by James M. O'Neill '07, Craven Laycock '96, and Robert L. Scales '01, New York, 1917. The Macmillan Company. 495 pages.

Professor O'Neill states in the preface of his revised edition of Laycock and Scales's Argumentation and Debate, that "the original text contained the clearest and most orderly explanation of the subject ever published." With this statement, many teachers will find themselves in perfect accord; and they will, therefore, inquire, why any revision of such an admirable text should be attempted. Professor O'Neill's answer is, that "this text, in common with all other texts in argumentation, was not sufficiently thorough for college and university classes." At the outset, then, Professor O'Neill disclaims any attempt to correct or condense the work of his predecessors, and frankly avows his purpose, to expand the original text. That he has done this, is obvious; and to his readers is left the task of determining whether this expansion has been accomplished wisely.

Teachers, who have used the original text of Laycock and Scales, know, that the study of that text has produced many able debaters among college and university students, as well as among the students of preparatory schools. Why, then, does Professor O'Neill say, that the original text "was not sufficiently thorough?" The only answer is, that the original authors, though clear and concise in almost every portion of their work, were not exhaustive in their treatment of the subject. Their object was to make a complex subject simple; and, if they erred at all, it was in accomplishing this aim too well. What, in its nature, was truly complex, appeared to the superficial student of their work as being, in its nature, simple. Fundamentals were emphasized without undue elaboration, and unessential refinements were omitted. The text, therefore, was one, so clear, and simple, and practical, that it did not betray the multifarious background from which its principles were drawn; it did not indicate always the way in which these principles had been derived; and it may not have sufficiently emphasized the universality of the application of these principles. The problem of Professor O'Neill, then, in revising this work, was to make more apparent the real complexity of the subject, with its manifold ramifications and its universal application, without sacrificing its original clearness and orderly development.

Professor O'Neill's revision has been so thorough, that he may justly lay claim to having rewritten the whole text. In every chapter, much new material has been added, and especially is this true of the vital chapters on the proposition, the issues, evidence, argument, and fallacy. The chapters on the burden of proof, the nature of debate, the main speeches, the rebuttal speeches, and delivery, as well as the new appendix, are, perhaps, more exclusively than other parts of the work, the product of Professor O'Neill's authorship, and they contain much that is interesting, stimulating, and suggestive. The broad origin of argumentation in logic, law, rhetoric, and oratory, is everywhere made apparent.

One criticism of the revised text is inevitable, and this, the author has anticipated. It will be said, that he has drawn with a free hand from the works of other writers. He has. He admits it. He has used direct quotations most profusely, where he might have rewritten the substance of what he borrowed. This, however, should not give ground for serious adverse criticism of his work; since it gives his product a most substantial foundation in long recognized and widely known authorities. Should we not rather see in this a tribute to Professor O'Neill's frankness and modesty?

The book, as a whole, is one that restores to its subject its original complexity ; yet, by frequent summaries and partitions in the form of topic outlines, it retains and emphasizes the orderly development that characterized the original text. In its revised form, the book should satisfy the needs of both elementary and advanced classes in argumentation and debate.

The volume of Proceedings of the New Hampshire Historical Society for the years 1905-1912, which has only recently been issued, contains a very interesting address, "Dartmouth College: its Founders and Hinderers," delivered in 1906 before members of the society and the College by Franklin B. Sanborn, in which he put forth a case against those whom he called "hinderers" of the College. His iconoclastic attitude (whether it arose from his praiseworthy loyalty to his native state or from another cause) is based on the belief that the people desired such a state university as Dartmouth might have become. Eleazar Wheelock himself, said Mr. Sanborn, cannot "be excused from appearing at times as less the founder than the hinderer of Dartmouth College," because he seemed to disregard the desires of those men of the state "to whom he was specially indebted for the very existence and location of his institution." But because Webster prevented that state control through which Dartmouth would have "fallen into the strong current of state education" and had "the resources of a proud commonwealth to support its expenses and extend its influence," said Mr. Sanborn, "I therefore rank him and his associates in the great lawsuit which he so brilliantly won, as the chief hinderer of the College, of which he has been for more than a century the ornament and the pride."

Professor E. R. Groves '03 is the author of the following articles: Contribution to Symposium, "What May Socialists Do Toward Solving the Problems of the Present War Situation" and "Sociology and Psychoanalytic Psychology; an Interpretation of the Freudian Hypothesis" in the American Journal ofSociology for July, 1917; "The Rural Worker and the Country Home," in Rural Manhood for October, 1917; "The Rural Worker and the Country Schools," in Rural Manhood for November, 1917. Since February, 1917, Professor Groves has been the editor of the Rural and Community Sociologist, a department in Rural Manhood. His latest book, "Using the Resources of the Country Church," has just been issued by the Association Press.

Ben Ames Williams '10 is a regular contributor to the All Story Weekly. The following novelettes from his pen have appeared in this magazine as follows : "Swords of Wax," in the issue for July 28; "The Powder of Midas," in the issue for June 16 and the three succeeding issues; "The Golden Girl of Linkkoping," in the issue for May 26; and "Three in a Thousand," in the issue for October 20.

"The Negro Comes North," by Kings-ley Moses ex-'11, appears in the Forum for August.

H. Thompson Rich '15 is the author of Holland, Wright, Lewis & Co., Inventors and Purveyors Extraordinary to the Governments of the World in Account with Uncle Sam," in the September Forum, of "What Constitutes Treason," in the November Forum, and of "Dropping the Easy Job and Tackling the Tough One," in the October American Magazine. The issues of the Madrigal for September and October contain poems by the same author.

William Carroll Hill '02 is the author of a pamphlet of 24 pages entitled "History of the Cecilia Society, Boston, Mass., 1874-1917."

Alfred M. Hitchcock, who received his Master's degree from Dartmouth in 1896, is the author of "Over Japan Way," published by the Henry Holt Co.

Recent articles by Gabriel Farrell'll are "The Episcopal Church and the Labor Movement in the Living Church," —(I) "What the Church Has Done," July 28; (II) "What the Church Can Do," August 4; "Trinity Tower Paintings," Boston Transcript, August 25; and "The Living Church," September 8; "Four Varieties of Belief," BostonTranscript, September 19. Book reviews appearing from time to time in the Transcript, over the initials G. F. are the work of Mr. Farrell. An article appearing in the September number of The.Chronicle, entitled "Priest Impressions by One Unwed, Unhonored and Unknown," which in clever satire exposes the idiosyncrasies of parsons and parsons' wives, is attributed to Farrell.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA LETTER FROM THE FRONT

November 1917 -

Article

ArticleTHE NEED FOR UNUSUALNESS IN THE WORK OF THE COLLEGE

November 1917 By Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAmerican colleges have given so liberally of men

November 1917 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH WAR RECORD

November 1917 -

Article

ArticlePLATTSBURG-A TRIUMPH OF EFFICIENCY AND DEMOCRACY

November 1917 -

Article

ArticleAT PLATTSBURG

November 1917

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE STRANGE WOMAN

November 1941 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksAMERICAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT IN KOREA

October 1951 By John W. Masland -

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTMAS NIGHTINGALE: THREE CHRISTMAS STORIES FROM POLAND.

March 1933 By M. S -

Books

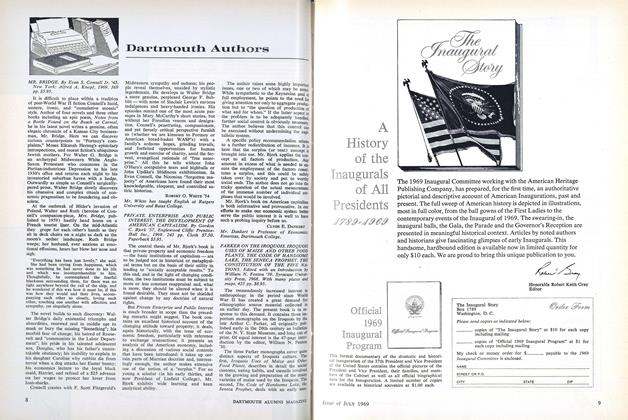

BooksPARKER ON THE IROQUOIS. IROQUOIS USES OF MAIZE AND OTHER FOOD PLANTS. THE CODE OF HANDSOME LAKE, THE SENECA PROPHET. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FIVE NATIONS.

JULY 1969 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25 -

Books

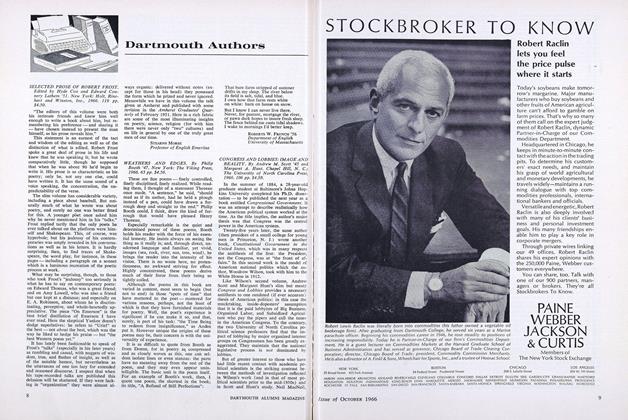

BooksWEATHERS AND EDGES.

OCTOBER 1966 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksScience In Easy Reading Books

APRIL 1929 By W. B. P.