Cecil Heacox seems that rarity among men, a happy man. And he should be. He managed to wed his deep love for fishing with a challenging and, at the time, pioneering profession in which he served sportsmen and embattled nature with equal benefit. And in The Education of an Outdoorsman he writes about his life with humor and gratitude and in graceful prose.

Ten years out of college, Heacox made in rapid succession three decisions which, in the poet's words, "made all the difference." In mid- Depression he chucked his job, said "to hell with the business world," and became a "business dropout." Weeks later, walking the hills of his native upstate New York, he concluded that "working for a cause instead of a corporation" was his road. And finally, he enrolled in Cornell Graduate School to study for his degree in aquatic biology.

Degree in hand, he was first assigned to the New York State Conservation Department where, for the exalted salary of $3.20 per day, he waded streams, rowed boats, tested water, and examined trout, inside and out. But the aquatic biologist had found his way, revelled in it, tightened his belt, and kept on wading. His next assignment was to eastern Long Island where, among other tasks, he labored to determine the sex of broadbill swordfish, wrestled on deck with a bluefin tuna before tagging it for release (a historic first in marine biology), and where he was almost blown into the Sound by the long- remembered devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938.

During the almost 30 years following Heacox's wrestling match with the tuna he filled many of the most interesting fisheries posts in New York; fought frequently (and successfully) to protect threatened fishing waters; was ap- pointed district manager of the south fisheries region; and in his latter years of service became first secretary and then deputy commissioner of the New York Department of Conservation, where he experienced both the rewards and woes of an old field man in office. His comments about his "biopolitical" life and colleagues give hope that our form of state government may yet prove a boon, all appearances to the contrary.

In his closing pages Heacox reflects on the rejuvenating power of days spent out-of-doors, on the growing hostility to sportsmen now being shown by "activist antihunters," and on the paradox involved in his premise that true sportsmen-conservationists have done more to foster wildlife than all their detractors combined. As one whose meager possessions include a two-and-three-quarter-ounce Winston flyrod and a six-and-a-half-pound twelve-gauge Greener, I understand that paradox. The pity is how few of those who take to our woods and streams each year share even a fraction of Heacox's love and sense of responsibility for the game they pursue. If more did — or could be persuaded to — then the author's conviction that "outdoor recreation is an inherent right instead of a privilege" may continue to be valid. If not, then hunting and fishing will become in time the recreation of an ever diminishing, and privileged, few.

THE EDUCATIONOF AN OUTDOORSMANBy Cecil E. Heacox '26Winchester, 1976. 185 pp. $8.95

A recently retired senior pilot with Pan Am,Mr. Wood returns regularly to Hanover,whence he embarks with Bait and Bullet comrades on trout-fishing and grouse-hunting expeditions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

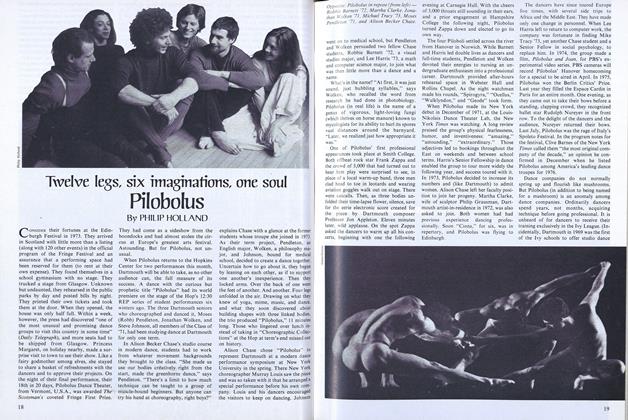

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

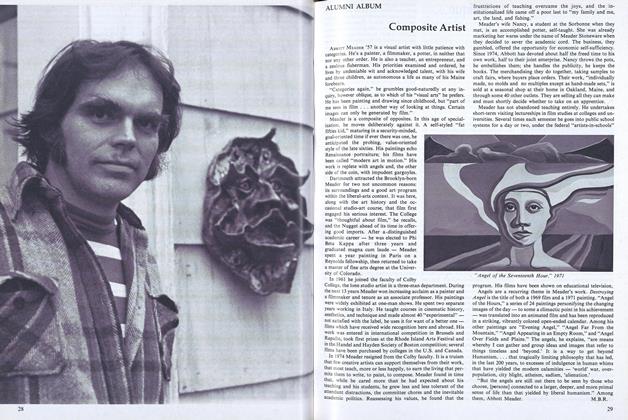

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

DECEMBER 1971 -

Books

BooksCOLLEGE PHYSICS

July 1960 By ALLEN L. KING -

Books

BooksTHE CATCH AND THE FEAST.

JANUARY 1970 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Books

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, VOL. 1: FOUNDATIONS OF AMERICAN LITERATURE,

January 1952 By H. G. R. -

Books

BooksSPEARHEADS FOR REFORM, THE SOCIAL SETTLEMENTS AND THE PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT 1890-1914.

JANUARY 1968 By PHILIP S. BENJAMIN