This article is written, in large measure, as a general answer to comments and inquiries coming to the Administration of the College, at various times, which, if put into the form of definite questions might be stated as follows: (1) What Committee has responsibility for the administration of disciplinary action for scholarship delinquency? (2) What are the rules laid down as a basis for such action? (3) What are the reasons for the rules ?

The first question can be answered briefly by stating that the Faculty has placed the responsibility for the disciplinary action in question in the hands of the Committee on Administration. This Committee is composed of the four Class Officers and a member at large, alb of whom are appointed by the Faculty, while the President and Dean of the College are members ex officio.

Before taking up the second question it will be necessary to offer a word of explanation. Each student normally carries fifteen hours work per week, i.e., in general, five three-hour courses. These hours are called "semester hours." All reference, therefore, to the amount of work failed or passed will be in terms of semester hours.

The rules referred to in the second question, as far as I am aware, have never been put into writing. They have been evolved by usage and precedent and are as follows :-

Any student, not already on probation, failing in six semester hours, in a given semester, is placed on probation, or failing in at least nine semester hours is separated from college. If a student is already on probation and fails in six or more semester hours he is separated from college. In all cases of separation, re-admission, on probation, is granted upon petition after an absence of one semester, provided the petitioner can show to the Committee that during his absence he has done something worth while and done it well; if, after this second trial, however, the man fails to meet the minimum scholastic requirement of the college he is separated a second time and a petition for re-admission is not considered.

In answer to the third query, "What are the reasons for the rules?" it will be noted that any justifiable rules must rest on the broadest recognition of the highest welfare of all the interests concerned—the college as a unit, the parent, and the "student himself. It would seem to be self-evident that the Institution which keeps upon its rolls men who, for any reason, find it impossible to meet a fair minimum requirement, or allows the father's money or the student's time to be worse than wasted, is falling far short of its threefold duty.

But to speak more specifically of the grounds upon which the rules mentioned, above are based: The first, and the most important reason was found in a statistical and historical study made by Mr. Tibbetts, the Registrar of the College, a few years ago, by which it was found that students who during the early part of their course had failed in six or nine semester hours, but were allowed to continue in college, in almost every case failed to graduate; in other words, after a halting and aimless residence at the college for four, five or six semesters they would leave for very shame, or of necessity be separated from college by the Committee. It was found that with rarely an exception the men failing in even six semester hours did not graduate, yet it was felt that they ought to have a second chance, without a break in their work, and so they were placed on probation to prove their fitness to remain in college. On these incontrovertible facts the Committee decided that, in all probability, a severe jolt early in tile course would result in the eventual success of many men who otherwise would fail miserably. It might be added that the experience of the past few years tends strongly to justify this judgment.

Further, it was felt that the retarding effect upon the college of a group of inefficients, who either could not or would not do a reasonable grade of work, was so detrimental to the general welfare that no reasonable excuse for their retention could be offered.

Lastly, if the college is to inculcate habits of industry and a proper sense of responsibility in the student body, it was felt that justice both to the parent and the student demands that time and money should not be wasted, and that lax and lazy habits must unfailingly lead to action by the Committee, which would surely teach that neglect, carelessness and inefficiency, "verily have their reward."

To this simple and brief statement of policy, we ought to add that every instrumentality that we can command, is directed toward helpful guidance and preventive measures so that none but the persistently neglectful shall fail—Class Officers, Y. M. C. A. gratuitous tutoring bureau, Faculty Advisors, the interest of Fraternities and other upper classmen, and the Administration Offices all combine to offer the fullest aids and incentives to high grade work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhen a good looking, well dressed, well mannered young man

December 1914 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1914 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1914 -

Article

ArticleA NOTABLE GIFT TO THE LIBRARY

December 1914 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1914 -

Article

ArticleMR. STREETER'S ADDRESS

December 1914

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH

OCTOBER, 1907 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Changes

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Portrait 1952

December 1951 -

Article

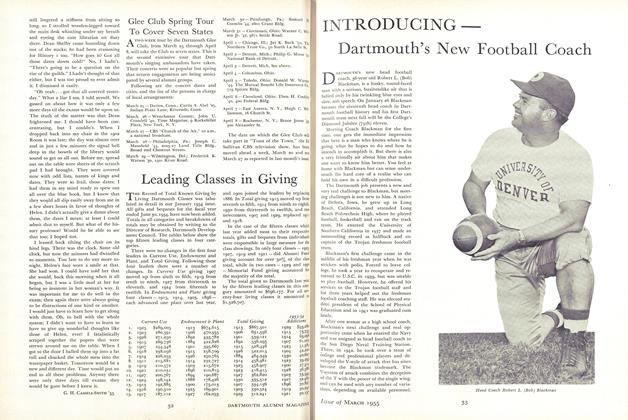

ArticleINTRODUCING – Dartmouth's New Football Coach

March 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleA New Gap Generation

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By Gayne Kalustian ’17 -

Article

ArticleWINTER SPORTS COMPETITIONS

JANUARY 1932 By S. B. Dunn '34