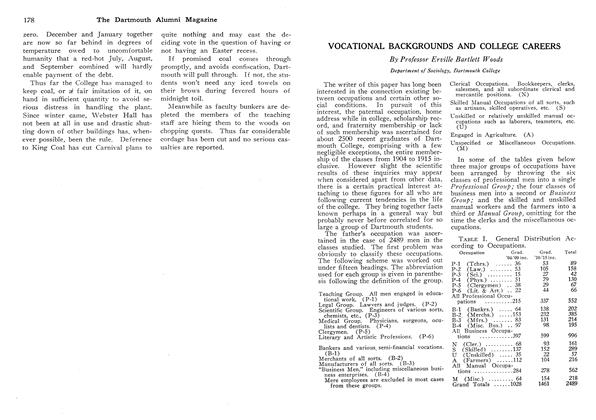

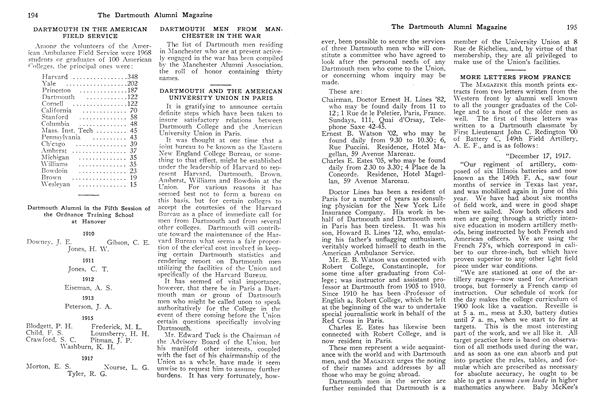

background of Dartmouth students develops some interesting facts and suggests a multitude of questions. As Dartmouth's facilities for doing things adequately have increased and improved,— notably perhaps the physical facilities,— the College has drawn more and more largely from the business class of the nation. For ten years past more than one-third of the student body has consisted of the sons of bankers, merchants and manufacturers. Of the professions, that of law, which has the closest business affiliations, is most largely represented. Indeed the sons of lawyers and business men constituted a good half of the student body from 1906 to 1911: and there is no reason to believe that, of late, there has been any considerable change in the proportion.

The first clear inference to be drawn from this is that the outward aspect and inward procedure of Dartmouth are such as to commend themselves to practical folk. This is probably the case. Location, plant and method of doing things are attractive, orderly and pretty thoroughly free from nonsense. If one has a dollar to spend he can probably get more for it at Dartmouth than anywhere else.

It is the pressure of a business class, prospering with prosperous times, that has necessitated the newer dormitories, fireproof in construction, steam heated, electric lighted, carefully sanitated; not luxurious or pretentious, but thoroughly safe, comfortable and homelike. And, in turn, such adequate housing has increasingly attracted the attention of parents anxious that their children "should have the best within reason. Add to this — in the usual order of parental interest — the excellence of the faculty and of the curriculum, together with the beneficent shadow of the Tuck School, and it develops in the natural sequence of events that the sons of business men have become the majority of the student body and have, on the whole, assumed domination of the student life.

That this domination makes for entirely satisfactory results to these men, or to others, seems a matter of doubt. The fraternities and all that fraternity affiliations mean in the social satisfactions of the college course are mainly theirs. Theirs, too, is probably the growing tendency toward fraternity segregation which is beginning to be observable. As a result, while the dominant group is gaining at Dartmouth the advantage of geographical variety in its association, it is failing to gain the more important advantage of class, or better, occupational variety. The situation further is one that carries no cure of its own. As the sons of men in certain vocations,— notably those whose emolument does not increase with rising prices, — find themselves increasingly at a disadvantage numerically and socially thev will increasingly tend to turn elsewhere for their education. And thereby Dartmouth will lose both in its intellectuality and in the richness of its student life and experience.

Lest we become excited at this point it must be remembered that Professor Woods' figures indicate merely a tendency and not a settled condition. Of the colleges and universities of the east which have grown of late the same thing is doubtless true. But the time to deal with a difficulty is while it is in the incipient stage.

In the present instance a number of remedies suggest themselves: first of all that of reducing the scale of operations, and hence the cost of living at Dartmouth. It is doubtful that this could be done. The difference between the cost of living today and that of thirty years ago is the difference between electricity and smudgy oil lamps, between the Hanover reservoir and the infected campus pump, between Massachusetts Row and "bedbug alley." Who would go back to them at any price ? A more practical suggestion lies in the increase of scholarship funds for the encouragement of able but impecunious boys to come to Dartmouth. Certainly this is advisable and necessary, but it does not offer any strong counteraction to observable tendencies. If the poor man is more likely than not to fail of social opportunity once arrived in College, he is not likely to be a happy or effectivemember of the body studious.

And talking about it, or lecturing about it will not do any good. The validity of the preachment may be granted: but it will produce no results in conduct.

If there is any remedy, it probably lies in administrative measures directed toward the greater concentration of student life to the end of ensuring the closer contact of all types of men. The first requisite for this lies, without doubt, in limitation of numbers. That is something quite likely to take care of itself for some time to come; but, as normal ways of life return, almost certain to demand full consideration as a policy.

Another requisite lies in the devising of means for bringing the student body as a whole, or in large groups, into intimate relationships. When President of Princeton, Woodrow Wilson sought to accomplish this very end by the establishment of a number of small living colleges or quadrangles. Harvard is trying the costly experiment of separate freshman dormitories. Thus far, Dartmouth has done nothing beyond limiting the number of occupants of fraternity houses. In view of the location of this College, a special dormitory system for any class seems unnecessary; but the tendency toward segregation which, under the tutelage of upperclassmen, the freshmen ;early exhibit might well be offset "by the requirement of eating together ; coupled, perhaps, with the development of College Hall as a freshman lounge and club. It would be desirable, too, if, after being given free rein during their second and third college years, seniors might be brought together cummens a (in Commons) for the last months of their course.

These are artificial devices, it must be admitted; but artificial devices are necessary. Human beings are, after all, shy and suspicious. They move in narrow circles. As a whole, they shun new experiences and unwonted contacts. The sham barriers -which they erect to differentiate themselves from others, seem to them real and insurmountable until circumstance destroys them. The circumstance may be calamity that tears down the barriers and brings men together for what they are; or it may be some consciously adopted discipline, a moral equivalent of calamity, accepted because it bids fair to enforce those intimacies of association out of which grows the understanding of true human values which is fundamental to democracy.

Editorially the Boston Herald thinks that the colleges are not awake to the situation. They are not straining their energies to the utmost in co-operative movements for avoiding duplication of effort; nor are they speeding up in the production of graduates whom an eager government is anxious to receive a year earlier than the time usually appointed. And The Herald further quotes the authority of President McCracken of Lehigh as favoring a federal administration to pool all college facilities and operate the institutions as a unit.

This last suggestion should not be lost. If the federal government will guarantee to foot the bills, it is a fair bet that there will be some lively scrambling of trustees eager to repose their academic burdens on the broad bosom of Uncle Sam and of any renowned coal operator whom he may appoint as his immediate representative on the job.

If, with characteristic obtuseness, the government fails at once to seize its opportunity in the field of education, there is one quite obvious piece of economy that could be effected by mutual agreement. Dartmouth's enrollment is down about forty per cent. If Williams and Amherst are in the same situation, there ought to be nothing in the editorial to prevent the two of them from shutting up shop and sending their students to Hanover. This would bring Dartmouth's quota up to normal, would enable the College to proceed under full steam, and would release from the sister colleges a number of teachers for employment in necessary production. The more any Dartmouth man contemplates this idea, the more business-like and satisfactory he is sure to find its simplicity, efficiency and perfect avoidance of duplicate effort.

But The Herald has a plan for keeping all the colleges full without recourse to absorptive methods of co-operation. It would have the New England institutions, at any rate, admit, without further test, any and every high school graduate who would accept the invitation, and then would keep the curriculum buzzing twelve months on end to turn him out a finished product in three years instead of four.

When the other proposals are so full of inspiration, it seems ungracious to criticize this, one; but honesty compels. Somewhere a link or two seems to have dropped out of its logic. Even a reasonably uncloistered brand of educator would find difficulty in perceiving why youngsters probably unfit for experiments with higher education in time of peace should be encouraged to try them, at the cost of clamoring field and factory, in time of war.

It looks, too, as if there might be a fallacy in the notion that anything is to be gained by hastening graduation by means of a continuous session. An institution suitably located and favorably equipped with certain kinds of apparatus can assuredly make itself useful by offering intensive technical courses of short duration and frequent repetition, without considerations of calendar. But, as things stand today, the "culture colleges" are having quite sufficient trouble to hold their students in leash until June. And they will congratulate themselves if they are able to re-open in October with a registration at all comparable even to the reduced figures of 1917.

A householder is usually wide awake while a burglar holds a revolver against his head and arranges the looting of his dwelling. It is no argument against him that he fails, under the circumstances, to achieve anything very brilliant or very striking. The colleges are in a somewhat similar situation. The war has seized them by the throat, depleted their faculties, carried off their students, put one foot on their assets and used the other to raise their expenses beyond immediate recall. If, at this psychological moment, some hero will crawl through the window and handcuff the war, his intervention will be highly appreciated. Pending such rescue, the colleges may be forgiven if they do the best they can to avoid untimely demise as a result of premature effort in the way of making a disturbance.

A fine, yet rare, attribute in a man is the willingness to be useful at whatever task may present itself, with an eye more to the usefulness than to the task. Thomas Browne McGuire, formerly of the class of 1917, had that attribute. His plan was to join the country's aviation forces, and he was in his home city, Chicago,, waiting appointment. When the recent blizzard struck the city, clogged its thoroughfares, and paralyzed transportation vitally necessary to the nation, the call came for volunteer shovelers on the railways. McGuire did not stop to worry over the fact that he was booked to be a flier. He turned to with a shovel on the tracks of the Northwestern. There, heavily muffled against storm and cold, he failed to hear the onrush of a train released from its snow bondage. He was struck and killed. Death might have found him in the clouds above the fields of France, but no more bravely and honorably doing his bit than, shovel in hand, a volunteer workman among the snow drifts of Chicago.

This month the alumni may count upon being notified pretty explicitly of what is expected of them toward boosting the Dartmouth War Fund, for such will be the entitlement of the Alumni Fund this year. Organization for the work is pretty nearly, but not quite, completed. As usual, the unit of operation will be the class. Later classes will, in so far as may be, have each its agent. In addition to this, each of the five councilor districts has been divided and subdivided so as to offer local organizations whose function it will be to assist class agents in ensuring communication with all of their constituents.

The appeal of the War Fund has already manifested itself. Following the distribution of last month's ALUMNI MAGAZINE there came one check from a friend of the College, and another check issued by the United States Treasury. It was the travel allowance of a young Dartmouth man in the service. He wrote that he expected soon to sail for France and wanted to do his bit for the College before going. So he had made over his government check, probably the first he had received, and for an amount more than twice the average called for.

The alumni of the Great Divide had a meeting a few weeks since and, contrary to sacred traditions against talking money matters at a dinner, they organized there and then to insure a showing for the War Fund. The Great Divide did well last year. The report for that period, presently to be sent out, puts it pretty near the top from the standpoint of averages, while New England, all things considered, makes the poorest showing of any district.

This year we shall see what we shall see; but New England will have to do considerable hustling if it is not to be humbled by more distant, less accessible and less populous districts.

Those who think that all the phenomena of the good old days have gone with the good old days themselves are invited to rejoice in a real old-fashioned winter. And this year the lucky man has been the primitive citizen who uses kerosene lamps, heats and cooks with wood derived from his own wood-lot, and has no plumbing in the house to freeze solid as a preliminary to bursting.

At the College heating plant outdoor temperatures are recorded six times in twenty-four hours, at four, eight, and twelve o'clock. The coldest day of the gleeful holiday season averaged 24 degrees below zero. On that day the plant consumed close to forty-one tons of coal in keeping the buildings only above the danger point. For the days from December 26 to January 4, inclusive, the average was 8 degrees below zero. December and January together are now so far behind in degrees of temperature owed to uncomfortable humanity that a red-hot July, August, and September combined will hardly enable payment of the debt.

Thus far the College has managed to keep coal, or a! fair imitation of it, on hand in sufficient quantity to avoid serious distress in handling the plant. Since winter came, Webster Hall has not been at all in use and drastic shutting down of other buildings has, when ever possible, been the rule. Deference to King Coal has cut Carnival plans to quite nothing and may cast the de ciding vote in the question of having or not having an Easter recess.

If promised coal comes through promptly, and avoids confiscation, Dartmouth will pull through. If not, the students won't need any iced towels on their brows during fevered hours of midnight toil.

Meanwhile as faculty bunkers are depleted the members of the teaching staff are hieing them to the woods on chopping quests. Thus far considerable cordage has been cut and no serious casualties are reported.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleVOCATIONAL BACKGROUNDS AND COLLEGE CAREERS

February 1918 By Erville Bartlett Woods -

Article

ArticleMORE LETTERS FROM FRANCE

February 1918 -

Books

BooksA Bishop's Message

February 1918 By J. L. M. -

Article

ArticleTHE INTERCOLLEGIATE INTELLIGENCE BUREAU IN 1918

February 1918 By William McClellan -

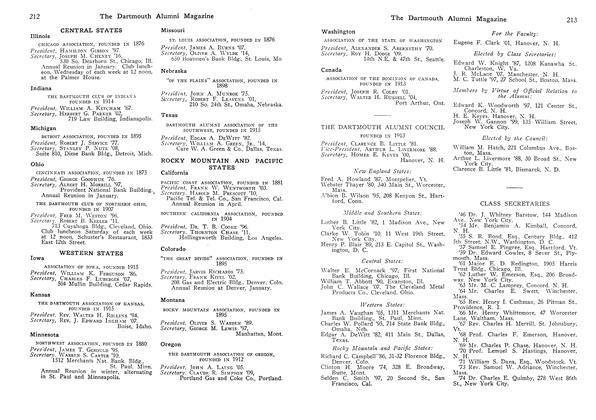

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

February 1918