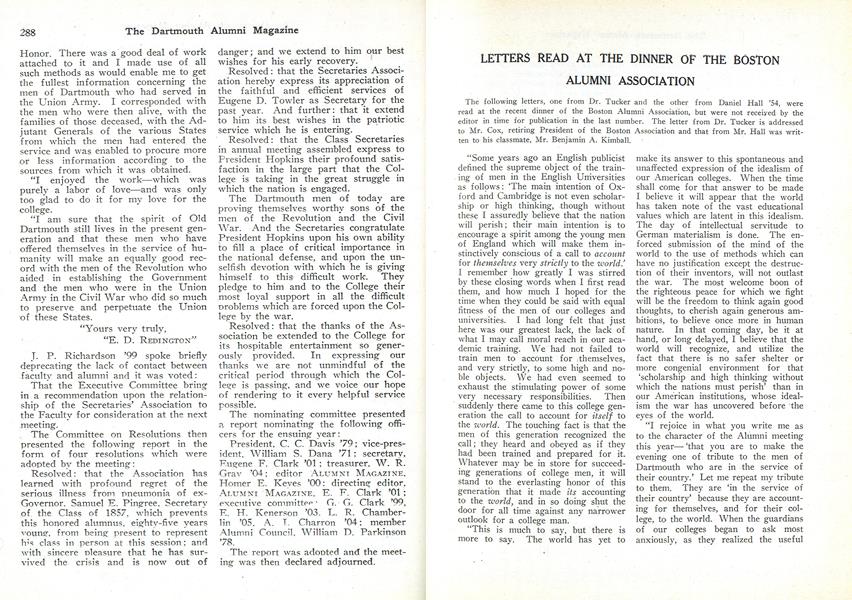

The following letters, one from Dr. Tucker and the other from Daniel Hall '54, were read at the recent dinner of the Boston Alumni Association, but were not received by the editor in time for publication in the last number. The letter from Dr. Tucker is addressed to Mr. Cox, retiring President of the Boston Association and that from Mr. Hall was written to his classmate, Mr. Benjamin A. Kimball.

"Some years ago an English publicist defined the supreme object of the training of men in the English Universities as follows: 'The main intention of Oxford and Cambridge is not even scholarship or high thinking, though without these I assuredly believe that the nation will perish; their main intention is to encourage a spirit among the young men of England which will make them instinctively conscious of a call to account for themselves very strictly to the world.' I remember how greatly I was stirred by these closing words when I first read them, and how much I hoped for the time when they could be said with equal fitness of the men of our colleges and universities. I had long felt that just here was our greatest lack, the lack of what I may call moral reach in our academic training. We had not failed to train men to account for themselves, and very strictly, to some high and noble objects. We had even seemed to exhaust the stimulating power of some very necessary responsibilities. Then suddenly there came to this college generation the call to account for itself to the world. The touching fact is that the men of this generation recognized the call; they heard and obeyed as if they had been trained and prepared for it. Whatever may be in store for succeeding generations of college men, it will stand to the everlasting honor of this generation that it made its accounting to the world, and in so doing shut the door for all time against any narrower outlook for a college man.

"This is much to say, but there is more to say. The world has yet to make its answer to this spontaneous and unaffected expression of the idealism of our American colleges. When the time shall come for that answer to be made I believe it will appear that the world has taken note of the vast educational values which are latent in this idealism. The day of intellectual servitude to German materialism is done. The enforced submission of the mind of the world to the use of methods which can have no justification except the destruction of their inventors, will not outlast the war. The most welcome boon of the righteous peace for which we fight will be the freedom to think again good thoughts, to cherish again generous ambitions, to believe once more in human nature. In that coming day, be it at hand, or long delayed, I believe that the world will recognize, and utilize the fact that there is no safer shelter or more congenial environment for that 'scholarship and high thinking without which the nations must perish' than in our American institutions, whose idealism the war has uncovered before the eyes of the world.

"I rejoice in what you write me as to the character of the Alumni meeting this year— 'that you are to make the evening one of tribute to the men of Dartmouth who are in the service of their country.' Let me repeat my tribute to them. They are 'in the service of their country' because they are accounting for themselves, and for their college, to the world. When the guardians of our colleges began to ask most anxiously, as they realized the useful human costs of war, What shall we do with our colleges; shall we sacrifice them to present demands of duty, or shall we save them for the uses of the future: the answer came from the very men to whom we are paying tribute tonight, as from the great host of their comrades from other colleges,—We have chosen the path of sacrifice, not the path of safety. In our calm afterthought we see not more clearly the heroism than the wisdom of their answer: we now see that the path of sacrifice was, and is, and must be to the end, the only path of safety.

"Very sincerely,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

April 1918 -

Article

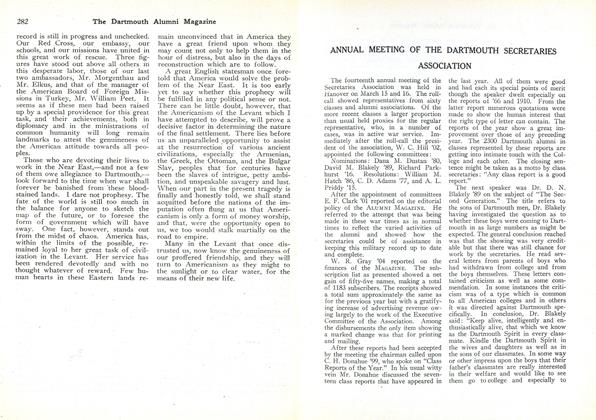

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1918 -

Article

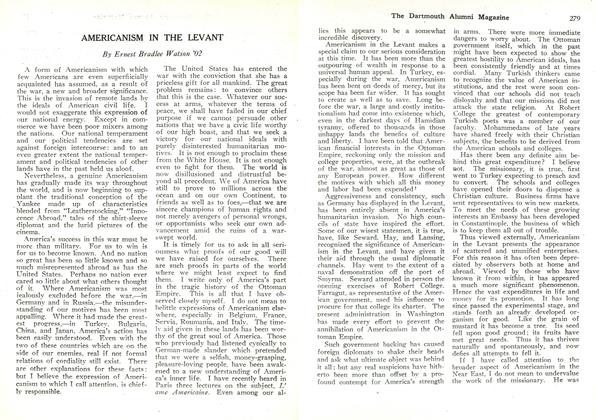

ArticleAMERICANISM IN THE LEVANT

April 1918 By Ernest Bradlee Watson '02 -

Article

ArticleMr. Watson's article in this number of the MAGAZINE on "Americanism

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleTWO LETTERS FROM THE FRONT

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF LIEUTENANT EADIE '18

April 1918 By FRANK N. HUME

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA SKI RUNNER AND AMBULANCE DRIVER IN FRANCE

December 1916 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorGRADUATES OF MIDDLE EIGHTIES MAY HELP PROF. McCALLUM

June 1925 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor Negro Impostor

March 1931 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

October 1961 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorHave a Nice Millennium

MAY 1996