The resignation of a college president is an event of importance in the educational world especially if the college is one of the first rank. For this reason President Nichols' decision to retire from his office at the close of the present college year has been chronicled in the daily press all over this country as well as in Canada. There has been also wide expression of editorial opinion and a few of these comments from representative journals are printed below. Different sections of New England are represented in the selection as well as comment from the undergraduate organs at Dartmouth and Yale.

(From the Springfield (Mass.) Union)

The news of President Nichols' resignation comes as a complete surprise both to the undergraduate and the alumni body of Dartmouth College, and by both it will be regretted. The administration of a college president usually extends over a long period, but Dr. Nichols when he leaves Dartmouth at the end of the present collegiate year to accept the newly created chair of physics at Yale will have served only seven years. They have been, however, seven profitable years for the college and afford abundant proof that the trustees acted wisely in calling upon him to carry forward the work and policies of President Tucker.

In selecting a distinguished scientist rather than a doctor of divinity the trustees made a departure from the traditions not only of Dartmouth but of most of our Eastern colleges, and their action in this respect was viewed with some misgivings. Dr. Nichols has clearly demonstrated, however, that a D.Sc. can make just as good a college president as a D.D., and in seeking his successor this knowledge will be of considerable value to the trustees. It was merely an untried theory before, whereas it is now a fact that has been practically and scientifically elucidated.

When Dr. Tucker was called to the presidency the great problem that confronted him concerned the physical condition of the college. This problem he solved with such success that literally a new Dartmouth was created, and with it a new college purpose and spirit. The small college that Daniel Webster loved became a large college, but without sacrifice of that democracy which was its greatest strength. Dr. Tucker extended the name and fame of Dartmouth, and without any thought of so doing earned for himself a place in the very front rank of college presidents. So when he was forced to resign because of ill health the trustees had not only to find a president for the college, but a man big enough to fill the place he had created.

These exacting requirements Dr. Nichols has met in a way not to disappoint any friend of the college. Under his administration the growth and prestige of the institution have increased and its activities have been multiplied. His chief aim has been to emphasize the importance of scholarship and to create higher scholastic standards, in which respect he has been singularly successful. Never before has Dartmouth occupied a better position in respect to those functions which a college is really designed to serve.

The presidency of Dartmouth, or of any other college, has never held any real attraction, however, to Dr. Nichols, who is first of all a scientist with all the passionate devotion to the cause of science that those of his mind experience. He had hoped to find time along with the discharge of his executive duties to satisfy his craving for scientific research, but the exactions of the office were too great to permit the gratification of this desire. He has accordingly chosen to relinquish the presidency and accept the more humble chair at Yale as offering exceptional opportunities in this direction. Dartmouth will be sorry to lose him and the well wishes of her sons will follow him to New Haven.

(From the Boston Herald)

The announcement of the resignation of Ernest Fox Nichols as president of Dartmouth College includes factors of unusual interest, both on the personal and on the institutional sides.

It will occasion less surprise among those who knew with what sacrifice of personal preferences Dr. Nichols took, up administrative work than with those who have known simply the gratifying results of his labors, in the increasing prestige of the college and in her material prosperity. His tastes have always been for the scholar's life. He has rare gifts as a teacher, and had won worldwide renown through his productive research work in physics while but in early life. He wishes to return to the life for which he has the greater love, and he finds in the established strength of the college the appropriate opportunity for doing this. He has given loyally and effectively his best efforts, and he will carry the genuine affection of Dartmouth men and the sincere respect of college administrators with him as he takes up his old work in physical science.

Meanwhile, the times impose heavy responsibility upon the trustees of Dartmouth to act with especial wisdom that this great college may be so led as to foresee and advance to meet the problems of the years to come—years of graver import to American life, perhaps, than any which have gone before. The need is going to lie for leadership and leaders, and the colleges must be prepared to meet such needs, if they are to fulfil their functions at all adequately.

The historical associations of Dartmouth are with Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. But while each of these has interested itself to greater or less degree in university work, Dartmouth has chosen to remain in name and in fact a college, and to specialize on undergraduate work. Her success within this field has been such that with growth numerically—untils she stands but little behind Princeton—she has become constantly more nationalized until now students are coming in ever increasing numbers from the Mississippi valley and from beyond the Rocky mountains. There is something strikingly picturesque about the way in which this old New England college stands amid the hills of the north-country, transmitting through its life and associations the New England traditions of the nation to an always larger quota of sons of the sturdy, newer civilization of the West.

The affairs of the college which has prospered so greatly as has Dartmouth must be of interest far outside her own constituency. Her age, her history and her educational ideals, as well as her widely distributed alumni groups and her widely representative undergraduate body, make her a peculiarly distinctive representative of her type. The question as to the course to be taken by institutions of this sort, in connection with the new demands of our national life, will be somewhat answered by the choice of president which the Dartmouth trustees are now called upon to make.

(From the Manchester (N. H.) Union)

The reasons advanced by Dr. Ernest Fox Nichols for resigning the presidency of Dartmouth college to accept the chair of physics at Yale are of the loftiest and most admirable. The realm of physics, of which he ,is an acknowledged leader, has for him an irresistible lure. Its atmosphere is to him the most congenial in the world. Whereas Dartmouth college under his administration has grown and prospered commensurately with the hopes of her most sanguine sons and friends, he feels that his part of the critical task in connection with which he was called to. Hanover has been accomplished, and that "the best work it is in me to do for the college is already done." However accurate or otherwise his estimate of his own potentiality for future executive service may be, it is probably a fact that Dr. Nichols never would be content to pass his days in the consciousness that he was permanently shut out from the satisfaction of further cultivating the fascinating field of physics.

The success which has attended the six and a half years' administration of Ernest Fox Nichols as president of Dartmouth is the more significant in view of the fact that he succeeded in that position an all-around scholar of the most extraordinary executive capacity. Under the administration of Dr. William Jewett Tucker, Dartmouth had experienced along all lines a growth and development which was nothing short of marvelous. It was in the midst of this splendid progress that President Tucker, the idol of every Dartmouth man, felt compelled to ask relief from the burden of responsibility which he had so nobly and so efficiently borne. Regretfully and reluctantly, the board of trustees accepted his resignation. Their next task, far from being the simple one of merely securing a president for the college, was the crucial one of securing an executive whose incumbency should ensure continuity of the constructive progress which the institution enjoyed.

Ernest Fox Nichols was selected from a large list of available possibilities. Not many years previously he had been a member of the Dartmouth faculty. The trustees of the college saw in him the man whom they believed to possess the requisite qualifications. Events have fully vindicated their judgment. In accepting Dr. Nichols' resignation, they are entitled to the satisfaction which must be afforded them by their ability to say, in all truth: "You brought to your task at Dartmouth trained powers of analysis, coupled with the loftiest ideals of scholarship. You have thus built up in the college an educational and administrative organization adequate and harmonious. Your impress upon the student body has been in terms of wider conceptions of intellectuality."

Dr. Nichols returns to the field from which for twenty years he derived that solid satisfaction which comes to a man only with the consciousness that talent, temperament, environment and opportunity are in perfect accord; and in which, ten years ago, he was awarded the Rumford medal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In that field, if his past achievements constitute a reliable criterion, he will contribute much to the sum total of the world's specific knowledge. Yale, as the chosen base of his scientific activities, is to be congratulated. As for Dartmouth, on her trustees devolves once more the momentous business of finding a man in all respects qualified to carry on the work so splendidly inaugurated by Dr. Tucker and continued by Dr. Nichols. May they be as successful in their efforts this time as they were in 1909.

(From the Hartford (Conn.) Times)

The announcement of the resignation of President Ernest Fox Nichols of Dartmouth college, tendered that he may take up a professorship at Yale, will be bad news, undoubtedly, to the vast majority of Dartmouth men and correspondingly good news to those Yale men who know of his work at Hanover. For the last six and a half years President Nichols has been at the head of the New Hampshire institution, and, though not a Dartmouth alumnus, he has become a Dartmouth man by adoption. Among the college presidents inaugurated at leading eastern institutions during the last six years—Lowell of Harvard, Hibben of Princeton, Garfield of Williams, Meiklejohn of Amherst, and Shanklin of Wesleyan—Dartmouth's executive has held his own, and brought his college into increasing regard, both at home and abroad.

Dr. Nichols' task at Hanover was not an easy one. Although not ,one of his many degrees had been given him by Dartmouth, he entered upon his work there as the successor in the presidency of William Jewett Tucker, perhaps the greatest executive Dartmouth had ever had. The college had grown and prospered under the Tucker administration. Dr. Nichols' task was to coordinate the diverse elements that came in with that growth, and to make the prosperity accruing to the college count not only for Dartmouth undergraduates, but for others outside the academic circle as well. His success with the summer school now maintained at Hanover, to which an ever-increasing number of school-teachers and lay students flock every year, is but one example of the way in which he has tried, and with success, to enlarge the scope of his institution in rendering service beyond that of the routine instruction of its own student body.

Within the college Dr. Nichols' hand has been felt, and to advantage. President Tucker gave Dartmouth quantity in enrollment; to President Nichols, in large measure, has fallen the task of giving quality and finish to the new levies. Much increased interest in things intellectual among the sturdy youths "with the granite of New Hampshire in their muscles and their brains", has come about during the Nichols' regime. The life at Dartmouth, and the tone of the student body, has been generously richened during the last six and a half years.

(From the Cleveland Plain Dealer)

Ernest Fox Nichols, president of Dartmouth college for the past six and a half years, resigns because he feels that his work at Dartmouth is satisfactorily ended. He is forty-six years old. As president he has been exceptionally successful. His able administration has brought the college through what the trustees admit has been a critical period. His resignation is accepted with profound regret.

Dr. Nichols lays down the presidency for the purpose of accepting a mere professorship at Yale. He is a phyicist, one of the foremost in America. As college executive he could devote no time to the study he had chosen for his life work, and for which his highly specialized training had equipped him, He felt that to neglect the field in which his usefulness must be greatest would be to waste his life.

How many are there who know when their imposed task is done, especially if it chance to be a highly honorable and remunerative task? How many fully realize the work in which they may make their lives most useful and best worth living? Thoreau balked at pencil making, despite its profits and prestige; he took to raising beans and tramping the woods, because he knew that in these humble and easy occupations he would find more personal satisfaction and leave a life record of greater value. On a larger scale Dr. Nichols is following the common sense philosophy of the sage of Walden.

(From the Yale News (Written by Professor H. A. Bumstead).)

President Nichols of Dartmouth, who is coming to Yale to fill a new chair in the Academic Department, is a very able and distinguished physicist. He has made a number of important discoveries, especially in the study of radiation, that is, of light and of radiant heat. A good many years ago he perfected an instrument known as the "radiometer" for measuring very small quantities of radiant heat. By means of his "radiometer", he was the first man to measure the heat which we receive from some of the planets and fixed stars.

Together with Professor Hull of Dartmouth, he discovered and measured the pressure exerted by light, which is now thought to be a very important agent in determining the behavior of comets and meteoric dust near the sun. President Nichols has made many other experimental investigations, but these two will serve to show in a measure the nature of his achievements.

He is an excellent lecturer and is very fond of teaching. As president of Dartmouth he has shown great ability as an administrative officer. Under his administration the college has made steady progress, and he has enjoyed the high regard of the trustees, faculty, and students.

The reason for his resignation from his present post and his acceptance of the chair of physics at Yale is his strong desire to continue his scientific work, for which pursuit he has found no time during the administrative work of the Dartmouth presidency. He has been unwilling to give up study and research for the rest of his life, and for this reason he has resigned from his present post so that he might continue his experimental work and teaching.

Some years ago he delivered a lecture before the Yale Chapter of Sigma Xi on "The Pressure of Light", which, as mentioned above, was one of his discoveries.

Mr. Nichols received his Bachelor's degree from the Kansas Agricultural College. He pursued his professional study of physics for a number of years at Cornell and at the universities of Berlin and of Cambridge, and has been professor of physics at Colgate, Dartmouth, and Columbia. His scientific achievements have received marked recognition at home and in Europe. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and of other learned societies; the Rumford Medal was- awarded to him some years ago by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and several honorary degrees have been conferred upon him by colleges and universities.

As a brilliant investigator in the domain of physical research, as a teacher, and as an administrator, he presents a combination of qualities which will make him of particular service to the College and University in general.

(From The Dartmouth)

Every undergraduate and every alumnus believes in the eternity of the College. There is a remarkable stability about every tradition and every building; we all believe that each feature must remain for all time. So, when the chief executive announces the completion of his task, and his resignation to enter other fields of work, the whole College awakes with a shock to a sense that Dartmouth really does change and has changed. At once the sense of loss in the past, and the vast opportunity of the future is revealed to the College itself.

Dr. Nichols came to Dartmouth when it had barely completed the growth that trebled its numbers in a single decade. His was the problem of the business administrator—to make the College an efficient public servant by systematizing its various branches, its relations; both to the outside world, and to itself. So, with the further growth of the College in numbers from a trifle over 1100 to nearly 1500, has come a like growth in the physical resources, and more important, a broadening of policy which has increasingly emphasized Dartmouth's position as a college of the liberal arts.

That both undergraduates and alumni owe a great debt to Dr. Nichols goes without saying. From the administrative point of view, the College has assumed the smoothness of a well-oiled machine. Its constituency is constantly increasing in quality and breadth. The intra-mural activities have widened with sound policies for the future. That the President is responsible in large measure for this growth is absolutely unquestioned. The regret of the College must necessarily follow his choice,—a decision doubtless made with the fullness of wisdom, but one with the most far-reaching and as yet dimly-seen results for Dartmouth.

What will come in the future, no one can yet presage. Certainly a grave problem ' rests upon the trustees to choose the able successor of a noted educator and executive: to reconcile at once the desire of undergraduates for a great human leader,—for a man who is the living embodiment of those ideals which we have come to believe are peculiarly our own,—with the requirements of scholarship almost inherent in the position. The presidency has untold possibilities for reconstructing the entire life of the College, and to fill it adequately at Dartmouth requires more than a genius.

With the entire College, The Dartmouth will bid Dr. Nichols God-speed in his return next June to the work he loves. For the present, there is the satisfaction that his career here will not be completed for nearly a year.

(From The Bema (Dartmouth).)

At each moment in the history of every institution there is one particular thing that must be done. Sometimes it is done, and sometimes it is not. The recent history of Dartmouth College has been happy in that the necessary thing has been done. It is the glory of those two presidents whom our generation knows—one through personal contact, the other only in the fortunate results of his work—that they did, each at the necessary moment, that thing which had to be done. One has handed on, the other is about to hand on, the charge to another.

The present moment calls upon the college not for regret at the loss of able leadership, but for a consideration of how it may have able leadership in the future. And first it is to be discovered what the future needs.

The spirit of the college, the love which we have for it, the number of men who bear her name, and the things which make us so proud to be Dartmouth men—we credit joyfully to Dr. Tucker. The effective organization of that spirit, of those men, and of the many things that make up the college of to-day—we credit happily to Dr. Nichols. It would be a crude comparison, and one in details inaccurate, to liken the recent history of the college to the building of a ship. Yet the comparison might illustrate what is to be expressed.

When Dr. Tucker became its commander, the ship was a worn yet still serviceable vessel, old and somewhat out of date. The framework and the general shape were the materials with which he had to work. He assembled more material, and extended the stout ribs; he hung upon the mast-head a lantern which attracted men from all the land to his help and the service of the ship. He collected a various and precious cargo and many passengers. In short, he assembled that material which was to make the finished ship and he started the work. And then he was forced to give over his work to another.

Dr. Nichols united the materials that lay before him. He laid the boarding over the ribs, stowed in the cargo, installed an engine; and from his hands comes forth a modern vessel, ready for any journey, for any cause.

He seems to think it better and preferable to do no more. To someone else is the next task—the task of charting the course which the ship is to sail, of carrying the cargo and the passengers to the port where they should go. That task is for the next president.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleROBERT FROST

January 1916 By Francis Lane Childs, '06 -

Article

ArticleLast month THE MAGAZINE had something to say concerning the advisability

January 1916 -

Class Notes

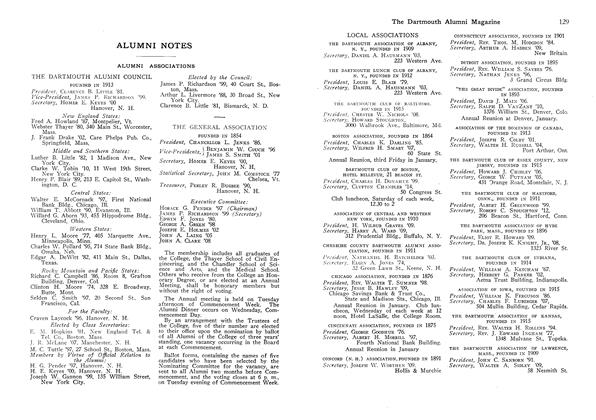

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

January 1916 -

Class Notes

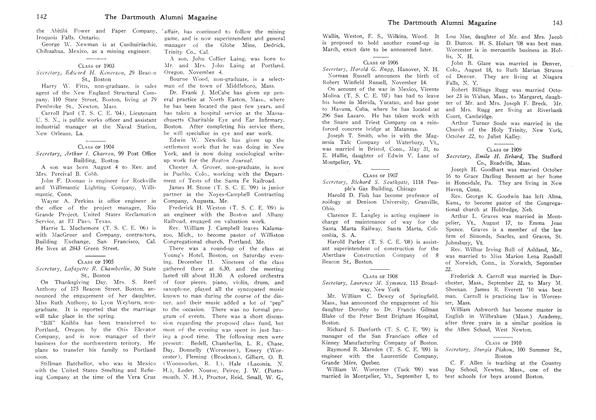

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

January 1916 By Sturgis Pishon -

Article

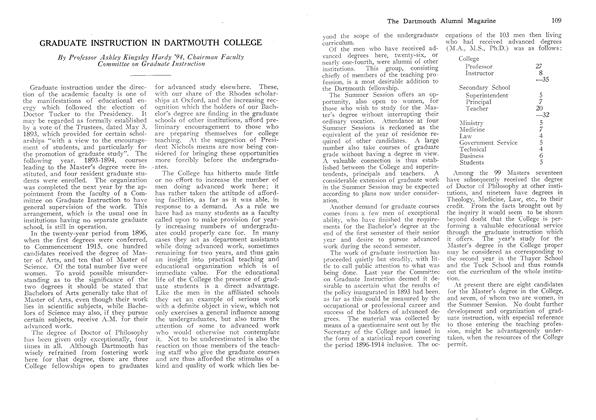

ArticleGRADUATE INSTRUCTION IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

January 1916 By Ashley Kingsley Hardy '94 -

Class Notes

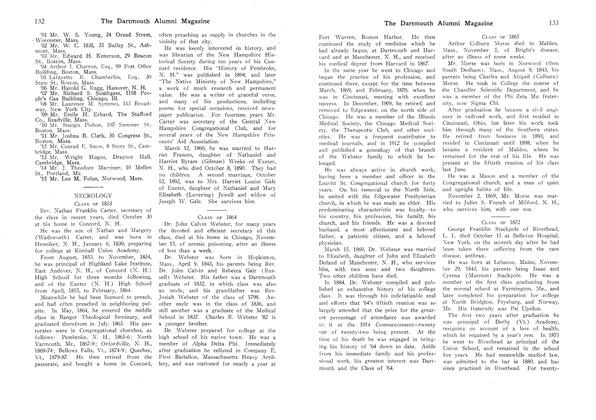

Class NotesCLASS OF 1872

January 1916