Since no stream can well rise higher than its source, it is advisable not to expect impossibilities of popular government. Those who combat the democratic theory usually insist that it is folly to trust the many foolish to govern the few wise; and those who defend democracy quite reasonably assert that governments derive their just powers only from the consent of the governed, even though the governed be liable to err. On the whole, the world seems inclined in majority to follow the teachings of that philosopher who insisted that human thinking in the mass is prevailingly right.

We are dealing with a world of men-as-they-are, not with a world of men-as-they- ought-to-be. It would be hard to find a system of religion which envisaged Heaven as a republic. Universally it is depicted as a despotism—but a despotism infallibly beneficent. There are unquestionably terrestrial nations which appear to thrive best under authoritarian rule and which give a sorry account of themselves when asked to live under a democratic system. The difficulty seems to be that the benevolent despot seldom remains benevolent for very long, and owes his power less to the consent of the governed than to the fickle favor of the army, or the Praetorian Guard. It is quite true that whate'er is best administered is best—or perhaps that whate'er is least badly administered is best in the long run. After all, it is the many-headed that matter, and it. is reasonable to ask that they be the masters of their fate. Man can do little beyond the striving to make that mastery wisely effective for whatever things are of good report.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

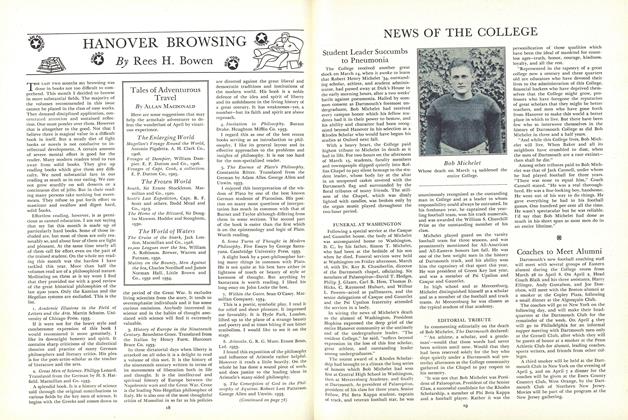

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL

August 1945 By DR. JOHN F. GILE '16 -

Article

ArticleINFANTRYMAN'S BOS WELL

August 1945 By LYNN CALLAWAY '38 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1945 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1945 By H.F.W. -

Article

ArticleMedical School

August 1945 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleThe Convenient Food

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleJust What Is "Practical"

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleMilitary Training

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleCrime Does Not Pay

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Undying

October 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe First Commandment

March 1946 By P. S. M.