Robert Frost, the poet of New England who, by his volume, "North of Boston", has leaped in the last year from the obscurity of an unknown country school-teacher to the fame of an author widely read both in England and America, is of particular interest to Dartmouth men, because of the fact that he was for one year a student at the College. Mr. Frost was born March 26, 1875, the son of a San Francisco newspaper editor who had gone West from Lawrence, Massachusetts. His mother was Scotch. In 1886 the elder Frost died, and Robert returned with his mother to Lawrence, where he received his secondary education. In the autumn of 1892 he entered Dartmouth in the class of 1896, remaining throughout the greater part of the year, but not returning for later work. On the college records he appears as Robert Lee Frost, but he has since discarded his middle name. The years 1897-9 were spent in another attempt at collegiate education, this time at Harvard; but again college failed to appeal, and Mr. Frost turned to farming in New Hampshire. Later he served for several years as an instructor in English at Pinkerton Academy in Derry, New Hampshire; but tiring of this life, he removed in 1912 with his family a wife and four children—to England. Here in the little village of Beaconsfield near London, he settled down to a quiet literary career.

Years before, when a youth of eighteen, he had first broken into print with several poems which came out in the Independent. Most of his early work, however, still remained unpublished on his arrival in England. Soon after reaching Beaconsfield, he met and became intimately acquainted with two promising poets of the rising school Mr. William Wilfred Gibson and Mr. Lascelles Abercrombie. Under the stimulus of their friendship he published from the London press of David Nutt in 1913 a collection of poems—most of them written long before—which he called "A Boy's Will". This brought him some slight recognition, and his literary acquaintanceship spread to include such men as the late Rupert Brooke and Mr. Ezra Pound. Then homesickness seized him—a longing for the hills he had left—and under its influence his poetic genius flowered in the series of poems of New England life which he published in 1914 under the title, "North of Boston". This book at once attracted widespread attention: the London Nation among other periodicals gave three columns to a review of it. In March, 1915, it was reprinted by Henry Holt in this country, and has had a constant sale ever since in numbers that prove the American public to be far less indifferent to genuine poetry than it is supposed to be.

In the meantime, shortly after the outbreak of the European War, Mr. Frost and his family returned to America. Last spring he purchased a forty-five acre farm situated one mile from Franconia village in the White Mountains. Here he lives in a cosy little house, caring for his two cows himself, and climbing the mountains that surround his home in search of rare flowers and ferns—for he is somewhat of a scientific naturalist and very much of a nature lover. He devotes considerable time to his writing, and goes forth occasionally to lecture. Last spring he gave the Phi Beta Kappa poem at Tufts. This present month he is coming once more to Dartmouth, where under the auspices of the Arts he will deliver a lecture on poetry.

Such, in brief, has been the simple life of this poet. The part of it that is most interesting to readers of the MAGAZINE is the year spent in Hanover. I am privileged to quote from two personal letters of Mr. Frost to Mr. H. G. Rugg some details of his life here.

"I was some part of a year, lie writes, "at Hanover with the class of 1896. I lived in Wentworth (top floor, rear, side next to Dartmouth) in a room with a door that had the advantage of opening outward and so being hard for marauding sophomores to force from the outside. I had to force it once myself from the inside when I was; nailed and screwed in. My very dear friend was Preston Shirley (who was so individual that his memory should be still green with you)* and he had a door opening inward that was forced so often that it became what you might call facile and opened if you looked at it. The only way to secure it against violation was to brace it from behind with the door of the coal closet. I made common cause with Shirley and sometimes helped him hold the fort in his room till we fell out over a wooden washtub bathtub that we owned in partnership, but that I was inclined to keep for myself from the inside when I was nailed I may say that we made up afterward over kerosene. One of us ran out of oil after the stores were closed at night and so far sacrificed his pride as to ask to borrow of the other.

"I'm afraid I wasn't much of a college man in your sense of the word. I was getting past the point when I could show any great interest in any task not self-imposed. Much of what I enjoyed at Dartmouth was acting like an Indian in a college founded for Indians. I mean I liked the rushes a good deal, especially the one in which our class got the salting and afterwards fought it out with the sophomores across pews and everything (it was in the Old Chapel) with cushions and even footstools for weapons—or rather fought it to a standstill with the dust of ages we raised.

"For the rest I wrote a good deal and was off in such places as the Vale of Tempe and on the walk east of the town that I called the Five Mile Round . . . I wrote while the ashes accumulated on the floor in front of my stove door and would have gone on accumulating to the room door if my mother hadn't sent a friend a hundred miles to shovel up and clean house for me."

In a second letter Mr. Frost says: "It is strange there is so little to say for my literary life at Dartmouth. I was writing a good deal there. I have ways of knowing that I was as much preoccupied with poetry then as now. 'My Butterfly' in 'A Boy's Will' belongs to those days, though it was not published in the Independent until a year or two later (1894 or 1895, I think). So also 'Now Close the Windows' in the same book. I still like as well as anything I ever wrote the eight lines in the former beginning,

'The grey grass is scarce dappled with the snow'.

But beyond a poem or two of my own I have no distinctly literary recollections of the period that are not chiefly interesting for their unaccountability. I remember a line of Shelley's—

'Where music and moonlight and feeling are one'

quoted by Professor C. F. Richardson in a swift talk on reading, a poem on Lake Memphremagog by Smalley in the Lit, and an elegy on the death of T. W. Parsons by Hovey in the Independent. I doubt if Hovey's poem was one of his best. ... So the memory of the past resolves itself into a few bright starpoints set in darkness. (The sense of the present is diffused like daylight). Nothing of mine ever appeared in Dartmouth publications."

Of the characteristics of Mr. Frost's poetry, the present writer feels it necessary to say little, beyond advising every lover of the New England hill country and its people—and that must include all Dartmouth men—to read "North of Boston". The poems in the earlier volume, although numbering among them some pleasing lyrics of nature, are slight in comparison with the work of the later book. In "North of Boston" Mr. Frost has caught the spirit of New England life in the back country as no one else has ever done in verse. Grim, gripping, elemental—the grayer sides of human passion are here presented in an unforgettable manner. The tragedy of everyday life in lonely places, the philosophy of uneducated but deeply thoughtful men and women, the oppression of solitude, the background of the eternal hills and lakes and consciences—these are the elements which combine in Mr. Frost's work to stir our nobler emotions and to awaken our broader rroral sympathies with life. He has accomplished in verse what such writers as Miss Jewett, Mrs. Freeman, and Miss Brown have earlier done in prose. The reader feels, on putting down this volume, that he understands New England life more fully than before.

Like Wordsworth in choosing his subjects from rustic life, Mr. Frost is also like his great English master in his use of simple, elemental diction. The form of the poems is admirably suited to the matter. It represents almost the creation of a new form in English verse, but it is not the shapeless rhythms of the vers librists, nor the tom-tom music of the Salvation Army school. It is quiet, restrained, and even. Nearly all the poems in the volume are written in a modified blank' verse, which until one is accustomed to it scarcely seems to be blank verse at all. Line after line of monosyllables, with a notable deficiency of heavy stresses, and with an abundance of feminine and weak .endings, give an effect I have never met with elsewhere—an effect, however, very pleasing because of its harmony with the themes presented. The closing lines of the poem entitled "The Woodpile" is illustrative of this power to make the simplest words serve a high poetic purpose:

"I thought that only Someone who lived in turning to fresh tasks Could so far forget his handiwork on which He spent himself, the labour of his axe, And leave it there far from a useful fireplace To warm the frozen swamp as best it could With the slow smokeless burning of decay.

*Shirley died in 1905.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePRESS COMMENT ON PRESIDENT NICHOLS' RESIGNATION

January 1916 -

Article

ArticleLast month THE MAGAZINE had something to say concerning the advisability

January 1916 -

Class Notes

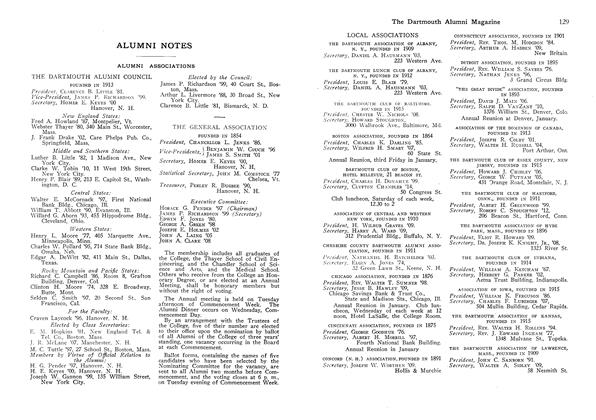

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

January 1916 -

Class Notes

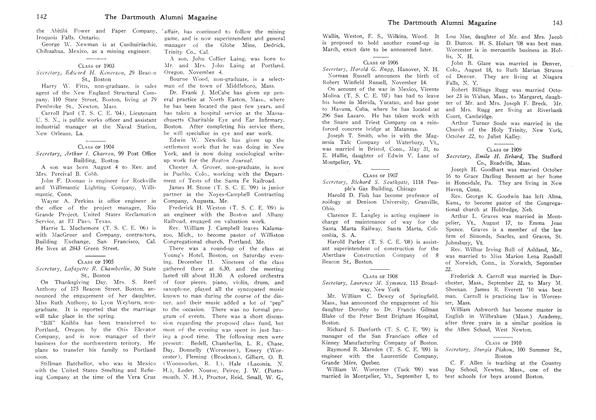

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

January 1916 By Sturgis Pishon -

Article

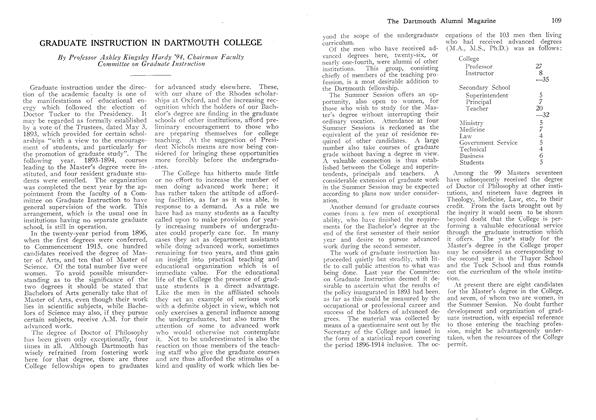

ArticleGRADUATE INSTRUCTION IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

January 1916 By Ashley Kingsley Hardy '94 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1872

January 1916

Francis Lane Childs, '06

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleHal Sandstrom '82: "instants of appreciation" in Africa

MARCH 1984 -

Article

ArticleGolf

June 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleBasketball

MARCH 1969 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTop Television Man

June 1950 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42 -

Article

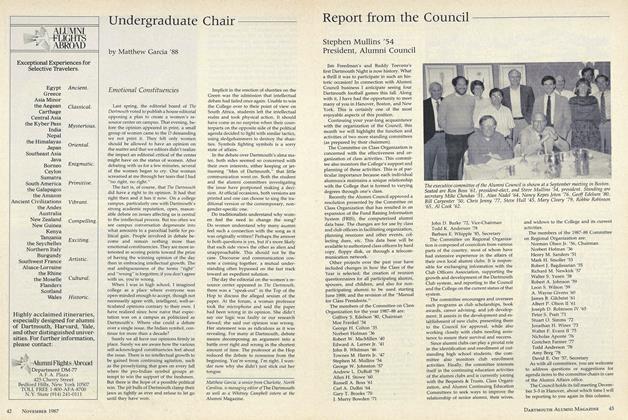

ArticleReport from the Council

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Stephen Mullins '54