These facts, impressions and states of mind are set down during the first month since the United States' entrance into the Great War, that those who are interested, at a distance in place or time, may gain some knowledge of the war's effect upon an institution so vivid and sensitive as a great college. Information from other sources blocks out the true perspective.

Looking backward, one can see how natural the course of events in our nation has been.

No great moral conviction ever suddenly swayed a large and mixed group.

We have gone through nearly three years of "neutrality", during which, more and more, we have looked at one another and muttered, "Neutrality in such a cause is crime". We — some of us — have made vast sums of money out of the needs of those fighting our battles, and we — some of us — have been touched with shame doubtless more keen because we have not shared in the spoil. We have tried to quiet our uneasy consciences by academic criticism of the conduct of nations desperately striving for the last fragments of civilization against the marvellous organization of specialists in brute force. We have upheld the beauties of peace—peace which we all love and would see perpetualuntil we have been compelled to face squarely and answer the question, "Is anything worth more than peace?" Perhaps at times a deeper feeling of gratitude has come to us for the precious rights that our forerunners have bought for us with their blood, and we have at last caught a glimpse of that perplexing necessity in God's providence whereby humanity has had to fight its way up, and fight again to hold its place. We have wondered sometimes if it was true that,

"Our hearts grow cold, We lightly hold A right that brave men died to gain, The stake, the cord, The axe, the sword, Grim nurses at its birth of pain,"

and at the end a smooth-rolling, irresistible wave of duty has forced us, reluctant, to another ideal than that of ease. During this period of diffusion of moral ideas most of us have only grown a little older but—a very different matterthe boys of seventeen have become nearly twenty, and boys of twenty nearly twenty-three.

From the first it has seemed to us of only ordinary foresight that we were living on the thin crust of a volcano. These desperate nations had little time to be polite, and their wild struggles were sure to create cumulative irritation which would involve the innocent bystanding nation unless it turned and ran swiftly off the earth. And so the colleges, where every possibility is brought to examination, have been ready with keen or moderate enthusiasm to seek preparation for the dubious future and to insure against the impending storm. The young men have looked for guidance to the authorities of the college who in their turn have looked in vain to Congress or the War Department for modern methods not of the 19th century nor of the Spanish War, but of the swiftly producing minute. Thus in this and many other colleges, from lack of knowledge and resources, the best course has not been taken, and the students willing to be led have felt the hesitation and uncertainty and have waited, assuming more than their real indifference, with an occasional outburst of impatient criticism. And yet—I can speak from certain knowledge—with much seeking we did not know how best to go to work. Nor has the extensive publicity of many other institutions been convincing that the best was being done.

In the spring of 1915 we contributed our cash, handsomely as we thought to the field ambulances in France. A little group of pioneers, not wholly appreciated at the time, went to the American Ambulance service in the early summer. With the later splendid abundance of offering men it is well to recall these early Volunteers, - G. B. McClary, PD. Smith L. V. Tefft and Richard Hall. In the latter part of the college year 1915-1916 a home-drilled battalion had done all that could be expected without definite purpose and end in view and had fallen to pieces in a most natural way. The faculty had encouraged attendance at Plattsburg in the summer of 1916, and by scant majority had given dangerously "unacademic credit therefor.

Then came a pause, not of indifference, but of the deepest solicitude in view of the increasing gravity of the situation and of the signs of earnestness showing through the usual airy carelessness of the undergraduates.

What could the College do?

As the situation grew acute in the early months of 1917, the President of the College asked this question of a committee of college officers, and undergraduates of influence and discretion. A survey of all the possibilities of the time seemed to point, by exclusion, to a method newly marked out by the War Department in General Orders No. 48, consisting essentially of three hours a week of drill under an approved officer, with only the obligation of persistence to the end of the year. Enrollment was made rather slowly, just before the Easter recess, because detailed regulations could not be given in advance and because of the desire for greater activity.

Soon it appeared that the War Department was in no condition to furnish an officer.

At this time, in the last few days before the recess, an immediate call came for volunteers in the Naval Reserves for coast defense, and to this, with its promise of instant service, many responded. So came the recess to a college, quiet, not greatly excited, but inspired to say, "I must do something; what can I do best?"

On April 6th, in the middle of the Easter recess, Good Friday, in the Year of Our Lord 1917,— note the words— the President of the United States signed the Resolution of Congress declaring a state of war to exist. It was received all over the country with intense seriousness and little tumult and shouting.

As the College re-assembled it was plain that the period of doubt and questioning of the great issues was over. Action was in all minds. For a few days natural but ' not excessive excitement prevailed, and some fluttering for position. A few not knowing what to do left college, but wisely were sent back to wait for the best disposition of their abilities, and after a little settled down with the majority of the College to improve the time and bide the opportunity.

Others found their work and went to it.

For a little while mourners went about the streets and in subdued voices exaggerated the depletion of the College and their own hard lot in remaining. The silver cord was loosed and the golden bowl was broken. But the more: golden the bowl the less easy its fracture. It has been stated, that the cream of the College has gone; this is true if you are not too nice in following out the'figure. Much of the loose and detachable excellence of the College has floated away. But the cream of a college is a continuous product and not a limited component, and each whirl of the storm centrifugal will meet the new demand.

So the College has settled to a certain attitude of steadfast readiness. Outgoing trains daily bear away personal baggage, and one member of the College after another announces that he is going to his definite appointment; but there is no demoralization. Men are thoughtful and surprisingly steady.

When you consider it, the professional ways of college teachers are no more queer than those of other men. They only seem so because they cannot be expressed in the usual terms of dollars. How scandalous that money should flow through the hands of men of finance without interest or discount or toll as it passes! How bitter, how extreme in his ways is the conductor of a railway train upon which you would" ride without a ticket. How tiresomely engineers of various sorts fix their minds upon accuracy of measurements! How lawyer - like lawyers become! Likewise we college teachers wrestle agonizingly with the questions of how we can give credit for college work that is not done, or "pass" men who have not completed the course, or break academic continuity that has its roots in the very foundations of the world. So it was truly wonderful that with barely a questioning voice and with no dissenting vote we violated all these principles and released men to the service from April 14th, with full credit, and granted to students in residence substantial reduction in college work to enable all to engage in the 12-hours a week of drill.

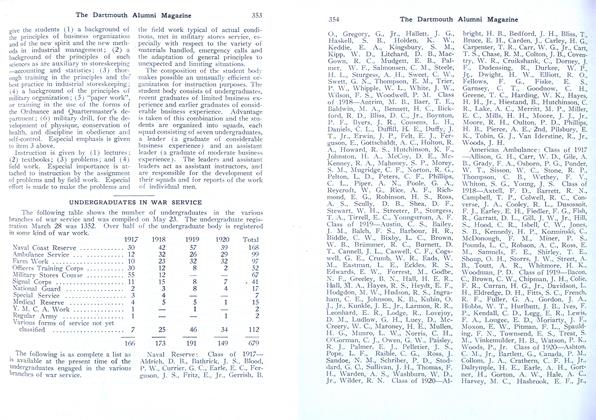

Practically every student has put himself in the way of prepared usefulness. Many have gone from the College into full service. The official list of these at the time of writing is 554, and a considerable number have not yet connected their enrollment with the College office. A record, as accurate as can be gathered, is growing daily in the Parkhurst Building, but a list merely of the forms of service into which the men have widely scattered can not fail to interest. For men of the College are now in the Naval Reserves, the National Guard, the Red Cross and American Ambulance Services in France, the Military Stores School, the Coast Guard, the Reserve Officers' Training Camps, Military Census and State Surveys, Organized Agriculture, Signal Service and Wireless Telegraphy, Aviation, and Y. M. C. A. work in prison camps abroad. Some, like the medical students, have realized that the best possible use they could make of their time was in the completion of the professional study of the year. A beautiful incident has been the setting forth on the 5th of May of 44 men for ambulance service in France and the splendidly appreciative farewell given them by the largest group of alumni ever socially assembled in New York, — a great contrast to the quiet departure, two years ago, of the four men of early vision. A band of equal number will probably sail on the 2d of June.

Going back a little,— during the recess it appeared after exhaustive attempts of President Hopkins to secure an officer from the regular army that the War Department had none to assign. An officer of experience and efficiency was, however, obtained from the Massachusetts National Guard and the whole plan of drill changed to real work of 12 hours or more a week; and a new enrollment included practically every student in residence for whom it was possible. The number at its highest stood at about 1100, but was diminished somewhat as men were called away to full service elsewhere.

Daily from 3 to 5 every man in College not prevented by other duties joins in serious drill, and already the regiment is making a most respectable appearance. One may, without captiousness and in the belief that the early .future should and will bring great changes, venture the opinion that it all has little more application to the conditions of 1917 warfare than the fabulous skill of the left-handed sons of Benjamin, who "could sling stones at an hair's breadth and not miss."

(The ink is hardly dry above, that is the writing machine has scarcely ceased its click, when a officer from the splendid Canadian force in France appears among us ready to teach some of the arts of modern warfare practiced today at the battle front. The obstacles and entanglements remaining in the afternoon are being cleared away for longer hours of soldiering, and if we cannot yet learn the delicate adjustments of modern artillery, or from the air, scout and photograph and charge ground forces with machine guns, or bring down the huge birds with vertical fire, we can dig ourselves into trenches and perhaps defend them or rehearse the battle charge, and when it is over have a bath.

And under another officer, of the United States, a real signal corps of sixteen enlisted men is in vigorous daily wig-wag practice.)

But the drill does teach to obey orders, puts potential energy into motion, opens an arbitrary approach to the elaborate mechanics of modern field conditions, and is the best discipline now to be had. The effect of its daily arduousness upon the morale of the College is admirable. Without any farcical element or the latent taint of easy evasion it makes men up-headed and alert as no amount of languid cheering from the bleachers between mouthfuls of peanuts and hot dog could ever make them.

And if you have a strange feeling in the throat and a tendency to moisture in the eyes as you think of the possible destinations of all this fine material it is no shame. But choke and wink it back. Mother did raise her boy to be a soldier. And the boy would think you very funny to shed tears. It may be sad; but how much more sad, how desperate for the world if the most advantaged youth did not respond in such a time of crisis! Blood-drenched Europe, those whose language we inherit and those who are heroically pressing the barbarian from their homes have long turned wistful eyes towards us and wondered that we could not see our duty as it looked to them. The words of H. G. Wells as late as the current year seem now to find their justification, ''Every country is a mixture of many strands. There is a Base America, there is a Dull America, there is an Ideal and an Heroic America. And I am convinced that at present Europe underrates and misjudges the possibilities of the latter."

If we were to take the pulse of Elanover today we should find it calm and Steady. Its color is a little flushed in a healthy way as the countless flags wave from stores, dwellings and fraternity houses. The great tidal wave that on selected days sweeps from the Oval,— motor cars, hasty workers, green caps, unhurried but decided food-seekers, leisurely dames and their escorts — is missing because all extra-mural competitions are canceled, partly from a sense of fitness and partly from necessity caused by departures and the lapsing of rivals. It is somewhat replaced by the khaki hosts that flow and ebb at 3 and 5. The College is proceeding in comfort and peace without organized musical and dramatic clubs, though a laudable band may be discovered by listening. And by wise yielding to the inevitable, the Junior Prom has been given up. Its genial hospitality would keenly feel the absences, and however subdued its plan might be, the presence of the sisters and the cousins and those neither sisters nor cousins means entertainment. By causes about which I offer no philosophy the fraternities have been disproportionately bereft of their members. From the few neighborhood inquiries it appears that 83%, 66%, 66%, 59% of the active membership of those answering have gone to serve the country in some of the ways already mentioned.

The College is not at all suffering from lack of exercise; but to keep the baseball hand in, games are played between the different companies of the regiment, and eleven men are detached from each of two companies daily and bid go to it.

Outside of student life there is a marked tendency to usefulness. A company from the faculty and village — a homeguard — drills evenings. And in the highly organized State no less than eleven of the faculty are on the Committee of Public .Safety and its sub-committees, several in high degree assiduous and useful. Three are on committees of the National Security League. Public-spirited citizens outside the College are doing their part. The spirit of intensive agriculture is pervading the place. Two blades of grass have little chance to grow where only one grew before, but the newly ploughed acres where never grew a potato or a bean now give hope of food, already sorely needed if the prices are evidence of need.

Indeed from the anxiety "to do something," from the eager and-not-to-bechecked overlapping of organizations, of societies, of national, state and local committees odd questions of efficiency arise. Suppose that all the organizations that have caused Professor X to set down upon a card what he was willing or thought himself competent to do were to call upon him for those services ? It is one of the problems of early organization which will gradually settle itself and certainly not by the way of loss of services.

The work of the women has been and continues highly organized, large, persistent and valuable. From the beginning of the war in Europe a branch of the Canadian Red Cross has been most industrious and" productive, seconded, only a little later, by the French Emergency Fund. The Soldiers' Comforts Club came into activity last winter. And now that need threatens our own forces the American Red Cross is preparing to meet it with the same energy in rooms hospitably furnished by the Young Men's Club. And into the organization of the State has been brought a capable local Food Committee primarily concerned with methods of conservation.

The intimacy and closeness of it all is deeply impressive, the individual threads run so directly from the home to the camp. It is to be expected, in a college, at a time like this that interesting young men known for months or even years, should speak of their plans and go, or perhaps, none the less missed, disappear quietly from sight. One does not wonder that scores of parents telegraph, or write or come to discover the meaning and the soundness of decisions suddenly disclosed by sons who for the first time have formed independent purposes.

But it is difficult to realize that boys known in their homes from birth have scattered,— to France, to the army, to the many varied purposes of a country at war: that a neighbor and colleague is ordered to be in instant readiness for call; that a son is commissioned and only waiting for orders; that five nephews, according to their qualifications are already in service; that a well-trained niece is on her way across the water with a corps of Red Cross nurses ; but these are the conditions that with slight variations repeat themselves with us all and give a nearness and a reality to a status which the mind is very slow to accept as genuine.

Great opportunities have come to ours, but one shrinks a little from the revelations of the coming months pr years even though the major part of the soul may be fixed in the courage and determination that the cause demands.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATES IN WAR SERVICE

June 1917 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1917 By Sturgis Pishon -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

June 1917 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE NAVAL RESERVE

June 1917 By Edwin Parker Hayden '16 -

Article

ArticleTHE TRAINING SCHOOL FOR MILITARY STORES SERVICE

June 1917 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1915

June 1917 By Leo M. Folan

Article

-

Article

ArticleDistinguished Lawyer

March 1943 -

Article

ArticleV-12 Associated School

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleNuptials

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleYE SPORTE OF HOUSE-PARTIES

DECEMBER 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleTRIBUTES TO TWO PROMINENT ALUMNI

February 1916 By JOSEPH AREND DEBOER -

Article

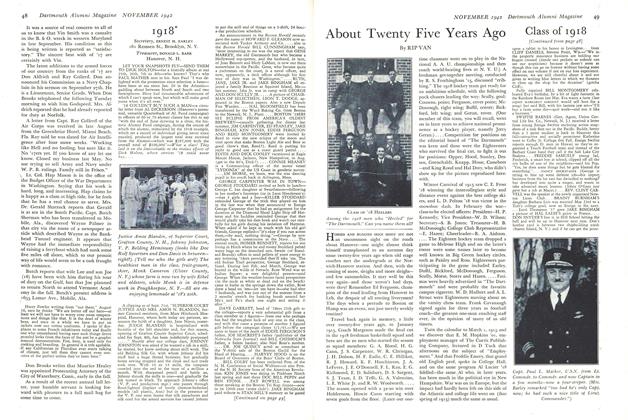

ArticleAbout Twenty Five Years Ago

November 1942 By RIP VAN