Whether the gods are stirring up the college fraternities with a view to letting various legislation eventually destroy them, or whether the fraternities, mothlike, are continuing to career in the limelight merely because they do not know any better is a question of small moment. The important fact is that these undergraduate organizations seem to be steadily growing in disfavor and that in some parts of the country, notably in the middle West, their very existence has been seriously threatened. And now the action of Alpha Delta Phi in withdrawing the charter of the venerable Manhattan chapter transfers the agitation to the East.

Whatever the fundamental merits of this action on the part of one of the oldest and most influential of American fraternities and whatever the ac- tual motives that controlled the vote of the twenty-four chapters in the elimination of the one, the whole movement was, from the standpoint of policy, unfortunately timed. It has served to give wider publicity than ever to the middle West hostility to fraternities and simultaneously to provide exemplification of one at least of the grounds of complaint against them, namely, their lack of a truly democratic spirit.

For some little time to come the fraternities are likely to be on the defensive, not only against suddenly aroused college authorities but against the general public as well. They and their defamers will doubtless spill a good deal of ink in the course of altercation. Before the battle is fully on, it may be interesting to examine into the general conditions now existing, their causes and their probable outcome. Of the present of college fraternities' perhaps the less said the better. The past is undoubtedly illustrious, or at least creditable; the future promises large achievement. Just now, however, transitional processes are in operation and transition and trouble are nearly synonymous terms.

Fraternities in general appear to be in the unfortunate situation of having outgrown or outlived an earlier period of usefulness. At the outset, that is, back in the early '30s, when the oldest of them was founded, they were, to all intents and purposes literary societies, calculated to supply certain lacks in the restricted curriculum of pre-elective days. Their weekly meetings consisted of debates, orations, declamations and readings, often carefully prepared and eagerly listened to. The symbolic pin, the mystic hand clasp, the various other elements of secrecy were but a part of nineteenth century romanticism with no meaning or intent other than that of casting a glamour over entirely commonplace relations.

All this, of course, was before student time and thought were absorbed as now in a multiplicity of organizations. The recent upgrowth of undergraduate .newspapers and periodicals, debating and forensic unions, musical, dramatic and literary clubs, often with intercollegiate interests and affiliations, has so diluted fraternity activities in similar directions as to reduce them to the vanishing point. The community of intellectual ideals that originally brought men together has been gradually drained away until it has left the incidental social element as the sole residuum. If the fraternities have not altogether succeeded in making a satisfactory working basis out of the residuum, the blame is perhaps not wholly theirs.

Somewhere, too, in the change from earnestness to sociability the members of given groups began rooming together: in college after college there followed first the renting, then the purchase of a home for the particular accommodation of the brethren. Presently the group of twenty to thirty men was leading a large part of its existence segregated from the rest of the student body; the old time literary society had become a modern club.

It differs, however, from the club in the intimacy of personal relations which must needs exist among men who eat, sleep and pass a large part of their leisure under one roof. It is, naturally enough, this intimacy that breeds exclusiveness. A member of a fraternity in one college, further, is a member of that fraternity in all colleges in which chapters represent the parent body. The brother from Maine must be welcomed, housed and fed if he appears unexpectedly in California; hence naturally the effort to keep throughout all the chapters a similar standard for the admission of candidates.

This underlying situation discloses little that is actually alarming, yet it does contain unfortunate elements. The breaking of the student body into small cliques of men similarlv circumstanced in birth, breeding .and worldly pdssessions tends to destroy opportunity for that variety of association once recognized as a distinct advantage of college life. The substitution of social for intellectual qualifications for membership tends to create false standards of achievement in the student mind. On this latter point Dartmouth College, perhaps the least clubridden of Eastern colleges, presents some interesting statistics.

Quite possibly at no other college than Dartmouth have the dangers of overemphasizing the fraternities been more wisely foreseen and carefully guarded against by successive administrations. Certainly nowhere has the solidarity of student sentiment been less affected by segregation. Dartmouth inclines to take unto herself credit for this condition of things as resultant from the essential spirit of the place. In reality it is resultant from an unexampled location, isolated as a State of ancient Greece and teeming with a life almost as vigorous. But that has little to do with the discussion.

Up to ten years ago Dartmouth fraternities were rather loosely banded chapters of national organizations. They met weekly in rented rooms and clung with some tenacity to the tradition at least of literary exercises. About half the students were members of fraternities; about half were not. No one cared very much about the matter either way. With the growth of the college during the past decade came the establishment of new chapters and the growing student insistence upon the necessity for chapter houses. When these could no longer well be avoided the trustees of the college admitted them with the wise proviso that no chapter house should allow more than fourteen men in residence and that no house should attempt the serving of meals. With half a fraternity's membership scattered through the college dormitories and all of it compelled to forage thrice a day for food the possibility of complete segregation was felt to be well obviated.

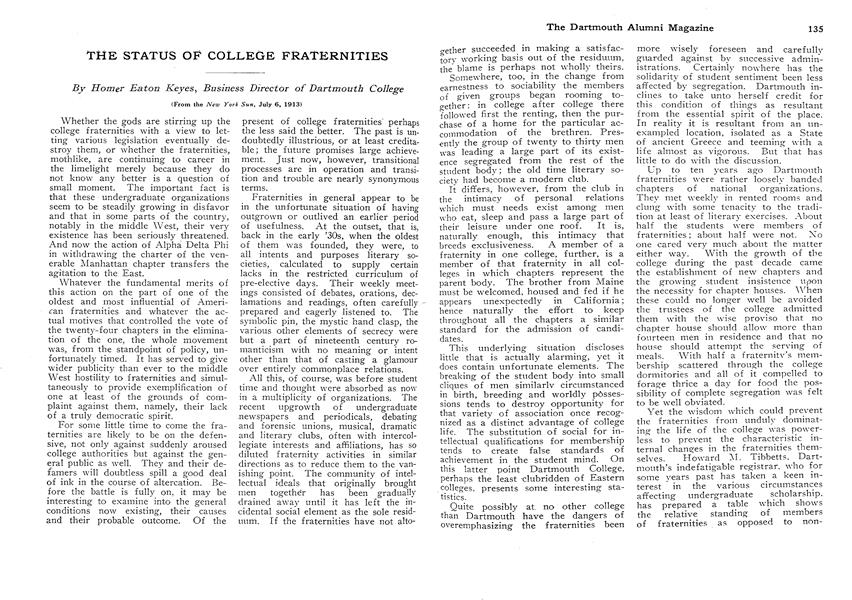

Yet the wisdom which could prevent the fraternities from unduly dominating the life of the college was powerless to prevent the characteristic internal changes in the fraternities themselves. Howard M. Tibbetts, Dartmouth's indefatigable registrar, who for some years past has taken a keen interest in the various circumstances affecting undergraduate scholarship, has prepared a table which shows the relative standing of members of fraternities as opposed to nonfraternity men at Dartmouth. The averages first given are those of the marks of all the men in each fraternity named during a series of seven semesters; the averages of all the fraternity men taken as a body, and the average of all the non-fraternity men taken as a body. About 60 per cent of Dartmouth's 1,200 are members of fraternities. A. glance at the accompanying table will show that scholastically the non-fraternity 40 per, cent lead the others consistently by a margin of several points.

Founded 1st 2nd 1st 2nd 1st 2nd 1st† at Sem. Sem. Sem. Sem. Sem. Sem. Sem. Dartmouth '09-'10 '09-'10 '10-'11 '10-'11 '11-'12 '11-'12 '12-'13 Psi Upsilon 1842 67.57 68.90 67.74 68.33 70.12 69.01 71.91 *Kappa Kappa Kappa 1842 69.52 68.83 68.45 68.99 67.82 69.52 72.40 Alpha Delta Phi 1846 66.38 66.85 69.32 66.82 68.96 68.75 70.69 Delta Kappa Epsilon 1853 70.40 69.40 68.76 65.98 63.32 67.85 71.15 Theta Delta Chi 1869 67.48 68.79 65.99 65.17 66.75 69.38 69.84 Phi Delta Theta 1884 70.73 71.55 69.25 69.67 65.12 66.74 70.63 Beta Theta Pi 1889 65.65 67.39 67.31 66.61 62.43 68.52 70.94 Sigma Chi 1893 70.52 71.23 71.17 69.70 65.02 68.33 70.31 Phi Kappa Psi 1896 67.95 67.56 70.72 69.48 69.32 69.74 74.77 Phi Gamma Delta 1901 66.53 67.34 69.63 67.53 63.90 66.08 68.25 Delta Tau Delta 1901 66.65 69.28 69.36 70.06 67.79 69.23 73.62 Chi Phi 1902 68.61 67.33 68.23 66.97 63.66 65.33 71.65 Phi Sigma Kappa 1905 67.71 68.55 69.71 67.84 63.45 65.36 66.66 Kappa Sigma 1905 69.92 70.07 71.50 70.05 70.18 71.03 72.07 Sigma Phi Epsilon 1906 74.13 74.67 70.83 72.68 68.85 71 67 72.08 Sigma Nu 1907 69.18 70.73 69.80 69.21 69.68 71.35 71.53 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 1908 71.01 71.97 70.76 72.13 66.94 68.18 67.36 Fraternity averages ....... 68.87 69.57 69.57 68.58 66.80 68.72 71.16 (about 60% of the college) Non-fraternity averages ... 73.53 73.42 73.49 72.53 68.95 71.61 74.55 (about 40% of the college)

While figures from other institutions are not available, there seems to be general agreement that, if compiled, they would show results not very different from those at Dartmouth. Certainly in no instances, save those where the non-fraternity element is so small as to be negligible, would the results be more favorable to the fraternities.

Evidently the non-fraternity men are better scholars than their fraternity contemporaries. Why this is so would perhaps be difficult to say. The defenders of the Greek letter men would attribute the difference to the fact that all the public work of student organizations, athletic and non-athletic, devolves upon fraternity men, and that the time thus expended would be quite sufficient to account for the reduced standing.

The argument is more ingenious than convincing. If the non-fraternity men have more time for study it is probably because they waste less. Fireplace gossip is a great consumer of hours. The friendships engendered and the companionships enjoyed about the glowing log may well enough compensate for the few points lost in scholarship; if so. the fact will bear honest statement.

One could hardly pursue the status of the fraternities much further without encountering the question as to why they should be allowed to exist. If, as seems fairly evident, their tendency is to interfere with the democratic solidarity of student life and to prevent the best scholastic achievement of their members, would it not be for the general good to do away with them at once and for all time?

And the answer, curiously, is in the negative, decidedly in the negative. Quite likely the fraternities need to be frightened nearly to death; but complete execution would be far from advisable. Reasons are plentiful.

In the first place it must be borne in mind that the elimination of fraternities would by no means eliminate the tendency of like to associate with like. Surely nothing is to be gained by the attempt to enforce a sort of social and intellectual gregariousness under the impression that it is one with democracy. The college secret societies have no secrets to amount to anything; but most of them have worthy traditions. Far better that they should continue to exist in the open, even in a state of vacuous inutility than that they should be destroyed, only to give way to furtive organizations, actually secret because condemned to concealment.

But inutility is not an unavoidable condition. The fraternities of America have millions of dollars invested in real estate. That investment is the best of hostages for good behavior. If in the past proper pledges have not been exacted and right standards of conduct applied, the fault lies more with the alumni of the fraternities and with the college authorities themselves than with the callow youths, whose juvenile indiscretions and immature judgments have aroused most of the present censure.

The validity of. this statement finds support in the constantly tightening hand of central councils of alumni, the increasingly frequent visits of travelling secretaries and the ever sharpened scrutiny of the internal affairs of all active chapters. This toning process is already beginning to produce results. An examination of the Dartmouth figures shows a gradual change for the better in the scholarship of the older fraternities, whose attitude, in the long run really sets the standard for the others. Aged Psi Upsilon is beginning to bestir itself; D. K. E. and Alpha Delta Phi are looking anxiously into their situation. Here again what is true of one college is probably true of others. It should, however, be observed that the fraternity interest in scholarship has not yet prompted the honoring of men solely because of high grades. Instead it has stimulated the forcing of men, chosen on other grounds, to seek scholastic in addition to other honors.

This attitude may not be altogether ideal but it is perfectly natural. He who expects the average healthy boy of from 18 to 21 to look upon scholarship as an end rather than a means is likely to suffer long and merited disappointment.

If properly used, the fraternities afford units of great potential values in the conduct of student government. Happy the college president who has learned that he can settle a question of student policy for more than half the college by threshing it out with a select delegation representing each of the fraternities!

The literary function of the Greek letter societies has passed probably beyond recall, but there is other work for them yet to do in the moulding and holding of college opinion. Destroy the easily accessible units which the fraternities constitute and the task of college discipline would be multiplied a thousandfold.

*Local. †This semester includes no marks of freshmen, thus accounting for the more favorable showing.

Homer Eaton Keyes, Business Director of Dartmouth College(From the New York Sun, July 6, 1913)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesFRANK S. BLACK

February 1914 By WILBUR H. POWERS '75 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1914 -

Article

ArticleThe football schedule, long awaited,

February 1914 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

February 1914 -

Article

ArticleNEW QUARTERS FOR THE BANK

February 1914 -

Article

ArticleTHE STATE OF THE COLLEGE IN 1780

February 1914 By Silvanus Ripley

Homer Eaton Keyes

-

Article

ArticleThe annual Harvard-Dartmouth

By HOMER EATON KEYES -

Article

ArticleCOUNCIL NOTICE CONCERNING ALUMNI TRUSTEE

February 1917 By HOMER EATON KEYES -

Article

ArticleNOMINATION FOR ALUMNI TRUSTEE

February 1918 By HOMER EATON KEYES -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S CHIEF ENGINEER RESIGNS

March 1919 By HOMER EATON KEYES -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE ALUMNI

July 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES

Article

-

Article

ArticleSOCCER

November 1920 -

Article

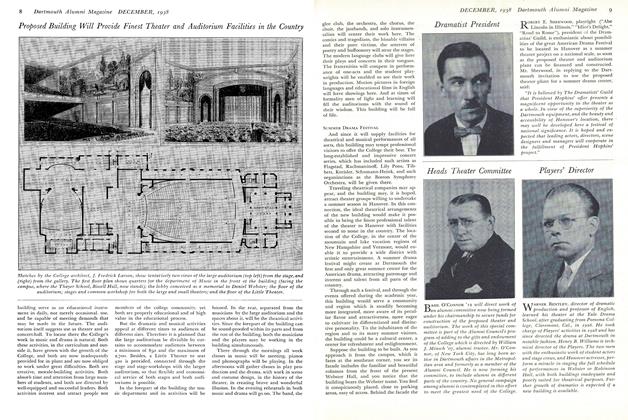

ArticleDramatist President

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Overseers

May 1951 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleOther Sports

November 1957 By CUFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

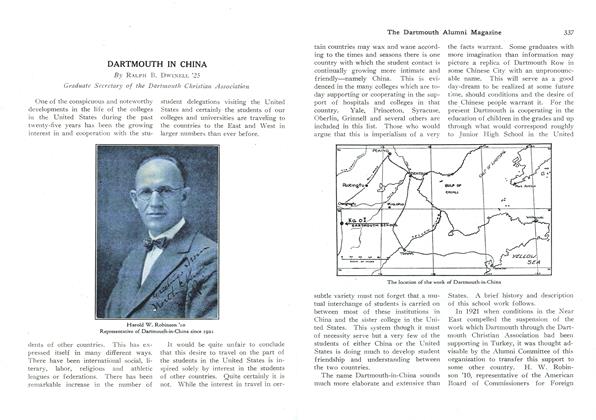

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN CHINA

FEBRUARY, 1927 By Ralph B. Dwinell '25