Simultaneously with the receipt of this article news of its author was received from Mr. Edward Tuck of Paris in a letter to Mr. B. A. Kimball of Concord. Mr. Tuck writes as follows: "The wounded are arriving here in large numbers now. Last night we had two ambulances and our limousine at a railway station near Versailles, under Burke's supervision, meeting a train of wounded, of whom ten were brought to our hospital, arriving about one o'clock. Tonight we send to the railway station at St. Germain to get some more, which will fill us up. 1400 English have arrived at the English Hospital established in the Hotel Trianon at Versailles, among them Judge Tuck's son Alec, who graduated you remember at Dartmouth last year. He enlisted in the "King's Own Scottish Borderers" and is a Second Lieutenant in charge of two machine guns with sixteen men. His company were among the first to leave their trenches, almost a forlorn hope, and to attack the Germans, being ordered to capture Hill 70, which is ten or twelve miles north of Arras. Three-quarters of the first line were mowed down, the second line suffered nearly as much, but the third line went by and over the others into the German trenches and on to the Hill. Alec Tuck was shot down within ten minutes of leaving the trench with a bullet through the hand and another one which skimmed across the chest and lodged in the papers of his breast pocketbook. It was a close call and he was very lucky to have escaped so easily for the most of his men and fellow officers were killed or severely wounded, the Judge and his family are staying with us now at Vert-Mont, and by a happy coincidence Alec was brought to Versailles instead of being sent to the coast, so that they can see him daily."

At the opening of the war I was at Oxford, taking some lectures to complete my course for the Bachelor of Arts degree which was later given to me by Dartmouth College. In the midst of all the European excitement it did- not take me long to decide that I would like to join one of the Allied Armies. I tried at first to join the Foreign Legion in France, with little success or encouragement. After this I joined the University and Public School Battalions, which were known as the 18th to the 21st Royal Fusiliers. These battalions were made up of men from the great public schools and universities of England. It was not long before the mistake of inaugurating these battalions was realized. With the large armies that England would have to raise it soon became apparent that these men should be trained as officers rather than private soldiers, with the result that shortly after the formation of these Battalions men with any military experience whatsoever applied for and received Commissions to the battalions of the new armies. Being an American, I had a great deal of difficulty in taking a Commission, until finally I ran across a Battalion whose senior Officers knew my people when the battalion was stationed in Egypt. This Battalion was the 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers. I was given my Commission in this regiment as a Second Lieutenant in January, 1915. I had learned the rudiments of battalion and company drill while I was in the ranks, which stood me in good stead in this new unit.

Our Camp was very near Aldershot, and we spent six weeks doing our musketry course on the most desolate range and in the most awful weather I have ever seen. From here we moved to Winchester, where we went into billets. We enjoyed our stay of six weeks here a great deal. It is one of the prettiest towns imaginable, with its glorious cathedral and the beautiful surrounding country. It was in this country, in the very early spring, that we did most of our field manoeuvres. At the end of six weeks we moved to a camp on Salisbury Plain, which had recently been evacuated by the Canadians. Here we went into tents for the first time, and the life in this bracing air had a beneficial effect on the health of the men. After a month in this camp we moved to Draycott Camp, near Swindon, in Wiltshire. Here we fired our second musketry course. By this time I had been made one of the two Machine-Gun Officers which each Battalion has, and we did our machinegun training on the same range as the men used for their musketry.

After we had been here about two months, the men were plainly showing signs of staleness, and we were feeling rather discouraged at not having been sent out sooner. Early in July rumours started flying about our departure for the Continent. Shortly after this we' were reviewed by the King as a Division, and then we realized that the rumours were no doubt true. Sure enough, on the evening of the Sth we received our mobilization orders, and on the 10th of July we entrained for Folkestone, and sailed that same night for Boulogne. An hour after our arrival in this town we were asleep in our tents in a rest camp, so well were all the details of our disembarkation arranged.

The following night, at 2 o'clock, we marched four miles to Pont-les-Briques, where we once more entrained for the Front. We arrived the following morning at Audruicq. A very short march brought us to Ostove, where we spent four days. We found ourselves here in the middle of the cherry season, which was a source of great pleasure to the men as nowhere else are there to be found such wonderful cherries as in this part of the country. The weather all this time continued to be excellent. From here we started a long trek which roughly speaking was parallel to the fighting line. It led us through Zutquerque Lambres, St. Omer, Aire, Lillers, and finally to Allouagne. This was a distance of about 60 miles, accomplished in three and a half days' marching. We had a great deal of trouble with the men's feet, as the ammunition boots with which they had been served out just before leaving England had not been worn long enough. After a few days at Allouagne, Major Gordon Forbes, C.M.G., D.S.0., Lieutenant Scott, known in the regiment as "Wee" Scott because his father had been in the regiment with us in England and who was the other machine-gun Officer, and myself were sent up to the trenches on a tour of instruction. These tours were locally known as "Cook's Tours." Unfortunately, on the second day of this trip, Major Forbes, our Second in Command, was killed by a stray shell. When we returned to the regiment we found that the Colonel, who had been working very hard in the last few months, was seriously ill and had been sent off to the base. In addition to this our Brigadier had had a bad fall from his horse and had also been sent down country with concussion. Luckily we had a very efficient Third in Command to take charge of us. In the meantime during these mishaps the Companies had been sent up to the trenches as half companies on tours of instruction.

Soon after this we marched off to take our regular place in the fighting line, or rather fighting trenches. The stays in the trenches varied anywhere from two to eight days, which were usually followed by two or four days in rest billets, and in this way we spent our summer, with very little excitement after the novelty of the life had worn off. And then it was noised about that a great attack was impending. The details came to us, but unfortunately the attack was postponed. Finally we were told that it was to take place on the 25th of September. It was preceded by four days and four nights heavy bombardment. This was to break up the enemy's barbed wire, and was to be followed by a forty-minute gas attack. On the night; of the 24th we took our places in the 'trenches, relieving an outgoing battalion. Our objectives had been given to us as follows: Our Brigade was to attack to the left of Loos, taking a half right wheel and finally to take Hill 70. The next Brigade on our right had the village of Loos itself to invest, and the third Brigade of the Division was to support these two attacks. Of course this is a very small part of the general attack, but it was what concerned us most. One's idea of an attack and an attack itself are two very different things. After a good meal in an interesting restaurant with a good orchestra playing, one often feels very capable. Annihilating a company of Germans seems a very small thing; —at least that is the way I have often felt. But the attack itself is a very different thing. Let me give you the details. We did not take our places in the trenches until about midnight of the 24th. The rest of that night was spent in dealing out the next morning's rations and in filling the new machine-gun magazines which we had just drawn from the ordnance. All through the night there was a steady drizzle, and then a hopeless grey dawn broke upon us, everyone wet through by this time and feeling like anything but an attack. The scanty breakfast .was quickly served out and consumed. For this great attack the breakfast included an ounce and a half of run for each man. This allowance of rum varies both as to its frequency of issue and amount, and is usually put in the men's tea, to keep them from hoarding it up and making an occasion of its consumption at the end of the month. That morning it was given to us neat, and well we needed it. At 5.40 we started our gas, and huge gusts of this yellowish green vapour started drifting towards the enemy trenches. Our Battalion had been given the honor of leading the attack on Hill 70 and we were to be the first out of the trenches. No sooner had our gas started than a veritable hail of German machine-gun fire could be heard on the parapet of our trench. By this time the Germans could no longer see our trenches, but having previously fixed their guns on our trench parapets their fire was only too accurate. At the same time their guns started bursting shrapnel over us with equal accuracy. Words of mine could never describe the noise and din of all this firing. All we knew was that at the end of forty minutes we were to leave our trenches and start our attack. Our watches had been synchronized the night before with those of the Engineers who were controlling the gas. Then orders started coming down the trenches. "Fix bayonets" was the first order, and this was hastily and willingly complied with. Then the cry came down: "Remember the 25th," for this was the number of our regiment as it was known in the old days. The next order came: "Put on gas helmets," and then we knew that only a few minutes separated us from the comparative safety of our trench and the veritable sheet of lead outside. The air by this time reeked of a sickening sweet smell of high explosive and shrapnel shells and the atmosphere was even _ more clouded by the faint smoke of these. It had been prearranged that as we left our trenches automatically our artillery was to lift its curtain of fire from the German first line trenches to their second, and as we advanced to their third, and so on, time limits being given for these movements. As the 40th minute ticked itself into eternity orders were given and the men climbed up on the fire steps and over the parapet. We threw our heavy tripods over the parapet, passing the guns and magazines after them, and straightened out our line so as to resemble the formation of the infantry as much as possible. I had not advanced more than forty yards when a shell burst over us, the concussion of which as well as the fragments knocked men all around me to the ground. At the same time as I fell I felt a blow in my hand and chest. What followed directly after this is very hazy in my mind, and what concerns the advance of the regiment has been told me since. I found later that I had been shot through the right hand and a flesh wound in the left breast. I got up working more as a machine than myself before I stumbled and fell again thirty yards further on. Our machine-gun team only went on and I learned later that this team was knocked out two minutes afterwards. I remember vaguely crawling into a shell hole and from there being helped into the head of a sap by a stretcher-bearer. These saps are short trenches that run out from the main trench at right angles and are used as listening posts. Here a stretcher bearer gave me a first field dressing, and later I found my way to Quality Street, which was the name given to a very small mining village which was being used as a small base for the attack of these two Brigades. Here was a scene which none who saw it could ever forget. The great majority of the men here had already been brought back from the two Brigades in front, most of the men being kilted as the Brigade on our right was the Highland Brigade. The street was covered with men lying on the pavements or just sitting wherever they found room; other men lying on the coal trucks, whose upper frame work had been so changed as to hold three stretchers. Here dressings were being applied to the most serious cases. The street literally ran red with hot fresh blood, and although half a dozen shells would have wiped out the lot the enemy were too busy with our advancing infantry to bother about this place And so we were passed on in motor ambulances to various casualty clearing stations, until we reached one about five miles behind the lines. Here we remained all afternoon until the large motor ambulance convoy started that night for Lapuygnoir. Here we were put in the Red Cross train, consisting of twenty-eight carriages of sitting and lying cases and we started our trip down country.

When we reached Abbeville, which is very near Boulogne, we were told that our destination was Versailles. This was very much to my liking, because I happened to know that the morning of the attack my people had left England to stay with their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck, on their way through to Egypt, at the Chateau de Vert-Mont, which was only twenty minutes by motor from Versailles. We reached the Hospital at Versailles, which had formerly been the Hotel Trianon, a very comfortable and luxurious sort of place. The next morning I saw my people, a very lucky coincidence as it was more than likely that we should have been sent straight through to England and a few days later my family would have been on their way to Egypt. It was here that we first learned the price the regiment had paid. The official casualties in officers out of the twenty who went to the attack, were 14 killed or died of wounds, five wounded and one alone came- through untouched. Yesterday I went to the funeral of our Colonel who had died of his wounds in the same hospital at Versailles, a very gallant soldier, who had returned to his regiment after having been retired four years and had been given the command of this new Battalion. Out of 1000 peace loving citizens in a few months he had made a perfect machine. After I fell I remember seeing lines of Khaki advancing towards the German trenches which were then invisible on account of the gas, and later I realized how great had been the work of our Colonel and how successful it had all proved. He was buried with full military honors, accompanied by 200 Cuirassiers and a small detachment of English troops from the hospital. I have learned that one of our pipers has been recommended for the V.C. His gallantry consisted in walking up and down the parapet after the hail of bullets had started and piping his men to the attack.

In a few days I return to the base, from which place I will be sent up to what is left of the regiment, which is now refitting behind the line. New draughts of officers and men are arriving shortly. The casualties in the ranks we do not know officially as yet, but they must number well over 500 men out of a thousand, as the casualties in the Brigade, consisting of four Battalions were 2000 out of 3500. The Officer casualties in the Brigade number 72 out of 80. And this was the price a Battalion paid for leading a Brigade, and a Brigade paid for leading an attack which resulted in the capture of Hill 70 and the village of Loos.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF PRESIDENT NICHOLS

December 1915 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1915 -

Books

BooksThe Bible and Universal Pease

December 1915 By B.T. MARSHALL -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1915 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

December 1915 By P.O. SKINNER -

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL—THE SECOND HALF

December 1915

Article

-

Article

ArticleLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1924 -

Article

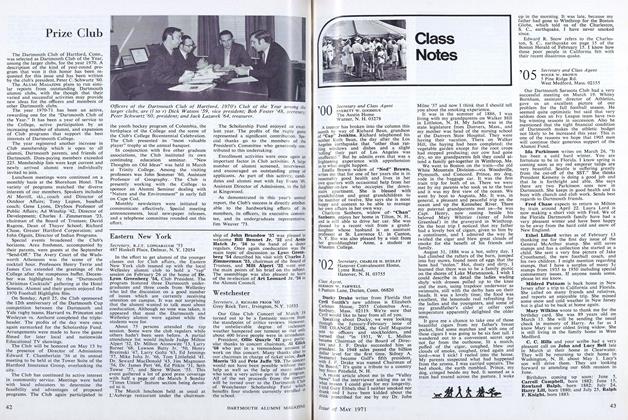

ArticlePrize Club

MAY 1971 -

Article

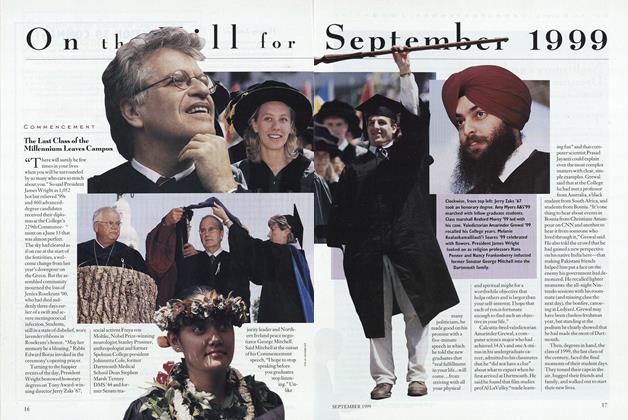

ArticleThe Last Class of the Millennium Leaves Campus

SEPTEMBER 1999 -

Article

ArticleSports Schedule

February 1962 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

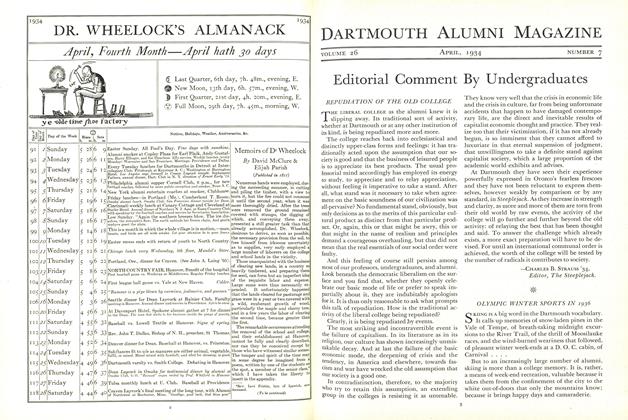

ArticleMemoirs of Dr Wheelock

April 1934 By David McClure & -

Article

ArticleStudents and Profs Seek Change

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Marley Marius ’17