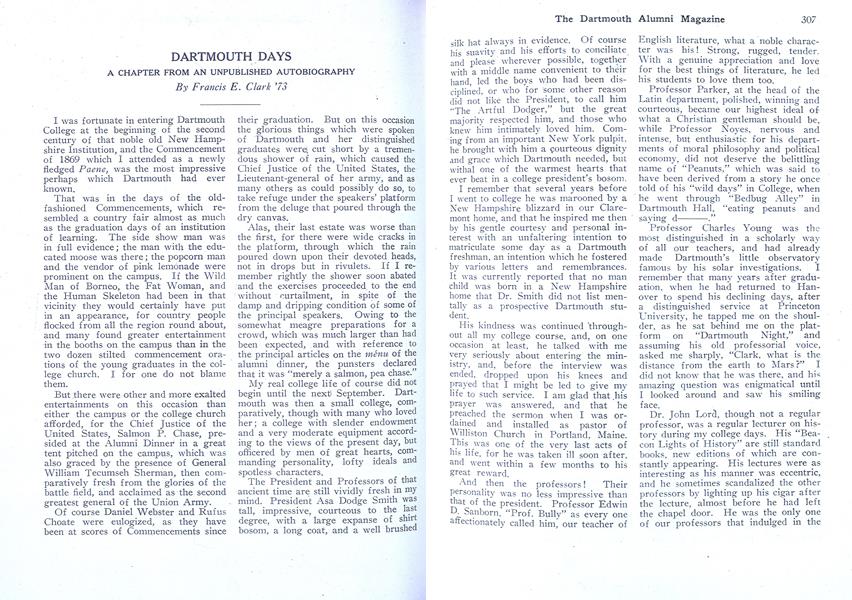

I was fortunate in entering Dartmouth College at the beginning of the second century of that noble old New Hampshire Institution, and the Commencement of 1869 which I attended as a newly fledged Paene, was the most impressive perhaps which Dartmouth had ever known.

That was in the days of the old-fashioned Commencements, which resembled a country fair almost as much as the graduation days of an institution of learning. The side show man was in full evidence; the man with the educated moose was there; the popcorn man and the vendor of pink lemonade were prominent on the campus. If the Wild Man of Borneo, the Fat Woman, and the Human Skeleton had been in that vicinity they would certainly have put in an appearance, for country people flocked from all the region round about, and many found greater entertainment in the booths on the campus than in the two dozen stilted commencement orations of the young graduates in the college church. I for one do not blame them.

But there were other and more exalted entertainments on this occasion than either the campus or the college church afforded, for the Chief Justice of the United States, Salmon P. Chase, presided at the Alumni Dinned in a great tent pitched on the campus, which was also graced by the presence of General William Tecumseh Sherman, then comparatively fresh from the glories of the battle field, and acclaimed as the second greatest general of the Union Army.

Of course Daniel Webster and Rufus Choate were eulogized, as they have been at scores of Commencements since their graduation. But on this occasion the glorious things which were spoken of Dartmouth and her distinguished graduates were, cut short by a tremendous shower of rain, which caused the Chief Justice of the United States, the Lieutenant-general of her army, and as many others as could possibly do so, to take refuge under the speakers' platform from the deluge that poured through the dry canvas.

Alas, their last estate was worse than the first, for there were wide cracks in the platform, through which the rain poured down upon their devoted heads, not in drops but in rivulets. If I remember rightly the shower soon abated and the exercises proceeded to the end without curtailment, in spite of the damp and dripping condition of some of the principal speakers. Owing to the somewhat meagre preparations for a crowd, which was much larger than had been expected, and with reference to the principal articles on the menu of the alumni dinner, the punsters declared that it was "merely a salmon, pea chase."

My real college life of course did not begin until the next September. Dartmouth was then a small college, comparatively, though with many who loved her; a college with slender endowment and a very moderate equipment according to the views of the present day, but officered by men of great hearts, commanding personality, lofty ideals and spotless characters.

The President and Professors of that ancient time are still vividly fresh in my mind. President Asa Dodge Smith was tall, impressive, courteous to the last degree, with a large expanse of shirt bosom, a long coat, and a well brushed silk hat always in evidence. Of course his suavity and his efforts to conciliate and please wherever possible, together with a middle name convenient to their hand, led the boys who had been disciplined, or who for some other reason did not' like the President, to call him "The Artful Dodger," but the great majority respected him,, and those who knew him intimately loved him. Coming from an important New York pulpit, he brought with him a courteous dignity and grace which Dartmouth needed, but withal one of the warmest hearts that ever beat in a college president's bosom.

I remember that several years before I went to college he was marooned by a New Hampshire blizzard in our Claremont home, and that he inspired me then by his gentle courtesy and personal interest with an unfaltering intention to matriculate some day as a Dartmouth freshman, an intention which he fostered by various letters and remembrances. It was currently reported that no man child was born in a New Hampshire home that Dr. Smith did not list mentally as a prospective Dartmouth student.

His kindness was continued throughout all my college course, and, on one occasion at least, he talked with me very seriously about entering the ministry, and, before the interview was ended, dropped upon his knees and prayed that I might be led to give my life to such service. I am glad that .his prayer was answered, and that he preached the sermon when I was ordained and installed as pastor of Williston Church in Portland, Maine. This was one of the very last acts of his life, for he was taken ill soon after, and went within a few months to his great reward.

And then the professors! Their personality was no less impressive than that of the president. Professor Edwin D. Sanborn. "Prof. Bully" as every one affectionately called him, our teacher of English literature, what a noble character was his! Strong, rugged, tender. With a genuine appreciation and love for the best things of literature, he led his students to love them too.

Professor Parker, at the head of the Latin department, polished, winning and courteous, became our highest ideal of what a Christian gentleman should be, while Professor Noyes, nervous and intense, but enthusiastic for his departments of moral philosophy and political economy, did not deserve the belittling name of "Peanuts," which was said to have been derived from a story he once told of his "wild days" in College, when he went through "Bedbug Alley" in Dartmouth Hall, "eating peanuts and saying d----."

Professor Charles Young was the most distinguished in a scholarly way of all our teachers, and had already made Dartmouth's little observatory famous by his solar investigations. I remember that many years after graduation, when he had returned to Hanover to spend his declining days, after a distinguished service at Princeton University, he tapped me on the shoulder, as he sat behind me on the platform on "Dartmouth Night," and assuming his old professorial voice, asked me sharply, "Clark, what is the distance from the earth to Mars?" I did not know that he was there, and his amazing question was enigmatical until I looked around and saw his smiling face.

Dr. John Lord, though not a regular professor, was a regular lecturer on history during my college days. His "Beacon Lights of History" are still standard books, new editions of which are constantly appearing. His lectures were as interesting as his manner was eccentric, and he sometimes scandalized the other professors by lighting up his cigar after the lecture, almost before he had left the chapel door. He was the only one of our professors that indulged in the weed, so far as I know, and that indulgence was laid to his general eccentricity, and was condoned on that score.

I remember hearing from an uncle of mine, who was also his college classmate, an amusing story concerning him, — how in a class prayer meeting he was called upon to offer prayer, all the students being upon their knees. Being somewhat nervous and excitable he hitched his chair from place to place, until, when he was through, he was on the opposite side of the room from the place where he began. In the mean time he had unconsciously tied his handkerchief round his knees, so that when all the others arose from their reverential posture, he was quite unable to do so until he was unbound.

Professor Proctor of the Greek chair, Professor Hitchcock, the eminent geologist, Professor Quimby who took us through the intricacies of conic sections and the differential calculus, and the younger men, Tutors Lord and Emerson and Chase, all deserve mention for each one had a personality that impressed itself upon the students.

Our class of '73, owing doubtless to the glories of the Centennial Year was the largest that had ever entered Dartmouth College, and numbered all told, with those who entered later in the course, and counting the men in the Chandler Scientific Department, (though they were not counted with the classicals in those days) fully 130 men, a very respectable number though scarcely a quarter of the size of the present Dartmouth classes.

There were rough and tough men in the college classes of those days, men who drank and swore and whose virtue was not immaculate. In spite of these men I am confident that the tone of the College as a whole was in those days earnest, sincere and genuinely religious. Those were the days of compulsory chapel and compulsory church which we took for granted, as we did the precession of the equinoxes. It never occurred to us that in a well-regulated college anything less could be demanded, while the class prayer meetings, though of course entirely voluntary were usually attended by fully half of . our class.

In the midst of our college course a genuine revival of religion occurred, as was usually the case in those days at least once in four years. Some of the strongest men intellectually and socially, in my class as well as in the other classes, were thoroughly converted. It can well be imagined how this revival rejoiced the heart of President Smith, a religious awakening in which he and his daughter Sarah and several members of the faculty took a prominent part in personal work for the students.

No Dartmouth students of my generation and of many that preceded and followed, for a generation of students is only four years in length, will forget Dr. Leeds, scholarly, solemn and uncompromising in the pulpit, but the very soul of geniality in his own home. This parsonage home and the homes of many of the professors were genuine havens of refuge in the limited social life of Hanover for all the students who would avail themselves of their privileges, and largely made up for the lack of other social attractions which city colleges are supposed to enjoy.

Freshmen fraternities, which have since been abolished, were then in vogue, and it was not until the beginning of my Sophomore year, according to the custom of that day, that I was initiated into the Zeta. Chapter of the Psi Upsilon fraternity, following in this respect in my adopted father's footsteps, for he was a charter member of the Zeta Chapter.

But those were modest days for college fraternities as for other college housings. We had no elaborate building with lounges and fireplaces and luxurious paraphernalia, but hired a modest room in the old Tontine. Yet the fraternity spirit in those days was most admirable. It was a rare and genuine fellowship that was promoted., and a clean sensible and serious view 01 lite as well while the extent of our convivialities was a banquet provided by a local caterer once a year.

But there was much time and thought put into our literary exercises which were held every week, and the debates and papers furnished almost the only opportunity for practice in speaking and composition. Among other happy memories I recall a visit to the Amherst Chapter as a Zeta delegate to the annual convention, and as----of the fraternity (how near I came to revealing an unrevealable secret!) I had much to do with the entertainment of the convention at Dartmouth the next year. This convention, like the previous one, passed off gloriously, though I remember that some of the brothers from the city colleges were inclined to turn up their noses at our country ways and country roads when we took them for a ride to the Shaker settlement at Enfield.

I am inclined to think that most college students today, whether from the country or city, would regard the surroundings of Dartmouth in the early seventies as exceedingly crude and primitive. We carried up our own water from the old-fashioned pump on the campus, and our own coal and wood from our private stock in the cellar. We chose our commissary and boarded in a so-called "club," making our bills of fare to suit our purses, few of which ever knew any superfluous cash. Dartmouth was then a poor man's college, and drew its constituency largely from the New Hampshire farms, with a considerable contingent from Massachusetts, and a sprinkling from the West. Dartmouth men then as now were famous for their loyalty to their AlmaMater, and for sending their sons back to the old College.

I may be allowed an old graduate's privilege, I am sure, to cherish the fond belief that quite as strong, vigorous and successful men were turned out in the days of the college pump and the kerosene lamp as in the modern times of shower baths and electricity.

I am tempted at this point to tell far more than my space will allow concerning my college mates and classmates, and as I think of Jack and Fred and Sam and Rich and Tom and Jim and Alf and George and Judge, and remember the distinguished lawyers and ministers and professors and college presidents who would have to answer if I called the roll today, I find that it would be quite impossible, within the limits of this volume, to tell what I would like concerning them. But these distinguished men were all there in embryo in that little New Hampshire village, and I could name scores who have made their mark upon their day and generation.

I was attacked by a genuine case of cacoethes scribendi, during my preparatory course at Meriden, and it became more virulent during the college days at Hanover. How well I remember my first published article! It appeared in the Manchester Mirror, a weekly paper, during my early Academy days, and related to the mysteries of Planchette, which was then exciting superstitious people and amusing saner ones. How I hugged that paper to my bosom! A volume of 500 pages would seem far less important now. But my pride took a tumble, as pride usually does, when I wrote to the editor and asked for payment for the article, and received his reply saying that he could buy any number of such articles for fifty cents apiece, and thought that the copy of the paper he had sent me was a quite : sufficient reward.

However, I was not entirely discouraged from hoping that I could sometime earn my living with my pen, and, during my college course, made various other essays in the same direction. A number of articles published in the OldCuriosity Shop, a Boston magazine of somewhat ephemeral life, brought me in over one hundred dollars, in the course of one year. I hope that my contributions did not hasten the death of the magazine, which expired the following season. These literary efforts, I suppose, were the cause of my election as one of the editors of The DartmouthMagazine during my senior year, ana also of a short-lived college weekly called The Anvil, which was started by a brilliant classmate, Fred Thayer, who afterwards served his apprenticeship on The Independent, and The New YorkTimes and whose untimely death was mourned by all.

My first book, entitled,. "Our Vacations," though it related largely to the excursions and outdoor life of college days, was not published until my Junior year in Andover Seminary. What wonderful excursions those were! Two weeks in the White Mountains, with half a dozen classmates at the close of Sophomore year, was a fortnight ever to be remembered. We walked from Hanover through the notches of the White Hills and the Franconias, while an old horse, and an impromptu prairie schooner which was just as good for the mountains as for the prairies, carried our tent, our blankets and our cooking kit. The yearly excursion of the newly fledged Juniors was a regular feature of those college days, and was perhaps the progenitor of the famous Outing Club which has helped to make Dartmouth the great outdoor college of the country.

I must not forget to record the unique experience of the Dartmouth men of the olden days as student pedagogues. Massachusetts in general, and Cape Cod in particular were quite overrun with college boys who were practising on the unsuspecting youths and maidens of the Old Bay State. Six weeks' vacation in mid-winter was the rule for Dartmouth in those days, while those who wished to teach were allowed six weeks more at the beginning of the spring term, which they were not obliged to make up. As a matter of fact, almost every boy either taught or told the faculty he "wanted to teach," so that Hanover was a particularly lonesome place during the three months from January to April. During my Freshman year I taught in Topsfield, Massachusetts, and in the Sophomore winter, in the adjoining town of Boxford, and during both of these winters had the privilege of living much of the time in the charming homes of two of my uncles who had married sisters of my mother, and were spending their declining years in Boxford, a town which enjoys the unique distinction of having, according to the past census, exactly the same number of inhabitants as in the days of the Revolutionary War.

The same winter that I taught in the first district of Boxford, where the classes ranged all the way from the a, b, abs, to the Beginners' algebra, "Sam" McCall, the present distinguished Governor of Massachusetts, taught in another district, and an eminent professor of New Testament Greek, Fred Bradley, (I give them their old-time names) in still another. Who imagined in those days that "Sam" and "Fred" would occupy these chairs ?

At the end of my Sophomore year, "the teaching privilege was taken away from Dartmouth students, or at least the winter vacation was cut short and all were obliged to make up for lost time, so that few were able to replenish their lean pocketbooks by the meager twelve-dollars-a-week salary for school teaching, and few Dartmouth boys thereafter made love to the Cape Cod maidens, or pitched the unruly big boys of their schools into the snowdrifts, an athletic feat for which they were frequently chosen in the earlier days.

While it would seem absurd today to take so much time out of a college course, I am not at all sure that those twelve weeks of teaching were not quite as valuable as any twelve weeks of being taught, and they at least enabled many a poor boy to finish his college course without too large a debt.

Our College was not visited by as great a number of distinguished men as at present, yet we had a course of lectures every winter, for those were the days when the "Lyceums" flourished, and the voice of the orator was heard in the land. Who was the lecturer among the coterie of Boston wits who declared that F-A-M-E spelt "Fifty And-My-Expenses ?" I am inclined to think that it was Edward Everett Hale, but I remember that when I had something to do with the College lecture course, he decided that one hundred dollars was about the right stipend for him. It seemed to us a large sum, but when he explained that he could earn as much by staying at 'home and writing articles we concluded that we must have him. "irregardless of expense." In those days we heard W. H. H. Murray, the brilliant meteor that flashed across the theological sky in Boston and soon went out in darkness. He gave us his tirade against "Deacons," with special reference to Park St. Church deacons. He was at that time also editor of The GoldenRule, and I little thought that I should follow him in the editorial office, and actually inherit the wooden chair with a collapsible writing table on which he wrote his sermons and editorials and Adirondack yarns. Theodore Tilton too, about the time of his memorable contest with Henry Ward Beecher, came to enlighten us about our political duties, and, if I remember rightly, he advised us to vote for Horace Greeley.

I remember, too, at one Commencement time, seeing the good-gray poet, Walt Whitman, clad in a blue flannel shirt open at the neck, shuffling down the main street of Hanover, where he had come to deliver a Commencement poem. His voice was muffled and I could not hear his poem and probably could not have understood it if I had heard it, but I remember that as I passed him on the street he gave me a gruff but hearty "Good morning."

My Psi U connections gave me the privilege of writing to the celebrated essayists, Brother E. P. Whipple, Brother Charles Dudley Warner, and others, asking for poems or addresses for convention days. I did not expect to get them, but it enabled me to secure some treasures for my autograph album. Charles Dudley Warner, I remember, whom I had modestly asked to write a poem to grace some occasion for his younger brethren, replied that he had never written a poem in his life and would have to decline "with thanks and tears."

While teaching school in Boxford. I remember driving one bitterly cold night to Lawrence to hear Wendell Phillips lecture on "The Lost Arts," a lecture which he gave some hundreds of times, and always with rare effect. I shall never forget that tall, graceful figure, surmounted by a splendidly symmetrical head, or that mellifluous voice, which was rarely raised above the conversational tone, but always conveyed his exact meaning with a nicety of expression, which the orator who tears passion to tatters, never knows.

Thus passed my college days, days which are always more likely to make an imperishable impression on a boy s memory than any others. For the benefit of a few old Dartmouth men, who may possibly honor me by reading these pages, I would say that I roomed, as some of them did," first in the Haynes house on Main street, then at Barney McCabe's where the library now stands, and for the last year in No. 10 Reed Hall, with its splendid outlook over Balch Hill.

How crude and unscientific the Dartmouth sports of those days would seem to a baseball fan and the football enthusiast of today! Baseball was just beginning to be reduced to Median and Persian laws, which, were supplanting the round ball and two old cat, of former days. Tennis was unknown, as well as basketball, and the football we played would today be considered a mere undisciplined scrimmage for the pigskin. Yet what rare fun was the old-fashioned football, when half a dozen fellows would get out on the campus and shout with 'stentorian lungs, "Whole divisions !

Whole divisions!" and the Seniors and Sophomores, the Juniors and Freshmen, would come streaming down from Dartmouth and Thornton and Wentworth and Reed, and line up against each other for a furious combat. After "the warning" the man who could most often, get the ball and do the most vigorous kicking was the best fellow. We never heard the mysterious numbers called out, or even knew the difference between a quarter-back and a half-back, but we were all in it, and no one thought of sitting on the bleachers while twenty-two men got all the exercise.

The annual cane rush might perhaps be counted among the athletic sports of the day, and one of my most vivid memories is that of the tall, dignified and portly form of President Smith, in spotless garments, getting into the midst of the fray, and shouting in classic phrase, "Disperse, young men, disperse to your rooms!" They finally dispersed, to be sure, after the Sophomores secured the fragments of the cane, but not until the worthy president had been hustled (without the least intention, of course) and his polished silk hat ruffled, I fear, beyond repair.

Those were rough old days in some respects, when the Freshmen's seats in chapel were once in a while drenched with a liberal supply of kerosene oil and occasionally a corpse from the dissecting room of the Medical school was set up in their seats to frighten the newcomers fresh from their guileless homes. We may congratulate ourselves that such "roughhousing" is a thing of the past.

In the late days of June, 1873, the seventy or more survivors of the Classical department of the Senior class were graduated, the Scientific students having a separate Commencement Day. The Commencement exercises were comparatively simple. We had no caps or gowns, but every Senior who could afford it, and there were few who could not, sported a tall hat, in memory, perhaps, of Daniel Webster. Nor were there any gorgeously arrayed trustees and distinguished alumni upon the platform, declaring by their fine-colored feathers whether they were M. A.'s or Ph. D.'s, D. D.'s, or LL. D.'s.

But the Commencement exercises always attracted a crowd, and each of the many speakers on the programme was assured of the sympathetic and often tearful attention of a father or mother, or perhaps a sweetheart in the gallery. The . red ribbon of the Phi Beta Kappa was not as great distinction, perhaps, in those days, for it was given to all in the first third of the class. Otherwise I might not be entitled to wear the key, though I graduated, if I remember rightly, Number 12 in the class.

The next day we separated, some to meet frequently, others occasionally at class reunions, and some never again in this life.