President Pritchett, in his last annual report of the Carnegie Foundation, analyzes the loud complaints of the colleges that the schools fail to give good preparation for college, and the bitter retorts of the schools that the interference and domination of the colleges in high school affairs has "reached a degree of intolerable impertinence." One of the chief obstacles to a proper cooperation between the college and the secondary school is due, he thinks, to the fact that "there is even yet little contact between college teachers and secondary school teachers, and little opportunity for either group of teachers to realize how mutually dependent these two institutions are. It is not easy to bring the college teacher into contact with the large number of secondary teachers in a great state; and for this very reason the obligation of the college 'to study the secondary school system and to bring itself into sympathy with secondary school conditions is all the greater."

This is precisely one of the purposes which Dartmouth for eleven years has been trying to accomplish by its Annual May Conference of school .and college teachers. This year, for instance, the program for each discussion contained some speakers from colleges and some from secondary schools. There was an excellent opportunity for that free interchange of opinions from the college and from the school which President Pritchett rightly deems important. The Conference was attended this year, aside from members of the Dartmouth faculty, by seventy-three teachers representing six different states, seven different colleges and universities, and a large number of high schools. More than half of the teachers came from outside of New Hampshire.

The first May Conference, in 1900, was devoted to a consideration of the teaching of History. In the following years the other subjects of the school curriculum, Latin and Greek, English, Mathematics, French and German, Physics and Chemistry, and also the broader questions of the Development of Character, Vocational and Physical Training, and College Entrance Requirements were discussed in annual conferences. This year the cycle swung round again to the study and. teaching of History. The College was fortunate in being able to secure the attendance and cooperation of the New England History Teachers' Association. This active organization held its annual spring meeting as a joint session with the Conference; it provided part of the program and assured the attendance of some of the ablest and most successful teachers of History and Civics in New England.

The, Conference opened on Thursday evening, May 11, with an address.by Professor George L. Burr of Cornell on "History as a Teacher and the Teacher of History." With his characteristic charm of manner and keenness of insight, Professor Burr suggested that History, properly regarded, is something broader than what the pupil: studies in the ordinary text-book. It is the experience of life of each one of us; it begins when the mother first amuses her child by telling her something of her own early childhood, and when the child begins, to manifest an appetite to hear of things, real or imaginary, in the world about him. The little child wants history which has action; he is fascinated by the action of the cow jumping over the moon. A year or two later he is conscious of his own efforts, and yearns to hear of the human efforts of others, —of Jack and the Bean Stalk. Later still the romance of brave princes and beautiful princesses is all absorbing. Then, with school days, the appetite changes to a desire to be admitted to the simple chronicle of the pains and pleasures of the boy around the corner or the girl next door. As his mind develops and his horizon extends to a larger world, he gradually comes to think of groups of human beings, of the city, state, and nation, and to love to learn of what we more often in a narrower view think of as History. The teacher of History must seek to suit the proper food to these changing appetites which correspond to different stages of growth; and at all times he has the opportunity and the duty of stimulatingimagination, enthusiasm, sympathy, and a love of truth.

The session of Friday morning was devoted to a consideration of the "Report of the Committee of Five of the American Historical Association on the Study of History in Secondary Schools." This report suggests a modification of that of the "Committee of Seven" of "a dozen years ago. The new suggestion is that the subject matter of the four years' high school course in history be divided as follows: (1) Ancient History to about 800 A. D.; (2) English History, with some account of the "high peaks" of European and Continental Histriy, to about 1760; this course would also include the beginnings of colonial settlements; (3) Modern European History, including English History from 1760; and (4) American History and Government. The discussion was opened by Dr. James Sullivan, who spoke with authority as 'being one .of the Committee of Five, and from experience as principal of the Boys' High School of Brooklyn, N. Y. He was followed by Professor Lingley of Dartmouth, Professor Hazen of Smith, Principal Swett of Franklin, N. H., Professor Burr, Mr. Taylor of Vermont Academy, and many others. There seemed to be a very general approval of, and enthusiasm for, the changes recommended in the Report of the Committee of Five. It has the advantages of eliminating from the four years' school course the very difficult second year course in Mediaeval and Modern European History; it makes the settlement of the thirteen American colonies a part of English' and Continental History, as it really was; and it secures more time for the important subjects of recent European History and American History and Civil Government. On the other hand, it does not leave the pupil wholly ignorant of Charlemagne and Innocent 111, nor of Mohammed and Luther; he learns something of these great men in connection with the new second year course, whose main work, however, is to be centered around the comparatively simple thread of English History.

After a luncheon, tendered to all visiting teachers by the College in College Hall, Friday afternoon was devoted to 'the perennial question of college entrance requirements. Professor Foster of Dartmouth, as chief examiner in History of the College Entrance Examination Board, explained how the papers in History set by the Board are made out, and suggested how teachers in the schools might cooperate still more with the work of the Board, by submitting questions, by urging pupils who have completed a subject to take the examinations of the Board, or by even using the Board examinations as part, if possible, of the regular school examinations. Professor Fay of Dartmouth explained some ' recommendations which Dartmouth has made to, the New England College Entrance Certificate Board. Most of these' recommendations have now been adopted by the Board and will make it easier for the small but good school to secure the certificate privilege provisionally for a year. The chief interest of the afternoon centered in the new system of entrance requirements at Harvard, which was explained by one of its principal authors, Professor W. B. Munro. Professor Chadwick of Phillips Exeter Academy opened the discussiori from the point of view of the teacher who prepares pupils for college.

On Friday evening, Professor C M. Andrews of Yale, at the invitation of the New England History Teachers' Association, spoke very interestingly on "The Value of London Topography for American Colonial History," explaining, for instance, that one of the reasons for the extraordinary inefficiency of the English Navy in the century before the American Revolution lies in the fact that the daily business of the admiralty was transacted in thirteen different arid widely separated offices in London, each managed often by mutually jealous and insubordinate officials. " Similarly, other sides of English Administration in our colonial period are to be satisfactorily explained only by a minute study of the location and relation of the various administrative boards in London.

On Saturday morning the members; of the Teachers' Association had a valuable discussion of "Outside Reading and Note Books," in which many teachers gave a frank statement of the successes or failures of various methods which each had tested by practical experience. It seemed to be generally agreed that "outside reading" could be done in reasonable 'amounts; that it was one of-the most valuable parts of the work in History; that it was one of the parts of the work which gave to the teacher of History the opportunity to develop those qualities' which Professor Burr two nights before said it was our duty and privilege to develop; and that it was what made it more possible for History than for most other subjects in the school curriculum to "be all things to all men."

Sometimes at conferences of this kind, zealous teachers make so prominent the difficulty of their problems and of the attainment of their high ideals that the atmosphere at the close of the meeting is one of discouragement. Fortunately, this was not true at this meeting. As the teachers left Hanover they seemed rather to realize what a great advance they had made in the last few years, and that, though though there is still untold room for improvement, they had nevertheless made very hopeful progress.. Another very encouraging and favorable sign, which was reflected again and again in the discussions, 'was the fact that so many teachers felt such confidence in themselves, that so many had struck out lines of their own, and that there seemed to be such a general agreement that it was not necessary or desirable to follow rigid systems and schedules of work, but that teachers ought to be free to adapt their work in accordance with their personal bent or ability or in accordance with focal conditions.

Many teachers expressed their pleasure at the opportunity of seeing our College in the beautiful first green, of warm weather. They had an opportunity to see the new buildings, Webster, Parkhurst, and the new Gymnasium, and to stroll to the river over the Country Club or to see a track meet with the Institute of Technology. One evening there was an informal reception in the newly established Graduate Club, and another evening in College Hall. Says a letter which I received this morning and which I think expresses the feeling of many of those who attended the Conference: "I thoroughly enjoyed every minute of my stay, and was much impressed both by the College and by its pleasant surroundings. It is very easy to understand why Dartmouth men grow fond of their little town among; the hills."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis number of THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE

June 1911 -

Article

ArticleMEETING THE PROBLEM OF COLLEGE ATHLETICS

June 1911 By W. Huston Lillard 1905 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1911 -

Article

ArticleThayer and Tuck Graduations

June 1911 -

Article

ArticleMedical Graduates Placed

June 1911 -

Article

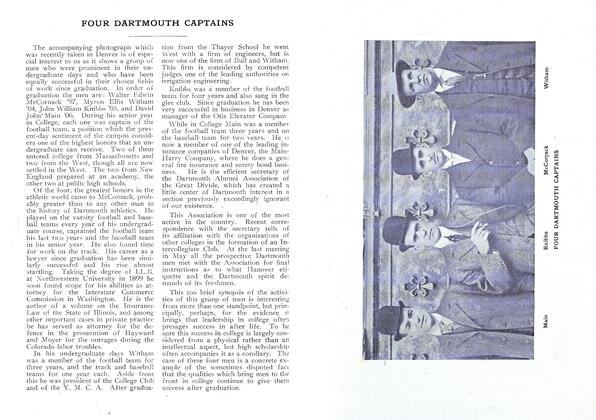

ArticleFOUR DARTMOUTH CAPTAINS

June 1911

Article

-

Article

ArticleScholarship in the College

April, 1911 -

Article

ArticleAddresses by Pres. Hopkins

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Article

ArticleFall Trustee Meeting

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

JUNE 1959 -

Article

ArticleField-Tested Tips for Handling an Angry Gorilla

SEPTEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

January 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45