The writer of this paper has long been interested in the connection existing between occupations and certain other social conditions. In pursuit of this interest, the paternal occupation, home address while in college, scholarship record, and fraternity membership or lack of such membership was ascertained for about 2500 recent graduates of Dartmouth College, comprising with a few negligible exceptions, the entire membership of the classes from 1904 to 1915 inclusive. However slight the scientific results of these inquiries may appear when considered apart from other data, there is a certain practical interest attaching to these figures for all who are following current tendencies in the life of the college. They bring together facts known perhaps in a general way but probably never before correlated for large a group of Dartmouth students.

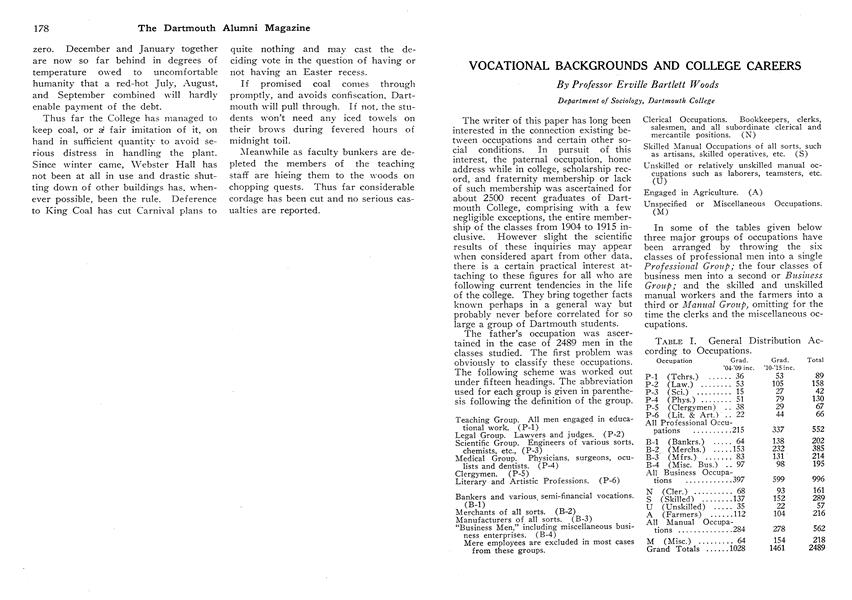

The father's occupation was ascertained in the case of 2489 men in the classes studied. The first problem was obviously to classify these occupations. The following scheme was worked out under fifteen headings. The abbreviation used for each group is given in parenthesis following the definition of the group.

Teaching Group. All men engaged in educational work. (P-1) Legal Group. Lawyers and judges. (P-2) Scientific Group. Engineers of various sorts, chemists, etc., (P-3) Medical Group. Physicians, surgeons, oculists and dentists. (P-4) Clergymen. (P-5) Literary and Artistic Professions. (P-6) Bankers and various, semi-financial vocations. (B-l) Merchants of all sorts. (B-2) Manufacturers of all sorts. (B-3) "Business Men," including miscellaneous business enterprises. (B-4) Mere employees are excluded in most cases from these groups. Clerical Occupations. Bookkeepers, clerks, salesmen, and all subordinate clerical and mercantile positions'. (N) Skilled Manual Occupations of all sorts, such as artisans, skilled operatives, etc. (S) Unskilled or relatively unskilled manual occupations such as laborers, teamsters, etc. (U) Engaged in Agriculture. (A) Unspecified or Miscellaneous Occupations. (M)

In some of the tables given below three major groups of occupations have been arranged by throwing the six classes of professional men into a single Professional Group; the four classes of business men into a second or BusinessGroup; and the skilled and unskilled manual workers and the farmers into a third or Manual Group, omitting for the time the clerks and the miscellaneous occupations.

TABLE I. General Distribution According to Occupations.

Occupation Grad. Grad. Total '04-'09 inc. '10-'15 inc. P-1 (Tchrs.) ...................... 36 53 89 P-2 (Law.)......................... 53 105 158 P-3 (Sci. )........................ 15 27 42 P-4 (Phys.)........................ 51 79 130 P-5 (Clergymen) ................... 38 29 67 P-6 (Lit. & Art.) ................. 22 44 66 All Professional Occupations....... 215 337 552 B-1 (Bankrs.)...................... 64 138 202 B-2„ (Merchs.) .................... 153 232 385 B-3 (Mfrs.) ....................... 83 131 214 B-4 (Misc. Bus.) .................. 97 98 195 All Business Occupations........... 397 599 996 N (Cler.).......................... 68 93 161 S (Skilled) ....................... 137 152 289 U (Unskilled) ..................... 35 22 57 A (Farmers) ....................... 112 104 216 All Manual Occupations............. 284 278 562 M (Misc.).......................... 64 154 218 Grand Totals....................... 1028 1461 2489

If the classes studied are divided into two groups of six classes each, it becomes evident at once that students from some of the occupational classes are increasing very much more rapidly than those from others; in the table which follows a comparison is made between the earlier period from 1904 to 1909 and the later period which embraces the classes from 1910 to 1915 inclusive. For convenience of comparison the numbers are reduced to a common base of 100 for each group included in the table.

TABLE 11. Number graduating during 1910-1915 per each 100 graduating during the previous six years—(1905-09). Arranged in the order of increase:

For every 100 grad- Per cent uating 1904-09, there of graduated 1910-15 the Increase number entered be- or low: Decrease Unskilled Manual Occupations.................. 63 —37 Clergymen................... ..................76 —24 Farmers........................................93 — 7 Skilled Manual Occupations.............. ......111 +11 Clerical Occupations...........................137 +37 All Occupations................................142 +42 Business Men...................................151 +51 Professional Men exclusive of Clergymen.................................. 174 +74

From this table it appears that the graduation of the sons of unskilled workmen, of ministers and of farmers was less in the second six-year period than in the first; that the graduation of sons of skilled workmen increased about a fourth as much as the growth of the college (11% as against 42%) ; that the sons of clerks about kept pace with the growth of the college; and that the sons of business and professional men increased during the second six-year period about 50% and 75% respectively. (See also Appendix — Table IX.)

The sons of clergymen show such a divergence from the sons of other professional men that in several of the tables, in spite of the fact that the group is a small one, they are entered separately.

In regard to scholarship, one method of comparison is to ascertain the average (median) grade earned by each of these vocational groups for the whole four years of the college course.

TABLE III. Scholarship Record for entire college course according to vocational groupings:

Rank Occupational Groups Median Grade 1 Clergymen's Sons.................77 2 Sons of Farmers..................74 3 Sons of Skilled Manual Workmen.73 3 Sons of Unskilled Manual Workers 73 5 Sons of Clerical Employees.......72 5 Sons of Professional Men other than Clergymen ....................72 7 Sons of Business Men ............71

It will be noted in connection with the above table that the four highest groups in point of scholarship are precisely the four groups which are failing to keep up in numbers with the growth of the college as shown in the previous table.

In Table IV which follows, a comparison of a somewhat different sort is made of a half dozen typical groups, two drawn from the professional occupations, two from the business occupations, and two from the manual occupations. 288 sons of lawyers and doctors, 416 sons of bankers and manufacturers (B-1 and B-3), and 505 sons of artisans and farmers (S and A) are included in this table. For the sake of clearness the figures have been reduced to a percentage basis.

TABLE IV. Percentage of high and low scholarship in selected vocational groups:

Men of Low Scholarship (50-69 inc.) Men of Fair Scholarship (70-79 inc.) Men of High Scholarship (80-100 inc.) Totals % % % % Sons of Lawyers and Doctors 41 39 20 100 Sons of Bankers & Manufacturers 45 39 16 100 Sons of Artisans and Farmers 33 44 23 100

It appears from the above that the artisans and farmers send us only about three-fourths as many low-grade men in proportion to their numbers as do the bankers and manufacturers, but they send us nearly one and a half times as many high-grade men as do the bankers and manufacturers. The sons of lawyers and physicians appear to occupy an intermediate position. Selection doubtless plays a part in the explanation of the high scholarship of manual workers' sons.

in making this study it seemed that some attention should be given to the question of membership in fraternities. The study of fraternity membership is based on data for 2288 graduates whose affiliations were found recorded in the college annuals published by the classes with which they graduated. This total consists of 1427 fraternity men and 861 non-fraternity men. In Table V the scholarship rank of each of the seven groups shown in Table III is given also for Fraternity Men Only and for NonFraternity Men Only.

TABLE V. Scholarship record by vocational groupings:

WHOLE GROUP STUDIED AS IN TABLE III Ranfc Occupational Group Median Grade 1 Clergymen's Sons................ 77 2 Sons of Farmers................. 74 3 Sons of Skilled Manual Workers.. 73 3 Sons of Unskilled Manual Workers 73 5 Sons of Clerical Employees...... 72 5 Sons of Professional Men other than Clergymen.................... 72 7 Sons of Business Men............ 71

FRATERNITY MEN ONLY 1 Clergymen's Sons.................77 2 Sons of Farmers..................72 3 Sons of Skilled Manual Workers ..71 3 Sons of Professional Men other than Clergymen.................... 71 5 Sons of Clerical Employees ......70 5 Sons of Business Men ............70 7 Sons of Unskilled Manual Workers (20 men only)..................... 69

NON-FRATERNITY MEN ONLY 1 Sons of Clerical Employees................ 77 1 Sons of Unskilled "Manual Workers .........77 3 Clergymen's Sons.......................... 76 3 Sons of Professional Men other than Clergymen...............................76 5 Sons of Farmers........................... 75 5 Sons of Skilled Manual Workers ............75 7 Sons of Business Men.......................73½

In the above table the difference between groups may not appear large enough to have great significance, yet when we divide each vocational group into its fraternity and non-fraternity constituents, we find several interesting things. In the first place it is evident that the sons of business men rank a little lower whether in fraternities or out of them than either the sons of professional men or manual workers.; the only group which made a lower average was the 20 sons of unskilled manual workers who were admitted to fraternities. The fact that the sons of the unskilled in fraternities averaged 69, the lowest in the list and that the sons of the unskilled outside of fraternities stood first in the non-fraternity list leads to speculation as to what principle of selection is at work here. The principal factors of selection for college in America at the present time appear to be financial ability, personal force, intellectual promise and athletic ability; all possible combinations of these factors are found of course. With regard to the Unskilled group referred to above, it is possible that a number who were marked mainly by athletic ability or by personal force "made" a fraternity, while another group of relatively high scholarship but lacking athletic prowess or any unusual personal force or charm as well as financial ability were not admitted to fraternities. With the exception of clergymen's sons the non-fraternity contingent of each vocational group did from three to eight points better work than the fraternity contingent; clergymen's sons, however, averaged one point better in fraternities than out of them. Finally, the purpose of Table V is simply to show the extent to which the differences in scholarship between the vocational groups are connected with the differences in scholarship between fraternity and non-fraternity men. Inasmuch as a majority of some of the vocational groups are found in the fraternities, while a majority of the membership of other vocational groups are outside of the fraternities it is possible that the scholarship records of the various vocational groups are different from one another for several distinct reasons, among which differences in their social life while in college should not be overlooked. In order that the matter may be made as clear as possible, the extent of these differences in fraternity membership should be noted. The following table contains data on this point.

TABLE VI. Percentage of vocational groups who are members of fraternities:

% Misc. Business Men 78.2 Bankers, etc. 77.4 Lawyers 76.3 (All Business Men ............71.6) Manufacturers 70.6 Teachers 68.6 (All Professional Men ........66.4) Merchants 65.8 Physicians 65.2 Literary Men, etc. 63.3 Engineers, etc. 62.8 Clerks 61.9 Clergymen 45.7 Skilled Manual Workers 45.0 (All Manual Workers......... 40.4) Unskilled Man. Workers 37.7 Farmers 35.0

If we compare the above with the data in Table II we note that the four classes making the lowest percentages of admissions to fraternities are precisely the four groups which in point of numbers are falling behind the general growth of the college; it will also be remembered from Table III that these are the four groups which lead all others in scholarship.

It is obvious that the vocational distribution is related in some degree to the distribution of geographical sections. Table VII presents the vocational distribution of three groups of graduates, those coming from the immediate locality, i.e., N.H., and Vt., those coming from Massachusetts, and those from distant sections, i.e., south or west of Pennsylvania, or from beyond our national boundaries. These limits were selected arbitrarily with the intention of presenting a fair picture of the immediate constituency of the college, of the state from which our largest contingent comes, and of the extensive region 400 or 500 miles or more distant from the college.

TABLE VII. Geographical sections from which graduates were drawn, by vocational groupings:

Distant N. H. & Vt. Mass. Sections % % % Professional Class 19 20 32 Business Class 32 40 53 Manual Class 35 22 5 Cleical & Misc. 14 18 10 100 100 100

It might be added that the men from New Hampshire and Vermont numbered 697, the men from Massachusetts, 1005, while those from distant sections numbered 351. It appears from this table that this immediate region has sent to the college about equal numbers of business men's sons and manual workers' sons, and about half as many professional men's sons as manual workers' sons; Massachusetts has sent about equal numbers of professional mens' sons and manual workers' sons, and about twice as many business men's sons; thus far the proportions are fairly even, but when we turn to the distant sections, we find that they send six times as many professional men's sons as manual workers' sons, and ten times as many business men's sons. The continued increase in the number of students coming from considerable distances will therefore, in the absence of counteracting influences, tend to still further accentuate the disproportionate increase of the sons of professional and business men.

It is a fair presumption that students who are able to travel considerable distances to and from college have, on the average, larger financial resources than those coming from shorter distances. This may be connected with the fact shown in the following table that membership in fraternities seems to vary directly with the distance from which the student comes.

TABLE VIII. Percentage of vocational groups from different geographical sections admitted to fraternities:

All Distant N H. & Vt. Sections Sections % % % Sons of Prof'l Men 02 66 75 Sons of Bus. Men 66 72 80 Sons of Man. Wrkrs. 35 40 47

The men from distant sections appear from this table to join fraternities in from 12% to 14% larger numbers than do the men of the same occupational classes who come from the immediate vicinity of the college.

CONCLUSIONS

Social statistics are often open to a variety of interpretations and the writer would prefer for the most part to leave the work of interpretation to others. The following four propositions are, however, put forward as tentative conclusions:

1. The sons of manual workers make a slightly better record for scholarship than do the sons of business and professional men, with the exception of the sons of clergymen. This may be partly, but is by no means wholly, the result of fewer fraternity affiliations on the part of the sons of manual workers.

2. The expansion of the constituency of the college over a wider geographical area has been accompanied by a contraction of that constituency into a narrower range of occupational and hence social classes. Thus the college tends, apparently, to become more and more representative of the country geographically, but less and less representative of the whole industrial and social fabric of the country.

3. It is probable that this change also involves some loss of intellectual ability, inasmuch as the sons of farmers and other manual workers, constitute a small delegation, so to speak, from a very large occuDational class not ordinarily sent to college unless some affirmative reason clearly exists for so doing. The business and professional classes, on the contrary, out of their somewhat larger incomes and in pursuit of their more sophisticated ambitions, more often send their sons to college as a matter of course without any clear affirmative reason existing in the mental character of the sons themselves. This difference in selection may, indeed, be slight, but that it operates 'in some degree can hardly be doubted.

4. Democracy implies the ability to think of men as essentially comrades whatever their lot or station; it is easy for men of the same type to develop democratic attitudes, but it becomes difficult as the types diverge. Whenever the college, therefore, can sweep within the magic of her own unifying spirit the most diverse elements from city and country, from among the sons of the toilers and the sons of the leaders, she is enabled not only to develop a very significant democracy within her own walls, but to set forward that costlier democracy in state and nation which the American people are now agonizing to achieve.

Appendix — Table IX. Present Freshman class compared with groups of recent graduates in regard to fathers' occupations:

Grads. Grads. Fresh. 1904-09 1910-15 1921 % % % Sons of Prof'l Men 20.9 23.0 25.4 Sons of Bus. Men 38.6 40.9 45.2 Manual W'krs' Sons 27.6 19.0 11.8 Sons of Clerks & Misc. Workers 12.8 16.9 17.4 100 100 100

Here is revealed a consistent and rather extraordinary shrinkage in the number of the sons of manual workers; among the graduates of 1904-09 they were almost half as numerous as the sons of business and professional men, in the classes of 1910-15 they were less than a third as numerous, while in the entering Freshman class which will graduate in 1921 they are exactly a sixth as numerous as the sons of business and professional men.

*Note: The small size of this group precludes any satisfactory statistical treatment of it.

Professor Erville Bartlett WoodsDepartment of Sociology, Dartmouth College

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Woods' study of the vocational

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleMORE LETTERS FROM FRANCE

February 1918 -

Books

BooksA Bishop's Message

February 1918 By J. L. M. -

Article

ArticleTHE INTERCOLLEGIATE INTELLIGENCE BUREAU IN 1918

February 1918 By William McClellan -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

February 1918

Erville Bartlett Woods

Article

-

Article

ArticleDRAMATIC ASSOCIATION

July 1920 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Night

January 1936 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Services for Dartmouth Menin Service

October 1943 -

Article

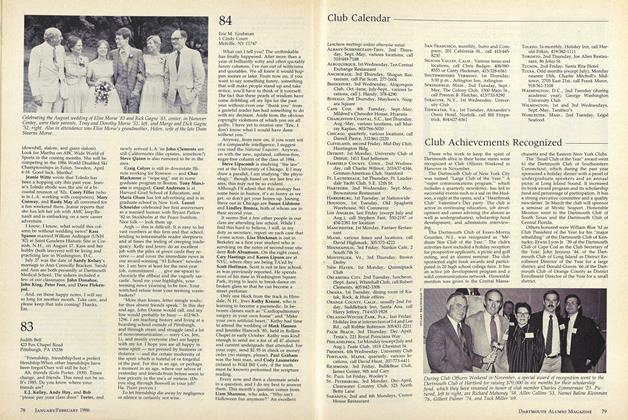

ArticleClub Achievements Recognized

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 -

Article

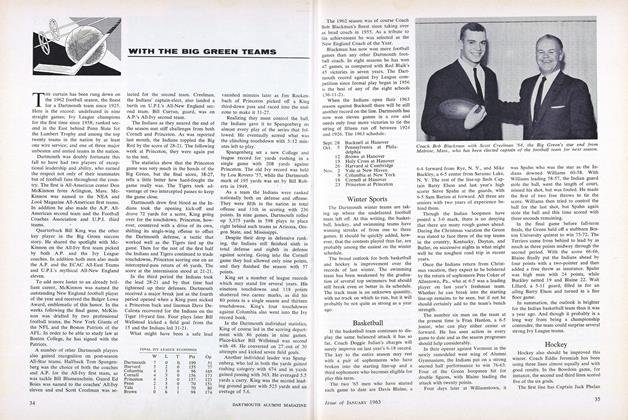

ArticleBasketball

JANUARY 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleA Decade of Dartmouth on Moosilauke

January, 1930 By Robert Scott Monahan