in the Levant", expresses the judgment of a level-headed and unprejudiced person who has lived enough in the lands of which he writes and has associated intimately enough with their peoples to have absorbed—rather than consciously studied and intellectually analyzed— their point of view. His is not the cleverly achieved opinion of a backstairs journalist piecing together policies from fragments of diplomatic gossip, and surmise, but the honest reflection of one who has encountered representative men of the Near East in relationships best calculated to reveal their deepest feelings ; namely, those concerned with the up-bringing and long-time welfare of their children.

The decision of the faculty to make changes in the entrance requirements of the College so as to offer a greater degree of elasticity than now exists, is probably less epoch-making than appears on the surface and than some of the discussion about it has implied. Certain things a student should have wrestled with and conquered before being admitted to Dartmouth College. They should be the things calculated to afford a secure foundation upon which to build a cultural superstructure—whatever, with changing times, that may mean. The number of them is probably less important than the thoroughness of their subjugation, the curse of college preparation being not so much insufficient quantity as pervasive sloppiness of method.

Yet for this the preparatory schools have been able to offer at least a good excuse. Indeed, instead of accepting a defensive position in the matter, it has, of late, been making pretty consistent attack on the college for insisting upon the pursuit of preparatory studies quite unrelated to modern life. What is good enough byway of making a youngster ready, as his years permit, to tackle the job of being a citizen and a wage earner ought to be good enough byway of preparing him for college, which, after all, aims only still more highly to develop his potentialities of leadership in these very things. Thus argues the school, not without justice.

Perhaps the misunderstanding is due to rather hazy notions of collegiate functions. To the preparatory school a college is a college and every youth, muddle minded or keen, gifted with mechanical genius or blest with a lyric soul is entitled to a college education and, more particularly to the inestimable benefits of a college degree. And the colleges, having accepted a pseudo scientific notion of standardization, have failed to observe that there is one specification for silk thread and yet another for motor axles. The educational efficiency of the future will probable correct this. Differences in the function of different institutions will tend to be more clearly recognized when that time arrives. College entrance examinations will aim at an objective determination of type and vigor of mind, rather than at an appraisal of its undigested content. Until then it makes very little difference what, beyond an irreducible minimum, college entrance requirements consist in. But the rigor of their application will be important.

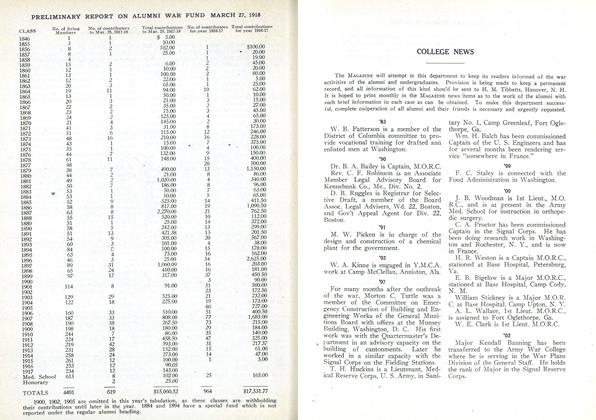

Elsewhere is printed a report of the Dartmouth War Fund to date. Three classes hold their subscriptions until later in the year, 1900, 1902, 1905, and are not to be estimated. Much the same is true of '84 and '94. For the rest the figures are accurate within a few days. The total is encouraging; the average excellent, and the number of givers pitiful.

And it is the number of givers now that is quite as important as the amount given. If some great donor were to come along and offer to shoulder the burden of the moment—an unimaginable event—his generosity should be diverted to some other need of the College. For two things are at stake now: the immediate progress of the College, and its justification for being. If it can not justify itself, its immediate progress is of no particular consequence. The general situation is just about this: The student body, normally 1500 strong, has shrunk to 850. In consequence, five dormitories are closed with a resultant reduction in annual net income of $20,000. The reduction in tuition fees will prove to be close to $70,000. Other reductions will bring the College revenues a total loss of close to $100,000. This the trustees faced last June as the probable deficit for the coming year. They accepted it as the alternative to such disorganization of the teaching and administrative force as would threaten the usefulness of Dartmouth for years to come.

There has been some query as to whether the College has been practising economies calculated to offset the losses in income. If there had been previous extravagance, economy might more easily now be featured. Yet measures taken will save close to $40,000 of the $100,000 loss. A number of the faculty have gone into government service, or have accepted positions in other institutions. Their places are not being filled. The men who remain are doing their work.

Maintenance is being kept at a minimum cost despite increasing prices. A coal bill normally $25,000 will, this year, amount to $40,000. The difference may be offset in part by deferring, even to the danger point, various repairs and improvements. Webster Hall, whose heating is always an item of expense, has not been opened during the entire winter. The various departments of instruction, too, are restricting their requirements and even the buying of books for the library, always too small, has been curtailed.

The upshot will be a war deficit estimated, today, at $60,000 for the year. Even if the money could well be borrowed to meet it, the policy of accepting such a cumulative burden would be little short of suicidal. It would mean Dartmouth's emergence from the war period bound and gagged against undertaking new measures of usefulness to meet new conditions of national life and thought.

This makes the alternative pretty clear. Either the College must contract at all points until its educational life becomes no more than a feeble trickle, or it must look to outside sources to maintain an infused vitality. This last is the purpose of the Dartmouth War Fund.

The Fund comes before the alumni not as a demand or as a request, but as an offered opportunity. If any body understands the College, they do. They are the ones in position to know and to care whether its work is really worth doing. Has Dartmouth meant enough in their lives so that in spite of world calamity, they want others to enjoy a similar experience ? Or are its present struggle and future fate a matter, in their estimation, of indifference or, at best, of minor importance?

There is only one way to make answer, and that is through giving or not giving to the War Fund. The need for the year is $60,000, an average of $10 for each of 6000 living alumni. If it is not met by gifts from the major part of that number the indictment of the College is a serious one. It can take little pride to itself in the service which its graduates are rendering elsewhere if they, in their turn, recognize no obligation to the College as an inspiring influence whose power should, even at considerable sacrifice to them, be maintained. That is about all there is to it. The College is on trial with the alumni as judge, jury and advocate.

As to the verdict there seems no reasonable ground for doubt. The bounds are set already. The oldest class unit —that of 1846 is represented by 100 per cent. That means one man, in his ninety-second year, who wrote his check with his own hand and with it a letter of good cheer and pleasant reminiscence. The youngest class, that of 1917, hasn't yet reached 100 .per cent, but there is something almost equalling it in the letter of one man, a private in the National Army. He sent five dollars and with it a note saying: "It is a mere drop, but I hope to arrange an allotment or something that I may send five dollars regularly every month. I fully realize the seriousness of Dartmouth's situation and am anxious to furnish what little relief I can." That from a man on $30 a month pay. Since the first letter, he has sent another with another five dollar order. "The allotment," he says, "was refused, and I will have to attend to sending it myself."

Somehow it is the men in the service who are the quickest to respond. The first check for the Fund this fall was from a 1916 man; his travel pay, a United States Treasury check endorsed promptly to the Fund. And there are parents whose boys are on the other side. "My boy," says the mother of a non-graduate in Montana, "is flying in Italy. I enclose a check in his name. So, too, a father whose son is with the army in France, and another whose two sons are in Syria.

So it proceeds. The Class of 1864 was 100 per cent represented last year. It will be again this, and with a larger total. Out of the 'Bo's have come already three checks of $1000 each, and more promised. There are as many hundreds as formerly tens. A man in 1900 who is supporting his class endowment fund sends a special check with the message, "The only way I can get this out f my mind is to send you a check." Such is the spirit of those who have given, The quality of it should prove contagious. The year's end, it may be predicted, will bring to the College more than the money needed to clear it of debt. For really beyond money is morale, the confidence of those in Hanover that the work of education to which they have dedicated themselves, unhonored and unsung though it may be, is yet justified by tangible evidences of faith.

Those who recall the early meetings of the Class Secretaries must feel greatly pleased with the progress which the Association, founded by them, has made. It is not merely that there has developed an orderly method of procedure, and a constantly magnified sense of responsibility on the part of the secretaries for the fulfilment of their class duties. The notable fact is the growing exactness of understanding, by these representative alumni, of the real work of the College. They are interested in its educational policy, in the fulfilment of its educational mission, and in the solution of the problems which are involved. They have passed from the earlier attitude of cordially interested investigators to that of eagerly responsive helpers. Never was this so evident as at the recent meeting, here-following fully reported. A diminished attendance had been looked upon as a matter of course. The number present was, however, unusually large, and the accomplishment of transaction unusually serious and important. It is a hopeful indication.

Shall reunion classes reune at Commencement? Some are sure that they want to; some are still uncertain. The College hopes for a goodly representation of returning alumni. This puts some secretaries in a difficult position. They hesitate to organize a failure, they hesitate equally to destroy a hope. Under the circumstances the best advice seems to be to invite reunion, to prepare for such gathering as may present itself, particularly by insuring, if possible, a reasonable nucleus; but to undertake no elaborate program of entertainment.

Those who come with their wives are pretty sure to be more comfortably accommodated than usual. The family aspect of a Commencement seems therefore likely to enjoy a renewed impulse. The College will endeavor to provide sufficient employment to keep time from hanging heavily on idle hands.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleAMERICANISM IN THE LEVANT

April 1918 By Ernest Bradlee Watson '02 -

Article

ArticleTWO LETTERS FROM THE FRONT

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF LIEUTENANT EADIE '18

April 1918 By FRANK N. HUME -

Article

ArticleNOTES

April 1918