One of my earliest Dartmouth memories is of a November snowstorm in my freshman year, in which I humbly and inconspicuously followed Dr. John Lord, the historical lecturer, around the Hanover streets, happy in the thought that I was looking at a man who had really written a book. Authors had not been unknown in my birthplace: the first thing I remember is being lifted to the ceiling—partly frightened and partly delighted—by that burly and now forgotten bard John G. Saxe; and John S. C. Abbott, the eulogist of Napoleon, had been a familiar sight to me; but still the literary man was enough of a rarity to make Dr. Lord a conspicuous object in the Hanover landscape.

Dr. Lord's voice was not melodious, nor was there much charm in his attitudes or gestures; and he knew no subject profoundly; but he did know more about many great characters in the world's history than most of his hearers, and his lectures so agreeably addressed the average mind that they attracted interested audiences for years, and still have considerable vogue in book form. Later, when I came to know him personally, his originality of- character made him a marked figure. He was an incessant smoker, having , a drawer-full of tobacco open before him for convenience as he wrote, and seldom appearing on the streets without his long pipe.

It has always been said that Dartmouth has produced statesmen, lawyers, ministers, and teachers, rather than literary men, and there is some truth in the remark. But I once counted the college graduates in a list of three or four hundred American authors down to 1878, and found that they had come, in numerical order, from "four leading institutions in order of age: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth; William and Mary having excelled in statecraft, not letters, and Columbia being rather unexpectedly in the background. A narrower list would still, because of its environment, give the primacy to Harvard, with Bowdoin a good second, by reason of that remarkable Hawthorne-Longfellow class of 1825; while if we restricted our examination to the four absolutely greatest American writers the distribution would be even: the romancer Hawthorne belonging to Bowdoin, the philosopher Emerson to Harvard, the orator Webster to Dartmouth, and the world-author Poe (as a student but not a graduate) to the University of Virginia.

The first edition of Baedeker's UnitedStates, issued in 1893, gives what I have ever since thought the finest list of Dartmouth's chief graduates to that date: Choate, Marsh, Chase, and Ticknor. Webster, with the possible exception of Burke, was the greatest orator since Cicero; Choate was our chief master of perfervid and strictly forensic speech; Marsh was the American pioneer in the thorough philological study of English and the Teutonic "languages and also a sound early investigator of the theme which he expressed in the apt title of his volume "The Earth as Modified by Human Action"; Chase was an early and powerful abolitionist, the shaping financier of the Civil War (unless that honor be given to Thaddeus Stevens, another Dartmouth man), and Chief Justice; and Ticknor, in some ways the most remarkable of the five save Webster, was the first American to develop the study of continental languages, to introduce the elective system, to start a truly great public library, and to produce a masterpiece of literary research.

We are not, therefore, following a feeble or unworthy literary trail when we look at the old Humphrey Farrar house on South Main St. (next Mr. Storrs'), where Webster roomed freshman and sophomore years; or the McMurphy house (Professor Skinner's), at the corner of Webster Avenue, his later abode; or the Leeds house, in which Choate was married. Similar interest may be aroused by looking at Marsh's little Icelandic grammar in the College Library; or Ticknor's life of Prescott, with the author's autograph presentation; or the well-known water-color sketch of the College made by him when an eleven-year-old sophomore.

The "passionate pilgrim" to Webster's loved small college may also go to the village cemetery and stand by the grave of his classmate Ephraim Simonds, over which Webster, in August of his graduating year, 1801, delivered a eulogy. It is not known where Black Dan gave his Fourth-of-July speech of 1800, requested by the citizens of Hanover when he was eighteen years old and a college junior. In that speech the boy outlined the argument for the indissolubility of the Union which he iterated for half a century.

The College Church, as we persist in calling it,'has at one time or another covered hundreds of celebrities, whom I need not try to recount. Of all the speeches its walls have heard the greatest are Emerson's "Literary Ethics" address in 1838. which George William Curtis called the masterpiece of,modern eloquence; and Choate's eulogy of Webster, 1853.

A. slightly inaccurate but interesting account of Emerson's appearance in the hyper-orthodox college of the time may be found in Holmes' life of the transcendentalist, - the author who came here for two years as lecturer in the Medical College, saying that a liberality which fluttered the dove-cotes of Cambridge must have sounded like the crash of doom to the timid inhabitants of the Hanover aviary. Holmes also describes Hanover in a page of the "Autocrat": blue Ascutney at one side, the hills of Beulah at the other, and Colonel Brewster leading the Commencement procession. The caravansary where Ledyard launched his canoe is elsewhere described by Holmes in the second line of his condensed stanza-biography of Webster:

"A roof beneath the mountain pines; The cloisters of a hill-girt plain; The front of life's embattled lines, A grave beside the sounding main."

It is interesting to remember that the radical Emerson, who was then deemed a dangerous heretic by Andrews Norton, Henry Ware, and other "Channing Unitarians" of. the Harvard Divinity School, was invited by the students to address the "United Literary Societies," as their fourth choice, after a heated season of senior politics. Another iconoclast who was given an earlier chance at Dartmouth than in most other places was Walt Whitman, who came as the Commencement poet of 1872, leaving been elected by a majority of the senior class with some idea of "spiting the faculty". But he came and went harmlessly, having been entertained at Doctor Leeds' house and having delivered a poem which was partly inaudible. The story of his stay, plus a frank "puff" of himself, unsuccessfully written by himself for newspaper publication, is given in Bliss Perry's life of the "good gray poet". The history of literature contains no more amazing illustration of the egotistic idea which Petroleum V. Nasby once jocosely expressed to me, speaking of one of his own productions: "I know that's a good thing, for I wrote it myself!"

Webster, Holmes, Hale, Stedman, Boyle O'Reilly, Joaquin Miller, and many others have spoken in the church, as well as a company of notable men outside the political or literary walks of life, like Lord Dartmouth or Chief-Justice Fuller. Chief-Justice Chase and the other speakers at the Centennial of 1869 are associated with a big tent on the common, and the bigger thunderstorm that descended on it and them.

A Dartmouth Commencement is described in the novel "Miss Gilbert's Career", by the once popular moralist and would-be poet, Josiah Gilbert Holland. Education of a different sort, that given to girls in the "nunnery" which stood on the site of Webster Hall, forms the theme of "Susan Coolidge's" (Sarah C. Woolsey) "What Katy did at School." Just beyond is Wentworth Hall, in which Richard Hovey most cheerlessly roomed until his migration to Reed. I wish that some zealous searcher would go through the annual catalogues and start a scheme of putting up, in the older dormitories, the names of distinguished occupants.

Many famous men have graduated from Dartmouth and others have served her; but the list of eminent natives of the town is curiously small. Perhaps the three most famous are Laura Bridgman, the first deaf, dumb, and blind person to be given an education, whom Dickens so enthusiastically described in his "American Notes"; James Freeman Clark, at the time of his death the leading Unitarian minister of Boston; and Charles A. Young the astronomer, who did all his best spectroscopic work in our old observatory.

I remember hearing the late Samuel Eliot tell of the visit he made to a Dartmouth Commencement with Ticknor, Longfellow, George S. Hillard, and Samuel G. Howe. Doctor Howe's errand was to see the deaf, dumb, and blind girl of whom he had heard, whose home was in the eastern part of the town. The speaking exercises of Commencement, as described by Longfellow in his journal, lasted all day, and Doctor Howe left the rest of the party to endure the oratory as best they could. In the afternoon he burst in upon them with the elated cry: "I've got her, I've got her; they're going to let me take her to Boston to try to educate her." What followed at the Perkins institution everybody knows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth will welcome the Secretaries on March 14 and 15.

March 1913 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

March 1913 By WM. H. GARDINER '76 -

Class Notes

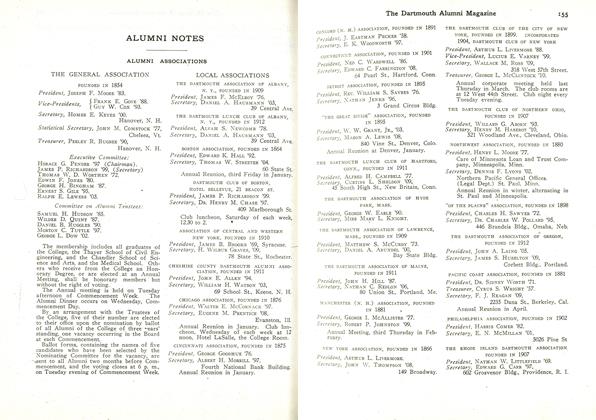

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1913 -

Class Notes

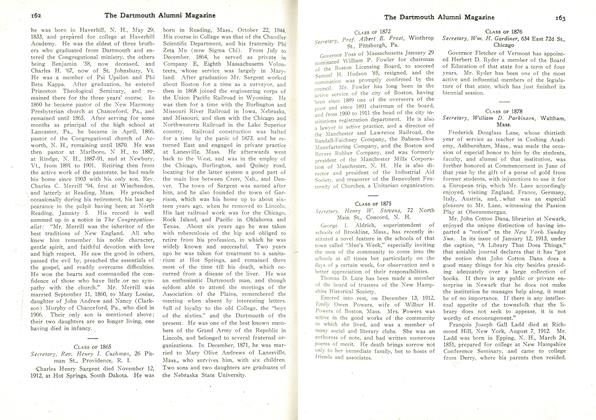

Class NotesCLASS OF 1878

March 1913 By William D. Parkinson -

Class Notes

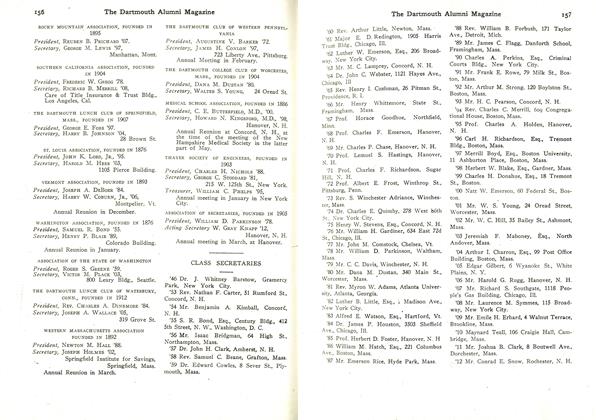

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

March 1913 -

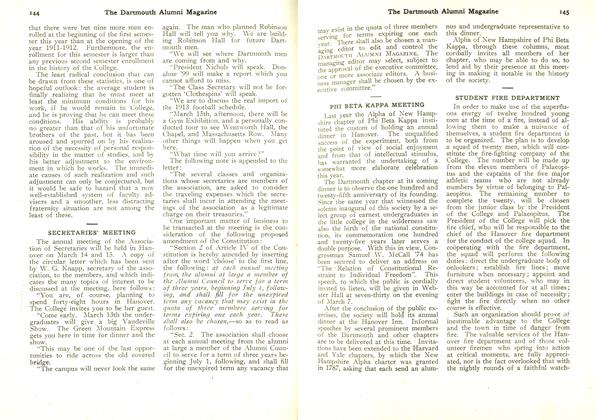

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES' MEETING

March 1913