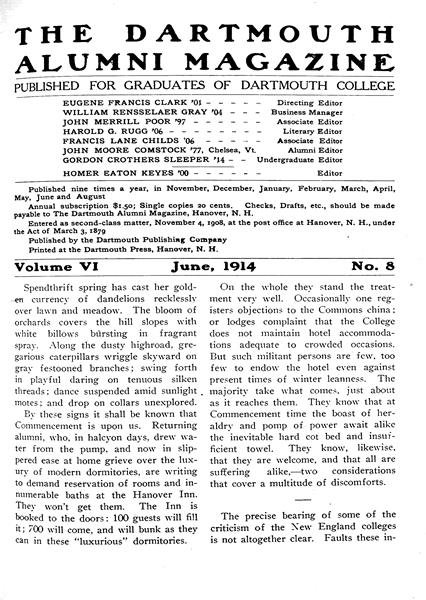

currency of dandelions recklesslyover lawn and meadow. The bloom of orchards covers the hill slopes with white billows bursting in fragrant spray. Along the dusty highroad, gregarious caterpillars wriggle skyward on gray festooned branches; swing forth in playful daring on tenuous silken threads; dance suspended amid sunlight motes; and drop on collars unexplored.

By these signs it shall be known that Commencement is upon us. Returning alumni, who, in halcyon days, drew water from the pump, and now in slippered ease at home grieve over the luxury of modern dormitories, are writing to demand reservation of rooms ana innumerable baths at the Hanover Inn. They won't get them. The Inn is booked to the doors: 100 guests will fill it; 700 will come, and will bunk as they can in these "luxurious" dormitories.

On the whole they stand the treatment very well. Occasionally one registers objections to the Commons china; or lodges complaint that the College does not maintain hotel accommodations adequate to crowded occasions. But such militant persons are few, too few to endow the hotel even against present times of winter leanness. The majority take what comes, just about as it reaches them. They know that at Commencement time the boast of heraldry and pomp of' power await alike the inevitable hard cot bed and insufficient twel. They know, likewise, that they are welcome, and that all are suffering alike,—two considerations that cover a multitude of discomforts.

The precise bearing of some of the criticism of the New England colleges is not altogether clear. Faults these institutions doubtless have; yet there is reason for pride in the thought that the great majority of them are colleges in fact as well as in name. Their tendency toward standardization as a means of securing results and judging their quality has brought forth the accusation of ultra-conservatism; and that, of course, in this experimental age, ventilated so largely with winds blowing from the west, is pretty serious.

Still, if conservatism too often insists upon realities, progressivism is as often satisfied with semblances. If the following editorial from the New YorkPost for May 23 is to be trusted, New England has much to be thankful for in her colleges, and the west has something to learn from the east in matters of higher education.

Says The Post:

It has become somewhat the fashion to look upon New England as the home of the past, left behind in the race by the Middle West, the Pacific Coast, and other enterprising portions of the country. But in one respect the land of the Pilgrim's pride continues to hold its supremacy: even the Carnegie Foundation does it honor in the matter of educational honesty. Of the 24,439 students in its colleges, 23,041 are conceded by the Foundation to be of college rank. This close approach of appearance to reality is not elsewhere duplicated. In the whole country there are only 183,089 students of college rank among the 330,832 enrolled as such; and in so old a commonwealth as Pennsylvania the students of college rank are only 13,279 among 23,633 so enrolled. New England colleges, proudly remarks a Boston newspaper, do not say, as does the lowa Teachers' College, that they 'have never refused admission to any one who applied'. On the contrary, they are what they profess to be, institutions of learning for boys and girls who have had an education in secondary schools. And it might be added that they were so, lone before the cry for 'efficiency' began to be heard.

During Prom Week, three undergraduates published an anonymous paper entitled The Yellow Journal. The product of a mistaken idea of humor coupled with cheap cupidity, The Journal was a vulgar, almost libellous, sheet. While it attacked the faculty community, it constituted a serious disgrace to the student body from which it had emanated. To the credit of the latter group, Palaeopitus took action in its behalf and recommended to the committeen on administration that the offenders be punished. The recommendation was accepted precisely as given; two men were suspended; and one placed on probation. Of course, whether or not Palaeopitus had acted, discipline would have been meted out. The significant feature of the proceeding is the acceptance by undergraduates of the principle of "their common responsibility for the public acts of individuals. It is the one notable advance in the direction of real self (government which undergraduate annals at Dartmouth or elsewhere Lave recorded for years.

For nearly a month, a corps of tree surgeons has been at work upon the campus trees, performing operations, major and minor, lopping off limbs, and, with chisel and mallet, burrowing into trunks whose depths harbored unobserved disease. The campus has been strewn with withered witnesses to the necessity for the; work. But, when it is done, the trees will have rained a new lease of life, and Dartmouth's best decoration will have been, for a little while, preserved.

The present undertaking has been accomplished under a trustee appropriation of $1000 from general funds. This sum will take care, for this year, of the trees in the College yard and immediately about the campus. In addition, a small amount of planting has been done in the vicinity of Massachusetts Row, which rises somewhat starkly behind the dignified trio of buildings which Parkhurst, Tuck, and Robinson Halls now constitute.

The full requirements of the situation will not by any means be met by this year's appropriation. There are trees other than those in the yard and about the campus; and there are bare spots other than those about Massachusetts Hall. One could find no less than four sequestered quadrangles, capable of charming treatment with gravel paths, trees, shrubs, and, here and there, a stone bench. It" is scarcely within the province of the trustees to expend maintenance funds upon such bits of garden decoration; yet the expense in each case would be but a very few hundred dollars. Here, then, is opportunity for individual expression on the part of any whose particular interest lies in the outward appearance of things.

To what extent the College, granting its ability, should go beyond the care of trees, and undertake easing the severe edges of its buildings by shrub plantations is something of a question. Shrubs, well cared for, are a source of joy. Allowed to follow the dictates of their own consciences, they become catch-alls for waste paper, dead leaves, and other debris. They shoot gaunt, unsymmetrical branches in unsightly directions. They are fuzzy at the head and scrawny at the feet. They consort with piratical insects that fatten upon them, steal their verdant garments, and leave them in wretched nakedness near to death. That is part of the case against shrubs. The case for them is being more and more frequently stated by residents and visitors. But if the pro-shrubbers ever win their case, they must prepare to back their convictions with a gardener.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

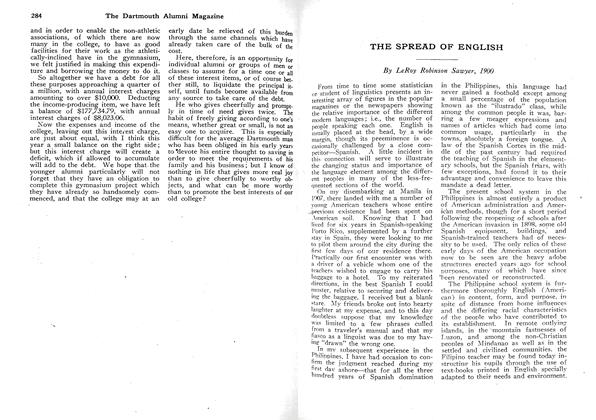

ArticleTHE SPREAD OF ENGLISH

June 1914 By LeRoy Robinson Sawyer -

Article

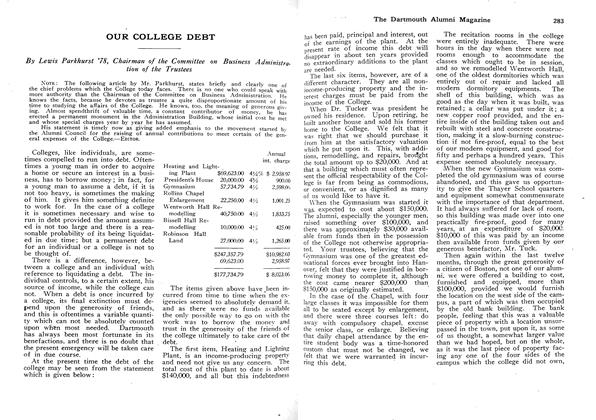

ArticleOUR COLLEGE DEBT

June 1914 By Lewis Parkhurst '78 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1914 -

Article

ArticleTHE AMERICAN JAPANESE PROBLEM

June 1914 By Sidney L. Gulick, C. H. H. -

Article

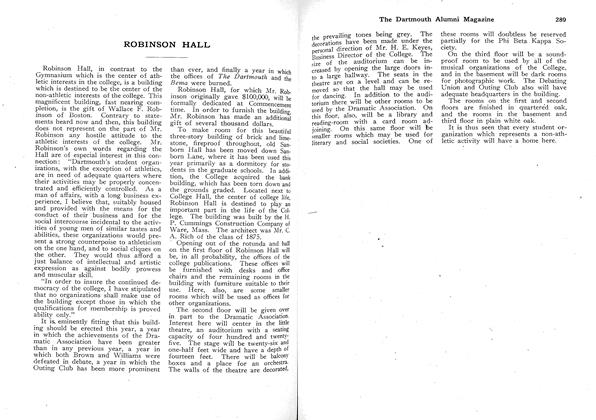

ArticleROBINSON HALL

June 1914 -

Article

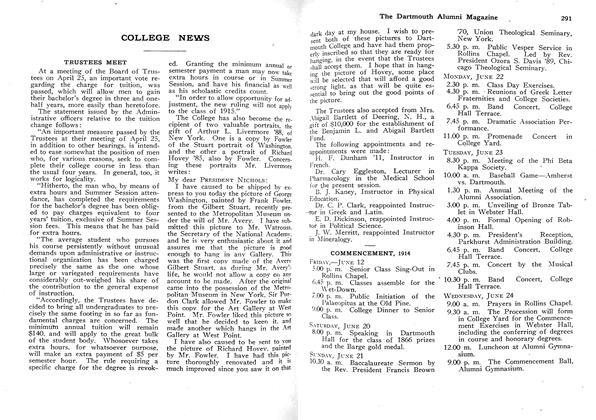

ArticleTRUSTEES MEET

June 1914