These extracts from Nathan Smith's correspondence were collected by Prof. J. K. Lord in the course of research for his History of Dartmouth College. He has put them together in the following article and in this form they make a valuable addition to our knowledge of Dr. Smith in his relation to Dartmouth and Hanover. "The Life of Nathan Smith" by Emily A. Smith was reviewed in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE of November, 1914.

Among the truly eminent men who had a part in the early history of the College, Nathan Smith has a prominent place.

He had certain remarkable gifts, medical insight, the power of lucid statement, the ability to impart enthusiasm, and a genius for organization. He did not have .the missionary zeal of Eleazar Wheelock, the wide interest of Bezaleel Woodward, or the devoted altruism of Francis Brown, but he had a single aim, the advancement of medical science, that found its expression in his own extensive practice and in the organization of the three medical schools at Dartmouth, Yale, and Bowdoin.

Coming to Hanover in 1798 to organize the Medical School he continued at its head till 1813, and also gave a course of lectures in 1816. He was then frightened away by the legislative denunciation of penalties against the officers of the College and went to reside at New Haven. Among the friends whom he left at Hanover was Mills Olcott, who took charge of his affairs, and of his family, which remained in Hanover for some time before going to New Haven. I have in my possession about forty letters written by Dr. Smith to Mr. Ol-cott, mostly between 1813 and 1822, which give pleasing suggestions of the man, of which I think some extracts may be interesting.

Dr. Smith had been successful in his profession in Hanover and had acquired considerable ownership of real estate. Besides a farm in Norwich and another in Chelsea,. Vt., he owned in Hanover most of the land beginning with Professor Fletcher's present house lot and extending on both sides of the road as far as Girl Brook, and he lived in a house, not now standing, near the residence of President Nichols. The letters in question have to do largely with the care of this property and with debts, of which there were many owing to him and by him. That he was free in the use of money is shown by an extract from a letter written in May, 1818:*

"I suppose you are right as to the goad of fame, but not quite so correct about money. You [say] that if I had money it would do me no good because I should spend it. Now, I always thought that spending money was all the fun of it, as it does no good while we keep it."

In the same year he says that he has paid since leaving Hanover debts there to the amount of $1035, and thinks he can do as much more within the next year. His practice steadily increased not only in New Haven but elsewhere. In 1813 he spoke of a great "run of business" in New Haven and in 1817 he wrote: "I have done considerable business in and about Boston"; and later, in again writing from New Haven, after returning from a long absence and beginning his lectures, he said:

"I have been able to do a good deal of profitable business besides. Besides the operations today, which amounts to 100 -dollars, I have operations enough engaged to come to another hundred, so that though I have I been absent a long time have not lost any business in this place. If I had as many hands as old Briarius I could find use for them all."

And still again in 1818:

"I have of late had considerable profitable business, and as the grave digger said he. hoped by the end of that year he should make up a round number of graves that he had dug, so I hope in the course of the summer I shall be able to count a goodly number of pleasant operations which I have performed."

As time went on and his reputation spread his services were in greater demand and his fees correspondingly increased. Writing from Brunswick in 1822 he said:

"I have lately received an invitation to go to Eastport, after my course is through here. A certain man, by the name of Bates, who has more wealth than health, has sent for me with an assurance that he will pay me' what I charge. I think I shall not be bashful, but carry a stiff upper lip. From this to Eastport it is a little less than 300 miles, down east, as they call it here."

The farms in Norwich and Chelsea were sold but the property in Hanover caused more anxiety. It was in part rented to a man named Stuart, and in October 1819 Dr. Smith wrote:

"Tell Stuart that during the winter he must keep up the fences and suffer no four footed beast to tread on that ground, and if he does I shall be after him knife in hand, as soon as I issue on earth again, which will be in the spring."

A few days later another reminder showed how earnest he was:

"I hope you will touch up Stuart to keep up the fences about the home lot and not to suffer any four footed beast to tread on the sacred ground, which has been appropriated to fruit trees, as the damage will be required at his hands."

That Dr. Smith was possessed of a keen sense of humor often appears, even when he writes of business. In 1822 when Professor Adams thought of buying Dr. Smith's estate in Hanover the latter wrote:

"Tell him I should like to sell it for what it is worth. The price will be six thousand dollars, paid down in Boston money or Salem money. If I cannot sell it for that I will punish Hanover by living on it myself."

At one time one of his tenants, a very fat man, was behind with his rent. Writing to Mr. Olcott about it he said:

"He has been in the habit of paying so punctually it is strange he should fail. I thing on the whole he had better roll off of the farm, for if he gets much fater he will of necessity be buried there."

That he retained an affection for the products of Hanover, as well as for the place itself, may be inferred from a letter of October 1819:

"N.B. We .have no good cyder in this country this year and if from [name illegible] or others, who may chance to owe me, you could send me. 10 barrels by some of Lyman's boats so as to arrive in Novr. I should like it."

The conditions of the practice of medicine in New Haven at the time of Dr. Smith's moving thither, and doubtless elsewhere prevalent, as well as his own attitude are brought out in a letter of December 1813:

"Respecting our School, it is very much as I expected—the numbers who attend are not large but very respectable. I perceive there will be much for me to do if I continue here. They have in and about this place a rare sort of faculty; some are called bonesetters and some cholic doctors, some are females and others of the masculine gender Shortly after I arrived here I was consulted by a pretty young Lady. The case was a white swelling of the knee joint She very honestly told me in her relation of the case (without supposing anything wrong had been done) that she had had it set five times, twice by women and three times by male bonesetters, but instead of growing better it grew worse every time it was set.

"I am thinking that if I should conclude to take up my residence here I must have a severe conflict with this tribe of bonesetters, for I never could, when young and pliable, get on with them, and now grown old and stiff feel less inclined to yield the least approbation to those kind of gentry. How such a kind of controversy might terminate none can tell. I am told, and partly believe it, that there are many men in this state, who stand high in the estimation of the world as men of science, who have the fullest confidence in this kind of guglery."

In other things than medicine Dr. Smith avoided controversy and, in fact, it was his disinclination to it that finally took him from Hanover, as he did not wish to take part in the college struggle. In the spring of 1818 Mr. Olcott had written Dr. Smith asking advice for a young physician, named Porter, who was planning to go to Scotland for study. Dr. Smith's reply touched incidentally upon the comparative value of medical education in Europe and here, but was more earnest on the avoidance of controversy. Writing May 19, 1818, he said:

"There is little or no connection between this place and any part of Scotland, and as to Medical Books and In- struments of chemistry, surgery, &c., the Booksellers here furnish us with all new publications before the books are dry, and all our instruments are better made here than in Europe. Unless Dr. Porter has some other object in view than merely the perfecting himself m medical science, or can do something beside to benefit himself I should doubt the expediency of his proposed tour....

"I have always had a good opinion of Dr. Porter's talents, but have several times thought that I would speak to him on one subject which I have never neglected—that was his strong disposition to take a decided part in party tontroversies. Though he may espouse the right side, yet as he can have no great interest in the thing at his age, he will not be apt to be rewarded by the party he favors for all the bufferings he may sustain on their account. Young men are too apt to act from feeling on such occasions, while old men more cautiously calculate the consequences."

Another letter written about the same time shows not only how he avoided political controversies, and how contemptuously he looked down upon them, but also how controlling was the thought of his profession.

"To-day was our election. I did not attend, but am informed that toleration carried all before it. This year makes a compleat revolution throughout the state and will bring fourth a new constitution and will change nearly every officer in the Government. Whether it will be for the better or the worse I do not know and feel perfectly indifferent about it. As all these political rogues mean no good to me, why should I care for them? I go on cutting flesh and pills just the same, let who will be Governor—revolutions in government make no change in diseases nor in physicians fees."

Dr. Smith's experience with political parties in New Hampshire had not been reassuring. A hard bargain had been driven with him in connection with the erection of the medical building, and money which he had advanced was slowly and grudgingly repaid, and laws were passed in reference to dissection which led him to wish to leave the State. But the legislature of Connecticut proved no more liberal.

In May 1817 he wrote:

"The Sovereign Mob, the Legislature of Connecticut, have a bill before them which, if it passes, will put an end to our School in this place and will absolve me from my obligations to them. Like the christian of old, if they persecute me in one city I shall flee to another."

In July 1819 he added:

"Our Legislature did not quite pass the law, which was to hang all the Doctors, but they came so near to it as to strike a death blow to the Institution by the prosecutions, &c, which has led me to contemplate a removal from this place with some earnestness, but whether it will be to the east or south I am not determined."

The letters contain several references to the troubles at Hanover and indicate an irritation that anything so trivial as a controversy between the College and the University should have interfered with an important matter like the promotion of medical interests. Both parties would have been glad to retain him, but he sympathized with neither, and his references to the College party are amusing in their ill concealed disgust that any set of men could so persistently contend for a cause that had no interest for him. He was tremendously in earnest over one thing, but beyond that he did not see how men could find it worth while to antagonize one another.

In March 1818 he wrote:

"I find by the papers that the College Folks are to hang on by the gills another year. We have heard a great deal about Societies' Libraries, medical examinations, &c., since we left that land of harmony and science."

In May he wrote:

"Your confidence, I see, is good in the College case, but I expect the next Legislature in N. H. will make a law to hang all the Old Board Folks and their Attornies."

The decision of the college case he passed with the remark: "The Old Board, it seems, have succeeded in their title to the College with all appurtenances thereunto belonging," but three years later, February 28, 1822, on the accession of President Tyler, he wrote from Brunswick, Me.:

"I perceive you have at length found a president for Dartmouth. I have never seen the man and never heard much of him till I heard that he was thought of for president. He was then spoken of as a man of good talent and well qualified for the Office. I sincerely hope you may prosper with him. I cannot help thinking, seeing you have now got a president, that it would be better for the Institution if some of the Old hands in the Board of Trust should withdraw, but perhaps they feel something as those fellows did who attempted to hold up the ark in olden time, and imagine it will fall over if they let go of it.

"All this, however, is conjecture, I do not know much about Colleges, and take much less interest in them than I did. I do not think it can make such a mighty difference in the world as to who learn boys hie, hac, hoc."

In addition to his work at Yale and Bowdoin Dr. Smith lectured at the University of Vermont from 1822 to 1825. This division of his work necessitated much travelling over routes not covered by the scanty stage lines of those days, and a letter from Brunswick in April 1822 gives an illustration of how he managed his travelling in one instance, and also of the difficulties of travelling in general. He had a horse and chaise in New Haven, which he wished to have in Hanover on his going from Brunswick. His two daughters also wished to go to Hanover, and so he had asked Mr. Olcott to get some one to go to New Haven and to drive the horse and chaise to Hanover and bring the girls with him. But in this letter he wrote:

"Mrs. Smith thought the girls had better go to Hanover by stage, and that they were looking out for some one to take on the chaise, but, if the girls can get to Hanover in the stage, I shall not want the horse and shaise at Hanover, as I have procured a horse and gig here to come on with, which will convene [convenience ?] me in my mode of traveling better than the stage. I have written to Mrs. Smith these circumstances and requested her to look out for some person who was traveling that way in the stage, who would take a little care of them. They can come to Hartford in one day, stay there a day and a night, if they please with their acquaintances and from Hartford to Hanover they will be out but one night."

Three days now seem a long time for a journey from New Haven to Hanover, but it was under such conditions of travel that Dr. Smith moved from place to place and did his lecturing and professional work.

*The letters are quoted as written except in the matter of punctuation, of which they have little.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleALONG THE OUTING CLUB TRAIL ON SKIS

March 1916 By Fred H. Harris '11 -

Article

ArticleTHE FEBRUARY MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleEXHIBITION OF CORNISH ARTISTS

March 1916 By George Breed Zug -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleWhen, with the coming spring, Professor John King Lord returns

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleWINTER CARNIVAL—A NATIONAL EVENT

March 1916

Article

-

Article

ArticleA LETTER FROM DABNEY HORTON '15

July 1918 -

Article

ArticleHonor Professor Young

APRIL 1932 -

Article

Article1942 Fund Passes $75,000

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleLloyd D. Brace '25 Begins A Full Term As Alumni Trustee

July 1955 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

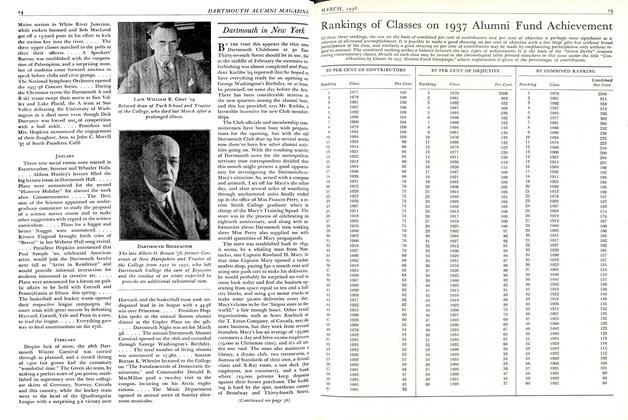

ArticleDartmouth in New York

March 1938 By Milburn McCarty '35