in Hanover has darkened so much of the sky that the anxious alumnus might well be pardoned for believing the entire heavens obscured. Such, however, is not the case. At least fifty per cent of the undergraduates are going their serene way, undisturbed by the factional bickerings of the elect, who are making a rather disproportionate amount of rumpus, and attracting an entirely disproportionate amount of attention. But even here the fault is not to be attributed to total depravity. Part of it, no doubt, is the outgrowth of the primal instinct of self-preservation asserting itself in over-housed and under-financed fraternities which are, in consequence, unable to see good in any arrangement which does not primarily benefit themselves. A larger part is due to an undergraduate striving for perfection, which seeks to attain its end through the feeble medium of legislation. The difficulties of the whole matter are considerably increased by the fact that fraternity life at Dartmouth is, as pointed out in THE MAGAZINE for August, undergoing a transformation, both of method and of ideal.

With all the turmoil and its unfortunate accompaniment of exaggerated publicity, the Administration has shown admirable patience and restraint. The warring factions have been given every opportunity to compose their differences and to evolve a constructive and sensible program of action. Failing in this, they have been met with a quiet but determined assurance that the College is greater than the fraternities and that, if the latter can not make terms, the former will be obliged to interfere conclusively. There can be no question that in this attitude the Administration has the unqualified backing of trustees, faculty, and alumni. Best of all, there is no thoughtful undergraduate who questions the justness of the position taken.

Such being the case, there seems no reason to expect undue prolongation of difficulties which have existed for some years past. For one thing, the fraternities have signed a truce and have ceased proselyting activities. The fact that one violation of the truce raised a violent storm of protest is, after all, but evidence of general good faith. For another thing, the impossibility of a short-season policy has become manifest; non-interference with the freshman's first semester begins to assume the virtue of a maxim. Thus, of the two horns of the dilemma the short horn has virtually been eliminated. The burning question is that of the due length of the other one.

Into this THE MAGAZINE has no intention of thrusting itself to the scorching point. It is, however, perhaps safe to point out that an early sophomore season presents nearly as many objections as an early freshman season. If chinning we must have,—and of that unfortunately there seems small doubt, - it would best be concentrated at a time when there is little else to think of, and when the attendant excitement will serve as an antidote for other and more dangerous ills. No Dartmouth man need be told what that time is: the black period between the going of winter and the hesitant coming in of spring. If effective measures can be found for nullifying fraternity performances during the first five months of the college year and for concentrating them during the bleak days of March, more than two birds—and perhaps some bottles—will have been brought down with a single stone.

The Independent Statesman, in its issue for October 17, comments as follows on the demise of the Dartmouth Literary Magazine:

"A news item that came out of Hanover the other day seems to us to indicate a rather serious lack in the new Dartmouth College with its 1,200 students and five million dollar plant. Teachers, scholars, and buildings are but the inert mass of an educational institution through which the varied spirit of ambition, endeavor, and culture must course to give it life and worth. .

"No one denies, of course, the existence of such life and worth at Hanover. The "Dartmouth spirit" has been acclaimed in speech and song from coast to coast.

"But when the news comes from Hanover that the Dartmouth Literary Monthly, after twenty-five years of creditable success, has been obliged to suspend publication because of lack of college interest and financial support we are moved to regret not only the passing of a worthy product of college" ate activity but the apparent absence of any activity on this line.

"Football heroes come and go but the best known Dartmouth name of the last three decades is that of Richard Hovey, poet, some of whose first verse appeared in the first numbers of the Dartmouth "Lit." In those days a student body of less than four hundred members filled the pages and paid the bills of a monthly magazine which was quite up to the collegiate level of the country in literary merit and inherent interest.

"We regret that the new and greater Dartmouth cannot do as well."

In this criticism there is no little truth. The condition is, however, less hopeless .than at first appears. Twentyfive years ago there was, throughout the country, more interest in literature, and in pseudo-literature, than there is today. In the period since 1885 numberless reviews, critical journals, sheaves of periodical essays, and the like, have passed'into the great beyond or have changed their character to that of gossiping guides to the best sellers, and anecdotal authorities on the habits of writers. Of the old-time literary magazines, one only, survives.

It is hardly strange that a condition characteristic of the country at large should find its parallel in the colleges. At Dartmouth it was frankly met in the recognition of the futility of continuing a publication that few wrote for and fewer read. Today the college "Lit" competes on too unequal terms with a host of rivals. It must either be heavily subsidized by unwilling advertisers, or die.

Yet the appreciation of literature and the desire to produce it are by no means extinct. They constitute a definite and vital part of college life and college activity. Whether or not they require the medium of type and printing press to make them truly effective remains to be seen. If they do, it is reasonably certain that means will be found for the reviving of the Literary Magazine, or at any rate of some publication that shall give expression to the needs of men who form a necessarily small, but none the less important, part of the student body.

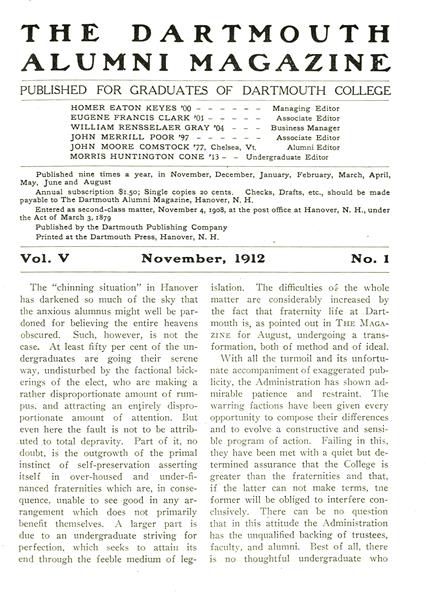

The frontispiece of this issue of THE MAGAZINE shows the Tirrell and Powers medals offered to Dartmouth graduates for best physical improvement. Three medals are offered, all of the same design, but executed in different metals. The Tirrell medal is of gold and is given as a first prize, the two Powers medals are respectively of silver and of bronze, and are given as second and third prizes. Such simple symbolism as the medals offer is that of strength seeking wisdom:—the athlete pausing to bend over the printed scroll. The graceful pine branch design of the reverse, which has space for receiving the engraved name of the recipient, has an application sufficiently obvious for Dartmouth men. The wish of the Committee which had the selection of these medals in charge, was to depart from the over elaborate and often cheap commonplaceness of the usual athletic medal, however expensive, and to secure something possessed of artistic propriety and value. The illustration bears witness to the very considerable success of their efforts, which were ably seconded by Tiffany and Company, of New York.

The reunion of the graduates of the Dartmouth Medical School, reported elsewhere, was unique, significant, and enjoyable.

They came from as far away as Pasadena, and from as far back as 1856. They were from institutions, from teaching and from editorial work, and from highly successful practice. Perhaps ten per cent were from metropolitan centers and another ten per cent from strictly rural practice; but the great majority were from the small cities of New England and the Middle States,—urban and urbane. They left us thirty, twenty, ten years ago for their hospital years, often under pecuniary stress, and, like the "medic" of the time the world over, not too particular about appearances. They came back showing all the refining effects of responsibility and prosperity. Their enthusiasm for the school in which they laid the foundation for their success, and their appreciation, after competition with others, of the efficacy of its thorough, hand-to-hand instruction was most encouraging and stimulating. And it all gave a new emphasis to the thought that in the plans for the future of the School the great interest which its alumni have in it must not be a minor consideration.

There has been no such gathering before ; may the future have many.

Particular attention is called to Professor Wicker's able article on "The College Teacher in Politics." As the author states, this article has been prepared at the express request of THE MAGAZINE, a request made for the sake of clarifying issues and positions too often misunderstood or misinterpreted. Professor Wicker states his case with a definiteness and vigor that leave no room for ambiguity. This does not mean that THE MAGAZINE agrees with him: at some points it does; at others, its disagreement is absolute. Yet to enter into written debate at the present time would be unfair to the writer and of no particular benefit to the reader. Fundamentally the question resolves itself into that of the true function of the college teacher. To this THE MAGAZINE proposes later to give some space. Meanwhile those who are minded to contribute material on the specific topic of discussion are cordially invited to do so.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE TEACHER IN POLITICS

November 1912 By George Ray Wicker -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEDICAL REUNION

November 1912 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

November 1912 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH NIGHT

November 1912 -

Article

ArticleTHE FRATERNITY SITUATION

November 1912 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS TO STUDENTS ON THE OCCASION OF OF THE OPENING OF COLLEGE SEPTEMBER 19, 1912

November 1912 By President Ernest Fox Nichols