected dignity, scholarship, prudence, and piety. Some of us who were radical on the slavery question did not follow his lead. Although it was unjustly asserted by some hostile to him that his position was by pleasing the South to gain students, most of us knew him to be too honest to swerve from his convictions of what he considered to be right.

After several addresses on Slavery, one morning as we entered the Chapel for prayers, we observed a huge negro hanging in effigy over the face of the clock, with a tin hern six feet long under his arm. In those days horn blowing on dark nights was not uncommon. The President arose to read the scriptures and the smiles of the students subsided. After a unique prayer — all his prayers were unique - instead of waving a dismissal with his hand, he said in his slow enunciation, "Gentlemen, I perceive that one of the characters who have disturbed the quiet of our village of late has been been suspended, and I would suggest that his associates may come to the same condition unless they spedily mend their ways." Then, seriously, he gave some further warning. This was the only time I ever heard him say anything to cause laughter.

Another morning he went to his desk and found his Bible missing. But he arose and repeated the first Psalm with such power and simpleness that all were impressed, the prayer that followed was charged with grief. If the one who removed the Bible was there, he must have had great self-control to conceal his guilt.

The senior professor was Charles B. Haddock, — tall, dignified, polite, scholarly, an eloquent preacher, an orator. He was after appointed Minister to Spain. Professor Young, of natural philosophy and astronomy, was the honored father of the more noted professor of astronomy. I often called on him as I was particularly interested in his subject, and I remember seeing a fairhaired boy who I presume became the noted astronomer.

Alpheus Crosby was author of a Greek grammar, which as textbook I used many years in teaching. The critical, genial, and smiling professor! A few years later he resigned, giving as his reason a change in his theological views-His resignation was accepted, though I do not see what connection there was between theology and teaching Greek. I do not believe there has been a better teacher in Greek since. Our professor in Latin was Edwin D. Sanborn, — open faced, prompt, at times humorous, but always ready even as he wished us to be.

Professor Hubbard was of the departments of chemistry,geology,and mineralogy. The professors earned their salaries in those days! I never knew one of his experiments to fail. Doctor Peasley should be named, an able lecturer on anatomy and physiology. President Lord had much teaching to do in "Paley-Edwards on the Will," but some of us did not take it all in, though no one, it is to be feared, tried to force the will. Professor Brown had a fine personality and a pure literary style. Professor Chase was in mathematics, — tall, slim, sandy complexion, red hair. It was difficult for him to control his countenance, whether pleased or otherwise. He was a trial to some of us who with undergraduate unfairness said that he was partial. My room-mate said to me, "You are always right and I am always wrong," but my room-mate was, I know, easily "rattled" and the professor was a fine teacher and entirely fair I know.

I now come to the tutors of our freshman year — Samuel Colcord Bartlett (subsequently President) and Joseph Bartlett. We called them Tutor Sam and Tutor Joe. — not out of disrespect, but for convenience. Tutor Sam was tutor of algebra and geometry, Tutor Joe of Latin. One book was Ovid's "Metamorphoses." One student was called to translate a sentence commencing. " Quiputaverit, etc," "Who would think that a chicken would come out of the middle of an egg?" But by a slight mistake he made the metamorphosis still more wonderful. The genitive of ovum being 'ovl," and the dative of "ovis" being "ovi" he put sheep for egg to the merriment of the class, including the tutor. A couple of years after the office of tutor was abolished, as we learned from the Dartmouth, our college magazine — with this conundrum, "Why will there be no horn-blowing next year?" Answer: "Because there will be no tutors.''

The catalogue now issued is voluminous, greatly different from the one that we had. But once the catalogue was so inferior that the entire student body was unwilling to receive it. It was covered with a brown or drab color and trimmed by the binders so the pamphlet was about one-half inch wide. There was, as a result, an indignation meeting called. This was, I think, in 1842. Fiery speeches were made. A senior by the name of Jackson took the stage after calls, and with the greatest scorn attacked the thing called the "Catalogue of Dartmouth College." He carried gestures to extreme. Standing upon his toes ready to whirl, he extended the catalogue and in a high key exclaimed, " That a Catalogue of Dartmouth College ! — why it is not fit- for an infant school in Patagonia!", at the same time whirling entirely around on his toes. The result, a new edition of more respectable appearance was printed by the students, but I think we paid for the old one, too.

"Did you play football?" Yes, we did. But not as the few do now. Great improvements have been made, I suppose, since the simplicity of that time. We played en masse quite democratic, Seniors and Freshmen on one side, Juniors, Sophomores, and Medics on the other. The ball was placed in the center of the Campus and one kicked it and there was a rush to get it, and when one caught it he had a chance to kick. As it was rolling on the ground there were so many running together and kicking that shins were sometimes barked, but with no permanent injury. It was hilarious fun. Some would raise the ball entirely over the heads of the opposite party into the street. My classmate. Edward W. Clark, the foster-father of Clark, the founder of the Christian Endeavor Society, could raise the ball wonderfully. He was a great athlete. About five years ago I read of his death, and it was said he died of old age. I was curious to know how old a man must be to die of old age, so I referred to my book of autographs and read : "Edward W. Clark, Tewksbury, Mass., born Oct. 6, 1820." I was born at Portsmouth, N. H., March 25, 1817. He could kick a ball much higher than I, as he had greater skill; but in sawing wood and mowing grass I think I would have been a match for him. In my sophomore year I had a fine chance to raise the ball, but I made a slight mistake and instead of hitting the pigskin I hit the earthly ball, and not having a "place on which to stand" it did not move, but my ankle was sprained; so for a time I was hindered in my search for botanical specimens, with John M. Ordway, over the hills and through the valleys of Dartmouth. I have not played football since.

At that time no classes in botany were formed at Dartmouth, and I know of no one except Ordway and myself that studied botany practically. You will find the region around Dartmouth a rich and varied field for the botanist. If you want to find the yellow lady's slipper, go over into those dark woods east, where Ordway and I danced like children at the discovery. Thread the "Vale of Tempe" and you will find numerous delicate plants. You will be careful how you grate the arum root to ascertain how much starch there'is in it. One day I noticed that Ordway's hands were badly swollen and inflamed. "What is the matter?" I asked. "I grated some of the roots of the arum to ascertain the amount of starch," said he. When the root is dried its poisonous quality disappears and it is useful as a medicine.

I have just received a letter from Ordway and he refers to an axe that I loaned him to cut his way out of his room, if imprisoned by some of his classmates. Ordway was the bell-ringer, and the monitor of the second division of our class. One morning he attempted to get out of his room, but could not open his door for it was fastened on the outside with a rope, but he readily took a panel out of the door and rang the bell in good time, while some of his keepers were in bed, and he was present to mark their absence. A few mornings after, he found himself so imprisoned by many doors taken from unoccupied rooms in Dartmouth Hall that he was unable to get out. He had a closet, out of his room, in which he had piled his wood. He mounted the pile of wood, broke the plaster and laths overhead, crawled up through and went to a scuttle hole from which pended a ladder attached with hooks; but either by design of his captors or by accident the lower end of the ladder was put up to a hook to be out of the way. One of the rungs of the ladder was directly across the scuttle hole so it was impossible to let himself through. But he had a pocket knife and with all haste he cut one end of the rung, hard oak wood, and in his haste he broke the large blade of his knife; and then with the small blade more carefully finished cutting it off. Then he broke the rung out, let himself through, and seized the bell rope just in time. After we came out I heard some remark made which led me to believe they had not given up their design to imprison the bell-ringer;and I told Ordway, while he was showing me his blistered hand, That they would probably try it again: "I have an axe which you may take by night to your room and conceal in your straw bed. Then with all the doors they can collect against your door you can cut your way out." But they never tried it again.

But perhaps I have already spoken too much of minor things, though of many things I would like to speak. My young brothers of Dartmouth may well rejoice over their splendid buildings and eminent instructors! We had to make an effort to stand respectably as scholars, and with all their equipment the men today must yet dig to secure valuable mineral. I congratulate them, living at such a lime. They are entering a century of mighty achievements, and I trust that they feel their responsibility so as to do their utmost to meet the demands of the age. And when they have passed ninety I hope that they may look back with regret at only a minimum of wasted effort, and that in the main their thoughts may be of lives well spent, justifying the preparation they have received.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA year ago certain regulations were adopted

March 1909 -

Article

ArticleREMINISCENCES OF A GRADUATE OF 1812

March 1909 By Clinton H. Moore, Esq., '74 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1909 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

March 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1846

March 1909 By J. W. Barstow, -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

March 1909

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident's Addresses

June 1931 -

Article

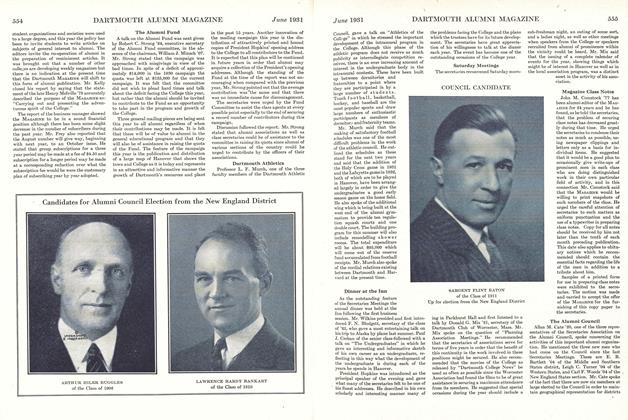

ArticleFor Trustee The U.G.C.'s Choices

March 1981 -

Article

ArticleAnd the Winners

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

April 1946 By H. L Duncombe Jr. -

Article

ArticleThe Compass Points North

November 1953 By R. L. A. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

DECEMBER 1963 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29